Trained for the trauma The work has evolved over nearly three decades, but HSC's sexual assault nursing team ensures support and treatment available; rural health providers adopting some elements in effort to provide better care

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/06/2018 (2128 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Beth Ariss saw the women as they came in.

As a nurse in the emergency department at Health Sciences Centre in the 1980s, Ariss was often on shift, observing what invariably followed triage.

A patient would come in with a heart attack or some sort of trauma, and the lone doctor — there was often just one in the early hours of the morning — would have to make a choice. Examine the sexual assault patient, which would likely take several hours, or attend to the cardiac patient who might die without care?

“It’s no fault against physicians,” Ariss says nearly three decades later, just a reality of a busy ER.

“The priority is the cardiac patient, not the sexual assault. They’re always put lower,” she says. “There were a lot of emotional injuries and the trauma of the assault, but nothing that was usually life-threatening.”

How to get better care for those who have been sexually assaulted is a question Ariss deliberated over.

The answer came from Minneapolis, an American city that, in the late 1980s, had a sexual assault nurses program. Ariss and a few of her nursing colleagues went to visit. Those Minneapolis nurses were trained to operate at the intersection of health care and the legal system, trained to medically examine their patients and to make sure the evidence gathered would hold up if the case went to court.

The Winnipeg nurses decided to bring the idea home. Although the HSC sexual assault program became the first of its kind in Canada when it opened its doors in the 1990s, it didn’t always receive the institutional backing it does now.

Five nurses, Ariss included, helmed the program, voluntarily being on unpaid call so that one of them could respond whenever a sexual assault victim arrived at the ER.

They did the work in addition to their regular shifts, sometimes — more frequently at the start — incurring the frustration of their colleagues when they would duck out to do a sexual assault exam.

“It was a roller-coaster,” Ariss says. “We just kept having to fight, everything we wanted to go through, everything we wanted to get done.”

It would be years before the nurses were paid for being on call. But support for the program grew. You can see that shift in institutional support well beyond HSC, says Rosemarie Gjerek, who assumed responsibility for Klinic’s sexual assault program in 2000.

Across the province, she says, you’ll find more organizations dedicating additional resources to making sure they’re actually meeting people’s needs. At the same time, there are more community-led initiatives stepping up to offer support. More and more they’re finding ways to work together (HSC’s program connects patients with Klinic’s supports).

Gjerek attributes it not just to increasing awareness and education, but also to growing comfort in dealing with people who have experienced sexual violence.

“A trauma-informed perspective is critical in terms of providing services,” she says. “Systems that are becoming more adept and acknowledging those kinds of things are then a safe place for people to come and be heard and be believed and be supported.”

Creating safe places for care closer to home is something the regional health authorities have been working on for a while now. In a province where Shared Health was deemed necessary to build planning unity and service cohesion among regions mostly accustomed to operating in their own silos, the RHAs came together of their own volition a few years ago to form a sexual assault working group.

“They did quite a bit of research,” says Dr. Denis Fortier, chief medical officer with Southern Health. “They came up with some good protocols and some good ideas.”

Those recommendations are now in stasis, awaiting provincial evaluation. There is recognition that access to post-sexual assault care varies by ER across the province, says a spokeswoman for Manitoba Health, and she notes making that care more equitable will be part of Shared Health’s examination of emergency department services. But, there is no precise timeline.

In the meantime, Fortier says Southern Health is “a bit in a holding pattern” as the region waits for Shared Health to find its footing. But elsewhere across the province, some regions are still pushing ahead.

● ● ●

Every year, the Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners at Health Sciences Centre see hundreds of people. The vast majority of them are women and girls, although the program does accept men and boys, as well as trans men, trans women, and those who are non-binary. In the 2017-18 fiscal year, the hospital’s SANE nurses saw their largest volume of patients yet: 514.

The only constant with such a caseload is that every one is different, says Ashley Smith, one of two nurse co-ordinators and, as of last December, Manitoba’s only forensic nurse.

“I can honestly say with every single case I’ve had, even if I think maybe there are going to be similarities… there aren’t,” she says. Smith, who is a psychiatric nurse by training in addition to a forensic nurse and a SANE nurse, has worked for HSC’s sexual assault program since 2008. She became a program co-ordinator in 2012.

It’s hard to speak about her perceptions from a decade ago, but Smith says she likely shared the perception most outside of the field would have of someone who was sexually assaulted looking and acting a certain way. That they don’t has been the real eye-opener.

“Nobody reacts or responds the same way,” she says, and “People might choose different treatment for different reasons.”

The SANE team is called in for sexual assault cases disclosed in in-patient units or after the fact to staff members as well as for those who present in the child or adult emergency room (there were 154 children between the ages of zero and 17 treated in 2017-18, compared with 357 people who were 18 or older).

In the ER, the person has either disclosed they’ve been sexually assaulted or have given staff reason to believe they’ve been sexually assaulted. If it’s the latter, Smith says the SANE nurses are always “very honest” and will clearly say they’ve been called because sexual assault is suspected.

A cornerstone of the program is choice.

“Control’s really important after a sexual assault,” Smith says. “It’s the type of crime where control is being completely taken away from that person, which is why it’s a really important part in their healing journey to start giving them that control back as soon as you can.”

That starts with what care the person wants from the SANE nurses. While a full exam often averages between three and four hours, that’s not what everybody asks for. Sometimes they just want to be tested for STDs and given any necessary medications. Sometimes they want the police to be involved while other times they just want information about what support services are available to them (authorities must be informed when children are involved).

Since 2004, these conversations and exams happen behind a nondescript hospital door that is deliberately unmarked so as to preserve patient privacy. Before then, Ariss says, nurses would just find a private room wherever there was space.

Thanks to the determined advocacy of the program’s director at the time, the SANE nurses finally got their own dedicated space.

“It’s beautiful,” Ariss says.

You can see people change when they’re brought into the suite, Smith says.

It has soft-coloured walls adorned with paintings, medical supplies are kept in a wooden dresser, and music plays gently in the background.

“Usually you notice a visible change,” she says, “sometimes in their demeanour and how they’re feeling when we walk through these doors.”

The HSC program is considered the leader in sexual assault care in the province, says Carol Legare, director of patient services for adult emergency at HSC, which includes its sexual assault program.

“Lots of the other regions look to this, our SANE program, as what would be everybody’s ideal,” Legare says. “They look to us and ask, ‘How do you do this? How do you do that?’”

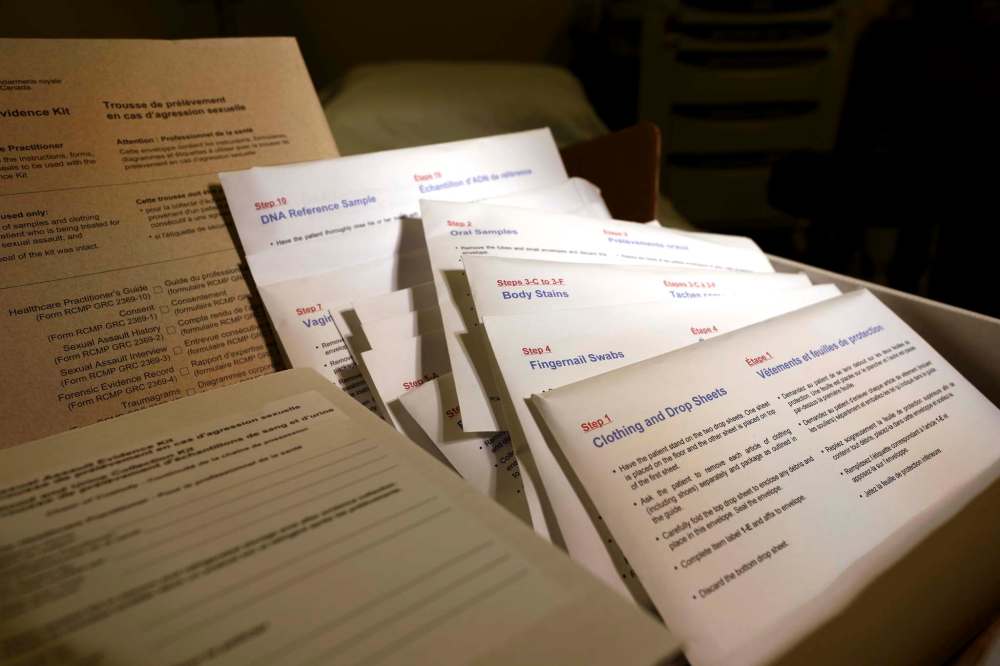

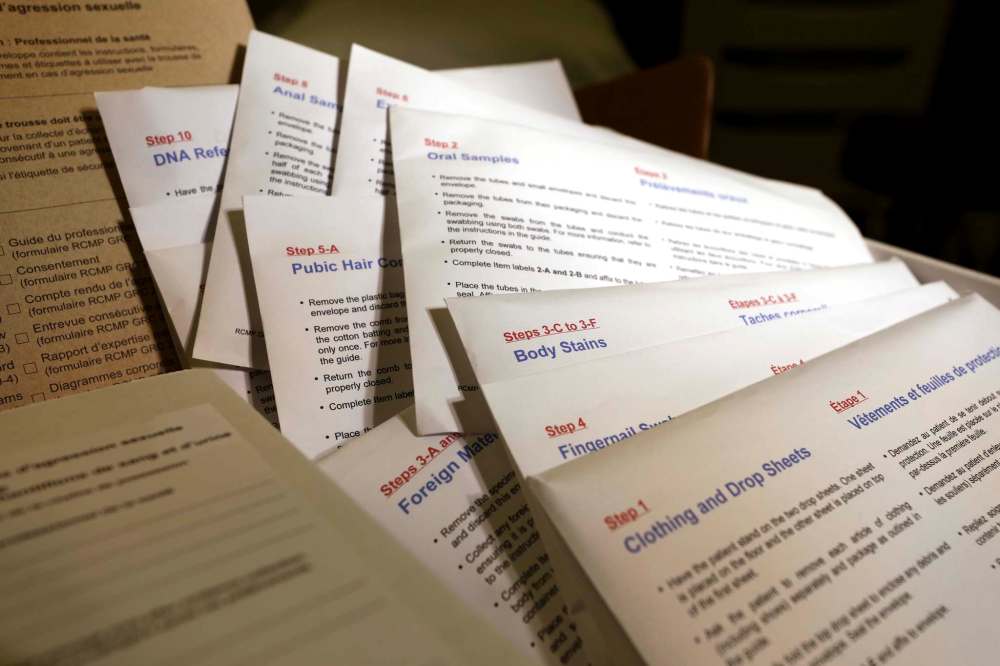

Smith is one of the go-to sources for staff education, often conversing with other regions about resources they should look at, how to navigate the RCMP sexual assault kit, and other notes on best practices.

While HSC’s SANE team is a leader, providing equitable care across the province is not as simple as replicating what the team does.

Once they’re trained, SANE nurses such as Smith maintain competency at HSC in part through patient volume. That’s not feasible in other regions, such as the Interlake-Eastern Regional Health Authority.

“If you had a certified SANE, their competence might become varied just because they’re not seeing very many presentations,” says Tracy Abraham, a nurse who works in administration at the Pinawa Hospital and was a member of the provincial sexual assault working group.

“In order to maintain your competency you have to be doing the work,” she says. You won’t have it if you’re only seeing a patient maybe once a year, nor will you have the comfort and confidence to help such a patient.

“It’s very difficult, actually, because you’re trying to make sure you’ve got all of your staff trained for the one-off situation,” Abraham says. “Do you train everyone or do you have champions at each site? But then what happens if the champion is on vacation?”

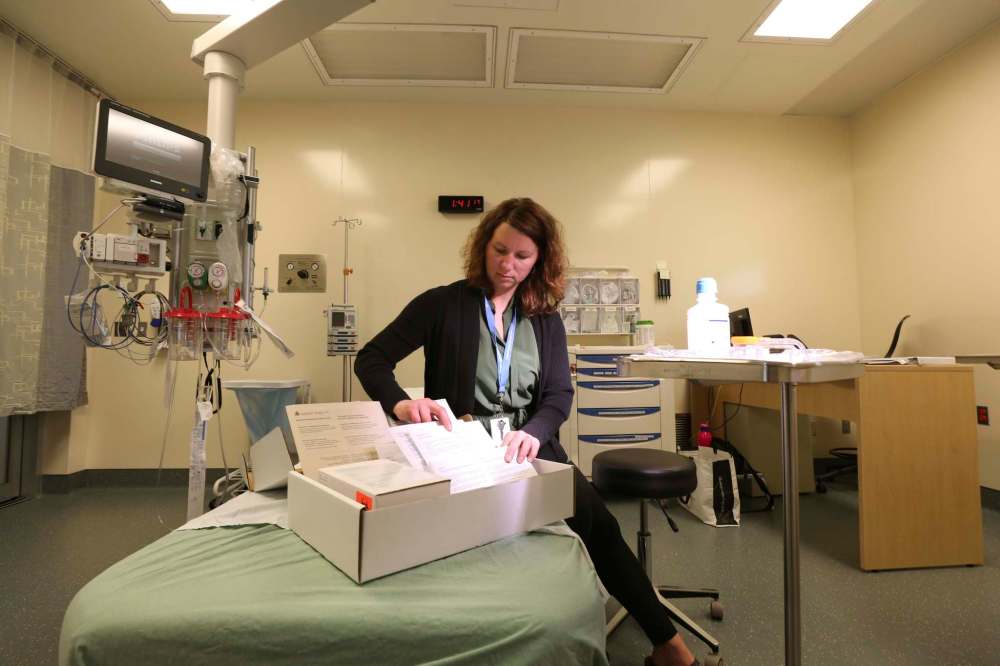

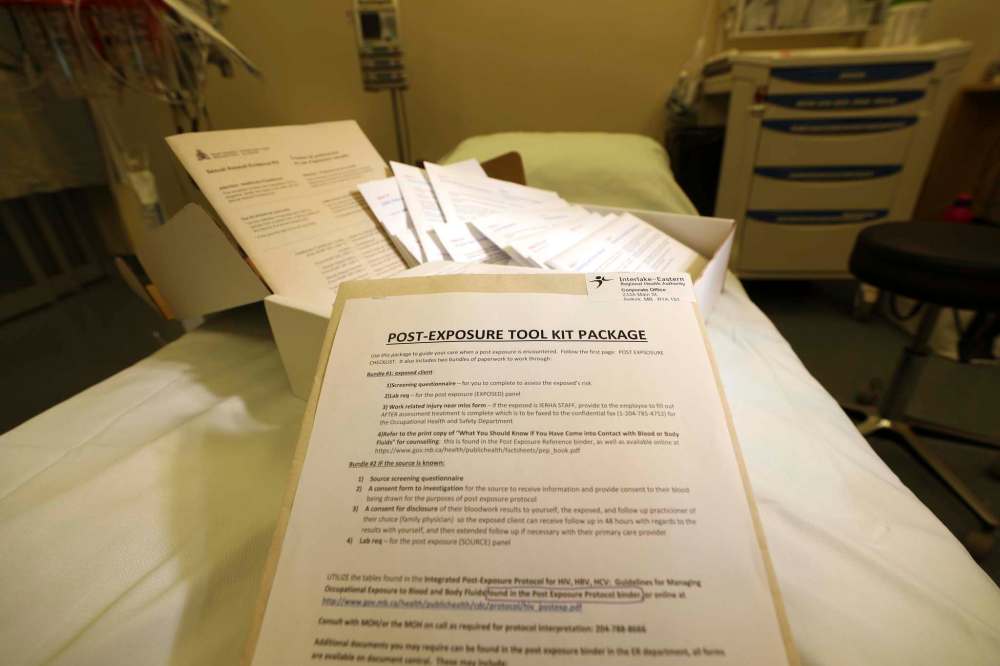

The Interlake-Eastern region just rolled out a new sexual assault policy that’s been in the works since it was formed out of the merger of the Interlake Regional Health Authority and the North Eastman Health Authority in 2012.

!function(e,t,n,s){var i=”InfogramEmbeds”,o=e.getElementsByTagName(t)[0],d=/^http:/.test(e.location)?”http:”:”https:”;if(/^/{2}/.test(s)&&(s=d+s),window[i]&&window[i].initialized)window[i].process&&window[i].process();else if(!e.getElementById(n)){var a=e.createElement(t);a.async=1,a.id=n,a.src=s,o.parentNode.insertBefore(a,o)}}(document,”script”,”infogram-async”,”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”);

So while it doesn’t make logistical sense right now to focus on SANE training, Abraham says they’ve made it so that there shouldn’t be the delay in service because of busy doctors that prompted Beth Ariss to look at creating a SANE program in the first place.

Now, anyone who presents at an ER in the Interlake-Eastern region will be cared for by a dedicated nurse, which will ensure not just continuity of care but also that the chain of custody — necessary should the case go to trial — is never broken. A physician will come in, Abraham says, for “some of the more sensitive areas of collection.”

And even though they may not see many cases in more rural ERs, Abraham says the “super user friendly” new RCMP sexual assault kits should help add to their comfort level on the rare occasions they do treat patients.

“It’s made it a lot easier for nurses and physicians to use,” she says.

Similar to HSC, where SANE nurses will call in Klinic to provide support, Interlake-Eastern also has access to the SARAH program from the Survivor’s Hope Crisis Centre. The volunteer-based community organization offers hospital accompaniment, follow-up support and referrals. They operate out of the Pinawa Hospital, Pine Falls Health Complex, the Beausejour District Hospital and, most recently, the Selkirk Regional Health Centre.

However, the region’s current policy doesn’t necessarily preclude the addition of SANE nurses in the future, according to Abraham. “It always has been” on the agenda, she says. Conversations around where they would be stationed, how they would be deployed, and how many the region would need are underway.

That’s true too in Southern Health and Prairie Mountain Health. All Female nurses in the Brandon Regional Health Centre’s emergency department are already SANE trained and have been for more than a decade. But, Scott Kirk, the hospital’s director of acute care, says the health authority is now looking at expanding that training to ER nurses in Swan River and Dauphin.

“The justification for it is it… to bring that service closer to home,” Kirk says. “We just want to be able to provide a more timely response.”

A spokesman for Northern Health says SANE training is already incorporated into broader training for ER nurses in the region. There are none currently in Southern Health, says the region’s chief medical officer Fortier, for the same reasons there aren’t any in the Interlake-Eastern region: not enough cases to maintain competency.

However, Fortier says, he doesn’t believe that’s a result of fewer sexual assaults in the area.

“I hope that’s a good news story but I’m not convinced,” he says. “I think there are people who are just not attending to the emergency rooms.”

At least one person has undergone SANE training in the region, according to information obtained through a freedom of information request, and the region is an active member in conversations around a provincial SANE rollout.

“It is absolutely on the radar,” Fortier says, SANE nurses are “an important resource that we need to address as a province.” To that end, he says, the sexual assault care recommendations before Shared Health “would probably see us trying to develop centres of excellence in certain parts of the province.”

● ● ●

Health Sciences Centre’s sexual assault program did not exist in 1975 when the Rape Crisis Information Centre opened. The independent support centre had five staff that manned two information lines and one crisis line. To ensure coverage, they partnered with Klinic a year later. Monday to Friday, 9-5, the rape crisis staff answered the phone lines while after hours the calls were forwarded to Klinic.

By 1978, the organization had been fully folded into Klinic. In the 1980s, there was joint training for volunteers who either answered phones on the original rape crisis line or on Klinic’s sexual assault line. The two eventually merged into Klinic’s sexual assault crisis program.

The women volunteers offer support in-person and over the phone. They provide follow-up counselling, advocacy work and other support. It has always been about survivors, says Gjerek, who has been at the helm of Klinic sexual assault program since the start of the 21st century.

So much has changed. There are crisis lines, support lines, the HSC sexual assault program, SANE nurses, the SARAH program, the Winnipeg Police Service sex crimes unit, numerous partnerships between organizations such as Klinic, the RCMP, and Ka Ni Kanichiihk.

Recently, Manitoba became Canada’s third province or territory to allow people who have been sexually assaulted to report their incidents to third parties, not the police.

Sage House at Mount Carmel Clinic, the Heart Medicine Lodge at Ka Ni Kanichihk and Klinic Community Health Centre on Portage Avenue will all accept reports of sexual assault, in person or over the phone from anyone across the province.

During the April announcement, Klinic’s executive director Nicole Chammartin said staff expect to see an increase in calls. Already, she noted, the #MeToo era has sparked increases beyond the annual 4,000 incoming calls about sexual assault.

But what hasn’t changed, Gjerek says, is the tenor of those calls.

“People are calling still with a lot of self-blame, still a lot of doubt or guilt, about what happened,” she says, “(they’re) really questioning their behaviour, their actions, how they contributed to this incident.”

She credits the #MeToo movement for helping give people whose assaults happened years, even decades, ago, the words necessary to reach out.

“It’s only now they’re feeling safe or comfortable enough to talk about it,” she says. “What the #MeToo campaign has helped to do is really create a broader understanding and awareness of what the scope of sexual violence is and that it really is a range of behaviours.”

That change is visible, Gjerek says, in the institutional support for sexual assault services. She points back to Beth Ariss and the original SANE nurses, working unpaid call to ensure HSC’s sexual assault program was always staffed. She calls Ariss a “powerhouse”; the SANE nurses have always been dedicated to the work, their employers just needed to catch up.

Now, there is a sexual assault response team in Winnipeg that includes Klinic, the HSC SANE program, the Winnipeg police sex crimes unit, and Ka Ni Kanichihk. There are regular meetings, frequent re-appraisals of how response protocols are functioning. The sexual assault working group has put forward recommendations to ensure equitable access to service even in the province’s more remote areas.

“Access is incredibly important, especially in our province where you have very far-flung communities,” Gjerek says — that the RHAs are looking at expanding the SANE program is “really critical.”

Change is slow but change is happening, she says, so now some of the focus needs to shift to teaching consent.

“The real gap is prevention education,” Gjerek says, “it’s looking at integrating this kind of training in our schools, teaching healthy relationships, healthy communication styles.”