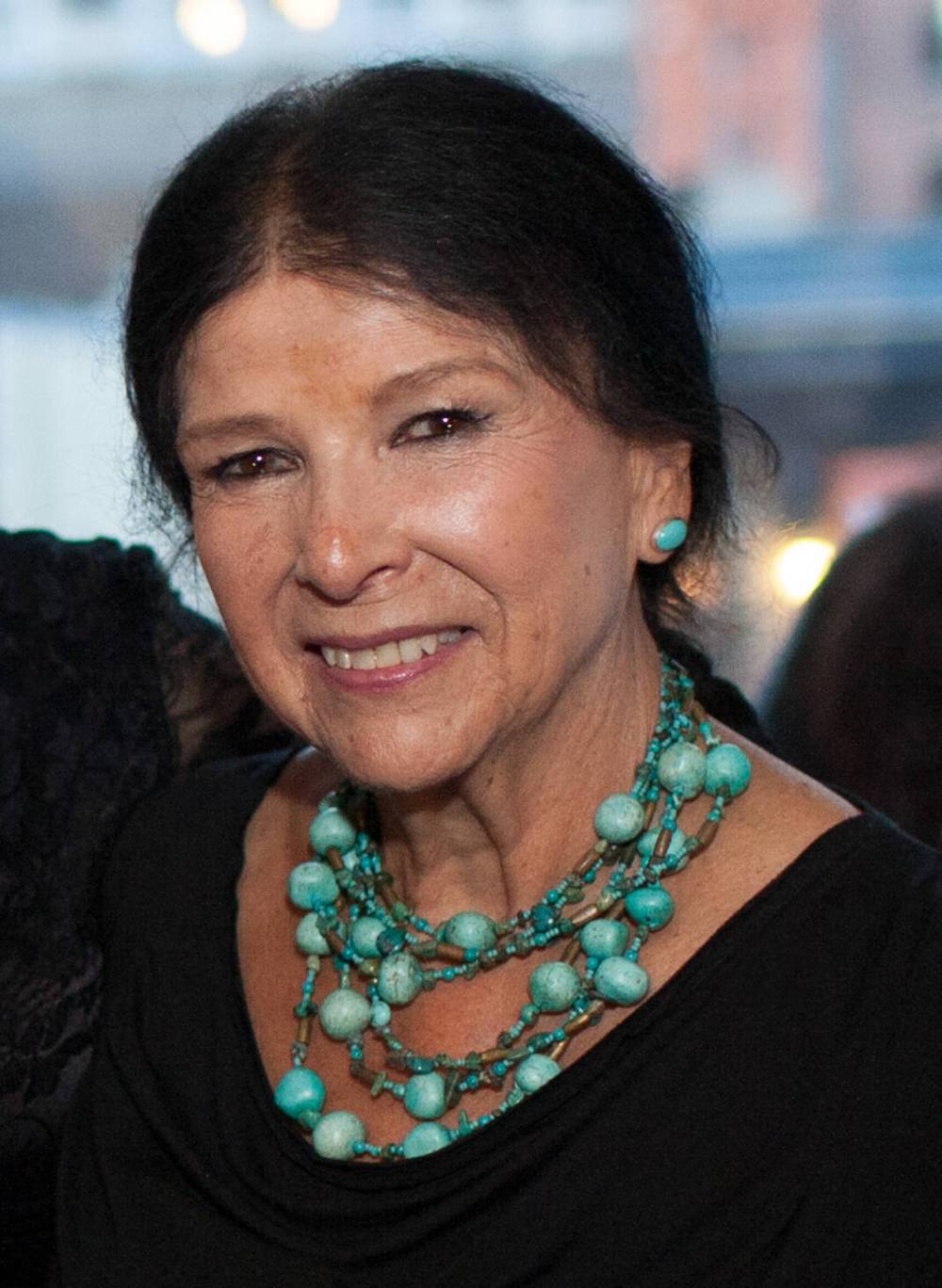

Sharing her stories APTN celebrates ‘mother of Indigenous filmmaking’ with 11 Alanis Obomsawin documentaries now streaming on demand

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/12/2021 (864 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Education has always been the goal for filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin.

In her experience, however, a proper education requires a revised curriculum.

“I was really in a big war against the educational system,” says the 89-year-old Abenaki director over the phone from her home in Quebec. “I felt that children had to hear a different story, because the books that they were using to teach were designed and, really, programmed to create hate towards Indigenous nations in Canada.”

Originally a singer, Obomsawin has been making documentaries about Indigenous perspectives, realities and issues with the National Film Board of Canada for the last 54 years.

She has created more than 50 films to date (and is still “very busy” making new work) about everything from the Oka Crisis to treaty relations to the child-welfare system.

Her 2021 film, Honour to Senator Murray Sinclair, made the Canada’s Top 10 list at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival. A selection of her vast catalogue is now available on APTN lumi, the broadcaster’s in-house streaming service.

“It’s wonderful; I’m so happy,” Obomsawin says of the partnership. “It brings more of our people to be in connection with all of these documentaries that are important to all of them.”

Lumi has been available to viewers in Canada since 2019 and offers on-demand, Indigenous-focused programming.

“Part of what we’re trying to do with that platform is to really celebrate the storytellers we have in our community,” says Lisa Ducharme, APTN’s director of online content. “Alanis Obomsawin, being kind of the mother of Indigenous filmmaking, is someone that we wanted to kick off that opportunity with.”

The collection includes 11 films created over a 35-year span. The earliest work, Incident at Restigouche, released in 1984, covers the Quebec police raids carried out to impose restrictions on Mi’kmaq salmon fishers, while the most recent, Jordan River Anderson, The Messenger (2019), chronicles the life and political health-care battle of the young boy from Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba who inspired Jordan’s Principle.

“The matters that she explores throughout all of her films are definitely relevant today,” Ducharme says. “From fishing to land rights to water and residential schools, these are still things that our communities face today, so being able to look at that from a historical perspective is important.”

Obomsawin agrees. She hopes viewers “learn the history, the real history, of this country,” she says. “It’s very new that people have the respect and the interest they have now… and they’re all shocked. They say, ‘How come we didn’t hear about this?’ Well, we talked a lot about it, but nobody was listening.”

Her first attempts at educating the public were through song. As a folk musician, she shared traditional Abenaki songs and performed at festivals and concerts in support of humanitarian causes across the world.

Filmmaking fell into her lap in the 1960s, after staff from the National Film Board noticed Obomsawin in a CBC documentary. She was hired as a consultant and later started creating educational films for classrooms.

“I hardly ever went to see films,” Obomsawin says, adding that while it took time to learn the equipment, she immediately saw potential in the medium.

“Very rarely did our people have a voice; there was always outside people telling about them. So, that’s when I started fighting for change and telling (the film board) that our people have a voice and can speak and they’re clever and they have all kinds of cultures and languages that are incredible.”

Throughout her career, Obomsawin has made a point of recording films in multiple languages: English, French and the language of the people featured in them.

While the industry has changed significantly — filmstrips are no longer the standard and there are more Indigenous people working in and creating content for film and television — her approach has never wavered.

“I will always do sound-only first. I don’t go in there with a crew camera and all that. I come by myself, alone with a tape recorder, and I interview people privately until I feel that I understand what’s going on,” she says. “The best thing you can give, if you’re making a documentary on somebody or a community, is time.”

Though many of the issues explored in her early work remain relevant today, Obomsawin feels hopeful about the future.

“I think we’re getting to a better place; we’ve never been there before,” she says. “I’m not saying that everything is perfect — that wouldn’t be true, we still have a lot of fights in front of us — but there is now, a condition and a place for us that wasn’t there before and it’s really from the goodwill and good people that exist everywhere.”

Visit watchaptnlumi.ca for subscription information and to access Obomsawin’s featured film collection.

eva.wasney@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @evawasney