The pervasiveness of sexual violence

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/08/2014 (3526 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Last September, two Canadian universities made national headlines, but it wasn’t because of a groundbreaking study or important research.

No, Saint Mary’s University in Halifax and the University of British Columbia came under fire for the same reason: leading hundreds of fresh-faced first-years in a frosh-week chant advocating rape. Both chants were variations on the following: “Y-O-U-N-G at UBC, we like ’em young, Y is for your sister, O is for oh so tight, U is for underage, N is for no consent, G is for go to jail.” At SMU, G was for “Grab that ass.”

The puerile but disturbing chants ignited a transnational debate about both the realities of campus safety and rape culture. Rape culture is a term coined by second-wave feminists in the 1970s to describe all the ways in which our culture tacitly accepts, condones and even encourages sexual violence through its attitudes about sex, sexuality and gender, which are shaped by everything from popular culture to religion.

Sides were quickly taken and battle lines drawn, fuelled by highly publicized rapes on U.S. campuses. Further international attention in the mainstream press came from the vicious gang rape and murder of a physiotherapy student on a moving bus in India after doing nothing more than having an evening out with her boyfriend at a movie theatre.

In 2014, no less weighty an institution than the Obama administration took the unprecedented step of setting up a task force on combating sexual violence on campus. As of August, 76 higher-learning institutions — ranging from public state universities to Ivy League members such as Harvard and Dartmouth — are under investigation for mishandling sexual-assault allegations.

But there was plenty of resistance.

Many pundits said the frosh chants at SMU and UBC were symptomatic of rape culture; many more outright denied its existence. “Don’t expect the notion of rape culture to die down any time soon,” wrote the Globe and Mail’s Margaret Wente. “Too many people have too much invested in it.” In March, CBC’s Q hosted a debate: Rape Culture: Accurate or Alarmist? That same month, Time ran a piece entitled It’s Time to End Rape Culture Hysteria.

But many leaders in the field would argue one need not look far to see examples of rape culture thriving on campuses — through reported high-profile cases, yes, but also the lack of such cases. Attaching big-picture statistics to the frequency and pervasiveness of sexual violence on campus is difficult, because 80 to 90 per cent of assaults go unreported. That, argues Ottawa-based social-justice activist Julie Lalonde, is rape culture at work.

“The power of rape culture is that we’re not allowed to talk about it. The silence is what perpetuates it. Cognitive dissonance also perpetuates rape culture,” she says.

Indeed, we live in a society that supposedly reviles rapists, yet is quick to blame the victim by focusing on what she wore, how many people she’s slept with, how much she drank that night, etc. Victims are often shamed and blamed; assailants are often sympathized with. “No one is going to stand up and say, ‘I support sexual violence,’ but that’s exactly what our actions and inactions say,” Lalonde says.

Mary-Anne Kandrack, a sociology professor at the University of Manitoba, is blunt about why people are so quick to reject the term ‘rape culture.’ “Well, then we’d have to admit that there’s an ongoing oppression of women. That term pulls into sharp relief that we remain less than, because it’s only someone who is less than that can be victimized in that way.”

Kandrack also believes the push-back against the term is rooted in a general discomfort with the idea we live in a culture in which sexual violence is condoned. “But the fact of the matter is, it is condoned. Only 10 per cent of assaults are reported, but many people would say it’s more in the neighbourhood of five to six per cent. It’s 2014, and we still haven’t made it safe for people to make those disclosures.” To that end, rape culture doesn’t just hurt girls and women. It hurts boys and men, too. “I tell my students, if society’s been this successful in silencing women, imagine what it’s like for boys and men?”

Rape culture wallows in misconceptions and distortion. Some believe it is a phrase trotted out to demonize men. Then there is the notion most rapes are of the “dark alley” variety, committed by an unknown perpetrator — as opposed to the far more common circumstance of the victim knowing the assailant beforehand.

It’s dangerous to ignore the fact that while not all men are rapists, an overwhelming number of rapists are men. “When and how and where did we socialize boys and men to think it’s OK to exploit, abuse and bring harm to someone else for their own pleasure? That’s what so angers me. We have communicated permission in some way, and that’s why I think people rebuke the concept (of rape culture),” Kandrack says. “We don’t want to own the permission we’ve given to young men.”

Sexual violence disproportionately targets women. Women account for nine out of 10 police-reported sexual assaults in Canada, and women aged 15 to 24 experience the highest rates of sexual violence. A 2013 fact sheet by the Canadian Federation of Students-Ontario quotes the most recent Statistics Canada General Social Survey, which says 70 per cent of self-reported sexual assaults were against women and almost half were against people aged 15 to 24. Young women also report the highest rates of being stalked, with stalkers known to victims in more than two-thirds of cases.

From the fact sheet: “Many on-campus sexual assaults occur during the first eight weeks of classes. More than 80 per cent of rapes that occur on college and university campuses are committed by someone known to the victim, with half of these incidences occurring on dates.”

In the United States, the oft-repeated statistic (by the White House included) is one in five female college students will be sexually assaulted during her time in school. It’s a hotly contested stat but, as Amanda Marcotte pointed out at Slate, that one in five women are assaulted does not mean one in five men are assailants. She references a 2002 study by David Lisak, a forensic expert on sexual assault and a retired professor of psychology from the University of Massachusetts Boston. Of the 1,882 men surveyed, six per cent had raped someone or attempted to do so. Most were repeat offenders. The 120 men in Lisak’s study committed 439 rapes. Zero were reported.

Alarmingly, many of the men in Lisak’s study didn’t see themselves as rapists. That speaks to how misinformed our young people are about what exactly rape is and what informed consent looks like. Lalonde would argue, for example, most people don’t know an intoxicated person is legally unable to give consent. In the high-profile 2012 case out of Steubenville, Ohio, where two football players raped a high school girl while party-goers looked on, one witness was asked why he didn’t intervene. “It wasn’t violent,” he responded. “I didn’t know exactly what rape was. I thought it was forcing yourself on someone.”

Rape — and rapists — don’t always look like the rape and rapists we see depicted on TV shows or the rapes that make the news — the stranger in the dark alley or the deranged madman. That feeds the myth of “real rape” — or “rape-rape,” as Whoopi Goldberg once called it, or “legitimate rape,” to quote former U.S. congressman Todd Akin — which is damaging for victims of acquaintance rape, often taken less seriously or met with skepticism despite the fact their experiences are more common.

“All rapes are brutal, but those during which a woman is murdered or beaten get a lot of media coverage,” says Jean Kilbourne, a media critic whose work focuses on the portrayal of women.

“When there’s a stranger serial rapist, the media will flock to it because it’s scary,” Lisak says. “Cable news will broadcast a local news conference all over the country. You don’t see that kind of attention paid to non-stranger cases. That’s still someone we’re dealing with. It’s very deep seated.”

That, argue feminist writers, fuels the idea “real” rape doesn’t happen on campus; that what happens on campus is so-called “grey rape.” Popularized by a 2007 Cosmopolitan piece written by Laura Sessions Stepp, the problematic term is often employed to describe acquaintance assaults, particularly those in which alcohol is involved. The article defined grey rape as “sex that falls somewhere between consent and denial and is even more confusing than date rape because often both parties are unsure of who wanted what.”

And when survivors are told their rape doesn’t match a pop-culture depiction of the crime, they often assume the blame and the silence continues.

Kilbourne relates a story from a professor who was raped and almost murdered, who said it was almost easier for her to deal with the trauma. “Because she was so clearly left for dead, no one accused her of ‘asking for it.’ ”

Binge-drinking and hookup culture figure prominently in university life. If we’re to believe popular culture, getting wasted and hooking up at a college house party is not only a rite of passage, it’s a pastime as American as baseball, as Canadian as hockey. Young people — with varying degrees of sexual experience and education — are living on their own for the first time unsupervised and are looking to blow off steam. A party-hearty mentality, combined with little to no discussion about safe sex, informed consent and safe partying — as well as a college administration sometimes turning the other cheek — can have disastrous consequences.

The subject of alcohol and campus sexual assault is a thorny one. Slate’s Emily Yoffe cautioned college women last fall they may “end up getting raped” as the result of their drinking. Many columnists — myself included — took issue with her position, which puts the responsibility for an attack on women. Yoffe’s column speaks to both the pervasiveness of victim-blaming and the fact our society has accepted rape as an inevitability.

Still, there’s room for a discussion about alcohol. “Alcohol is not the cause of sexual assault — sexism is the cause,” Kilbourne says. “But it is a contributing factor that needs to be addressed. Alcohol is the primary date-rape drug. People talk about roofies and slipping drugs into drinks — and that certainly happens — but perpetrators hell-bent on assaulting women are most likely to get them drunk. They are using alcohol deliberately.”

The focus, then, should be on the assailants.

Kandrack, like Kilbourne, argues we need to re-examine the starring role of alcohol in our culture, in general. She says we need to stop romanticizing it and start problematizing it — for both genders.

And yet, the pearl-clutching is often reserved for young women. “We are failing to let women know that when they render themselves defenceless, terrible things can be done to them,” Yoffe wrote. Except women are told they are targets for violence all the time.

“Our culture is swimming with examples of women — in movies, television and real life — who are ‘punished’ for their ‘bad choices’ with sexual violence,” wrote Salon’s Katie McDonough. “‘Bad choices’ include wearing a short skirt, staying out too late, getting too drunk, trusting too much. The list of reasons Americans believe women deserve rape is long.”

Kilbourne says: “Rape is not the penalty for being drunk.”

IN JUNE, students in Kandrack’s Women, Crime and Social Justice class held a presentation at the U of M called Challenging Rape Culture: Myths and Misconceptions about Sexual Assault. Students showcased public-service announcements they had created around a myth or misconception — women ask for it; women are not to be trusted; stranger danger, etc. “In my mind, one of the most disturbing implications or misconceptions is that people equate sexual violence with sex,” she says. “Somehow, it occurs in the context of a sexual encounter that goes wrong. The two have absolutely nothing to do with each other.”

The campaigns the students came up with were inspiring. “Gum is something you ask for, sexual assault is not” is emblazoned on packages of gum that have been produced and will be passed out during orientation week. (The package also bears the hashtag #nomoreblurredlines).

Another campaign saw students flip the script on a ‘No Means No’ PSA that features a man being sexually harassed by a woman. Kandrack says that PSA was initially met with laughter — until, of course, the tag line appeared on the screen. “Why are you laughing? No matter what the circumstance, no means no.”

Dismantling myths and misconceptions about sexual assault is an important part of dismantling rape culture. The Washington Post’s George F. Will drew ire with a June column criticizing the Obama administration’s crackdown. “(Colleges and universities) are learning that when they say campus victimizations are ubiquitous (‘micro-aggressions,’ often not discernible to the untutored eye, are everywhere), and that when they make victimhood a coveted status that confers privileges, victims proliferate,” he wrote. (I’m not sure many survivors would call victimhood a “coveted status.”)

Will is worried about all those men who are going to be falsely accused, which plays into the idea most women who accuse men of sexual assault are liars who regret an “encounter gone wrong” and are intent on destroying the lives of innocent men. “If you were falsely accused of something, it would be a damaging experience, no question,” Lisak says. “There have been good studies going back more than a decade that suggest while false reports happen, the number is between two per cent and eight per cent — and eight per cent is generous. It’s five per cent at most. It’s not a significant problem.”

We aren’t used to hearing women say no and being respected for that decision, says Fiona Green, associate dean of arts at the University of Winnipeg. “Women have to learn to say no and mean it” is a popular refrain from everyone from anonymous keyboard crusaders in comment sections to Dr. Phil. But many would argue our culture does not support women who say no.

We still live in a culture in which an assertive woman is labelled a bitch, Green says. Many young women and men are seeking community at university; they want to fit in. Pop culture has long fetishized the Cool Girl — “a chick who can hang,” to quote comedian Amy Schumer. “There are not many pop cultural role models of women who know their own minds and don’t conform to what’s expected of them and be rewarded for it,” she says. “It’s about how we all internalize the expectations of our gender. Boys are expected to sleep with lots of girls because that’s how their masculinity is evaluated. For girls, it’s OK to be sexually involved with a long-term, monogamous partner — but it’s not OK to be ‘too’ sexual, a number that changes relating to class, age and historical times.”

Women and girls are socialized to appease and acquiesce. “We’re still teaching girls, ‘Don’t hurt people’s feelings.’ God forbid you should assert yourself,” Kandrack says. “When it comes time to say no and mean it, have we given them licence to? If we’re going to keep on insisting girls care more about other people’s feelings than their own, we ought not to be surprised that we’re not teaching them how to say no.”

We also do too little to teach girls or boys about sexuality and sex.

Green says traditional sex education in public schools seems to focus on procreation and not getting diseases and not about development as sexual beings. “We learn about sexuality from porn,” she says “We learn about it from our friends, who are often misinformed. We internalize our parents’ hang-ups and the hang-ups of their parents.”

Most sex-education messages remove pleasure from the conversation, presumably to discourage kids from having sex. “When we don’t expect sex to be a mutually satisfying experience shared by two people, it leaves us vulnerable to some truly poisonous alternative ideas, including the stubborn myth that sex is a precious commodity that men acquire from women,” writes Jaclyn Friedman in a Time op-ed. “Under this paradigm, women’s bodies are a means to an end for men, whether that end is physical gratification, validation of their masculinity, or both.”

Friedman was writing after May’s Isla Vista massacre, in which Elliot Roger, 22, murdered six people before committing suicide. He was a college student, a virgin who felt it was a “crime” and an “injustice” that women were not attracted to him. He was a “nice guy;” he felt women owed him love and sex. He felt entitled to their bodies. And when he couldn’t “get some,” he opened fire.

And it was, once again, called an “isolated incident” by a “deranged madman” by people who fail to realize the Elliot Rogers of the world are shaped by the culture they live in. Rape culture hurts everyone.

In July, Dartmouth hosted a summit on sexual assault on campuses organized by Lisak and Claudia Bayliff, an attorney with almost three decades’ experience in the field. The goal: to educate campus and community stakeholders on sexual-assault prevention, education and response as well as provide the chance for institutions to develop policies for their own campuses. “For me, personally, it was a highlight,” Lisak says. “I do all kinds of grim work, and I’m hard-pressed to find things that are uplifting. But this was genuinely uplifting.”

Kilbourne agrees it was a watershed, reflective of a shifting climate. “(U.S. President Barack) Obama is the first president, as far as I know, to talk about sexual violence. It’s quite something to have the government look into it,” she says. Survivors, she says, were now coming forward. “They mostly didn’t because they were blamed and shamed and nothing happened to their assaulters — maybe their rapist would have to write a paper or something stupid like that. That didn’t inspire young women to come forward.”

As with any problem, the first step is admitting there is one. In Canada, some schools are also cracking down; the University of Ottawa suspended its hockey program for the 2014-15 season and fired the head coach after a February incident in Thunder Bay. Two former players, Guillaume Donovan and David Foucher, have been charged with sexual assault.

Experts say bystander intervention can be effective in preventing sexual assault. “Women, but especially men, are being encouraged to step up and intervene,” Kilbourne says. And not just when they witness an assault. “Intervene when sexist jokes are told. Intervene when you know that there’s a guy in your fraternity who likes to get women drunk and isolate them. There’s been some evidence that it makes a big difference. And we’re talking about intervening on an elementary level. Like saying ‘that’s not funny,’ when you hear a rape joke. It takes courage to do that.” Lalonde developed and manages draw-the-line.ca, a bystander-intervention campaign created by the Ontario Coalition of Rape Crisis Centres. The campaign challenges myths about sexual violence and gives bystanders the tools to intervene safely and effectively. Lalonde wants to see more campuses “be brave enough to flip the script and say it’s a conversation about consent and respectful relationships and not stranger danger.”

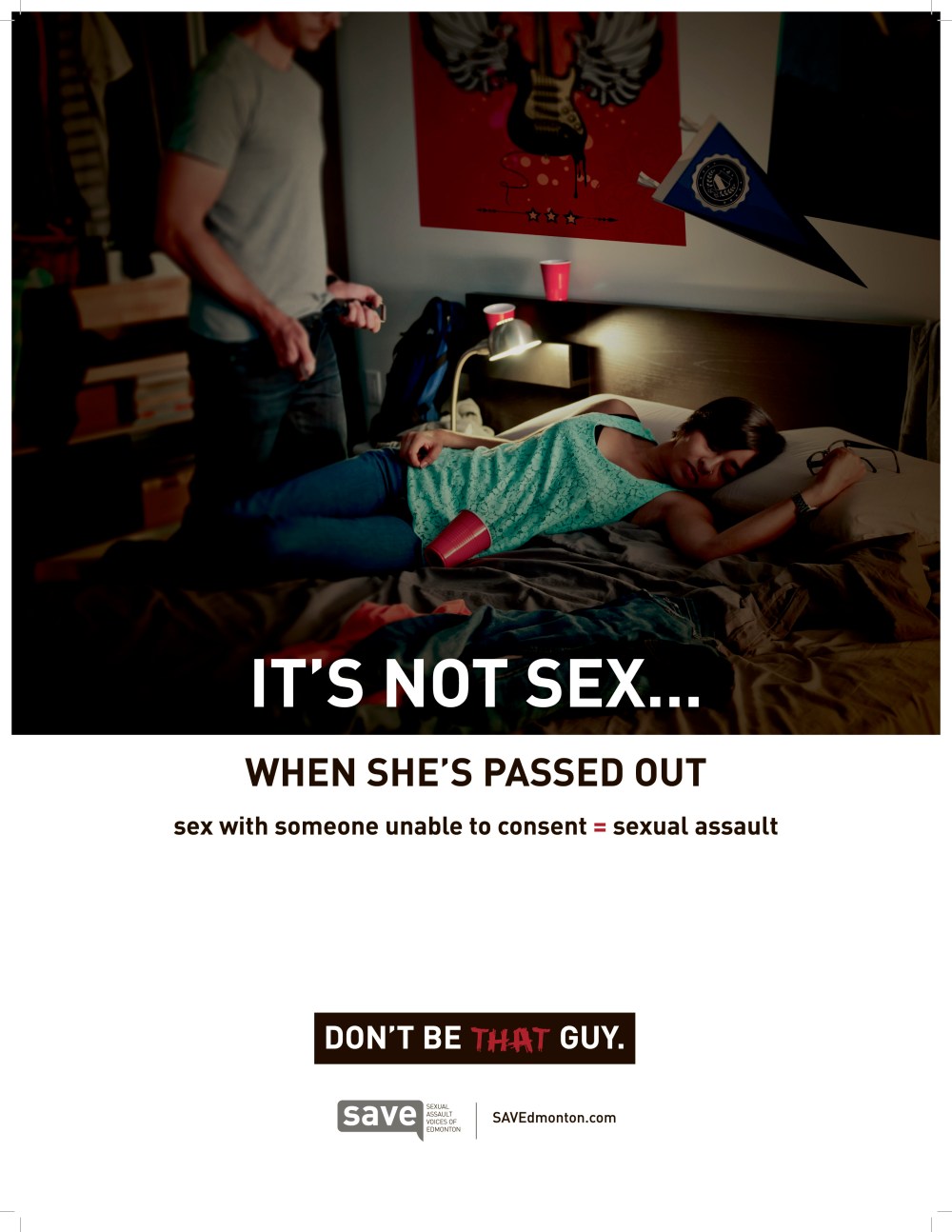

Sexual-assault prevention has historically been targeted at women via well-worn ‘ladies’ safety tips’. Several viral posts, such as Leigh Hofheimer’s rape-prevention tips — “Carry a rape whistle. If you find that you are about to rape someone, blow the whistle until someone comes to stop you” — have put the focus on the perpetrator. Offline campaigns — such as the Don’t Be That Guy drive launched in Edmonton — are doing the same. Changing attitudes about sexual violence will take time. “It’s a long, long process of erosion,” Lisak says. But the conversation is happening. In 2007, when Lalonde and fellow graduate student Lesley Claire created the Coalition for a Carleton Sexual Assault Centre in response to a high-profile sexual assault, “no one was talking about sexual assault on campus. We were ripping off Band-Aids all over the place. Now, there’s a conversation happening. Media is still covering the story.”

Sexual violence is a problem that belongs to all of us. The sooner we own it, the sooner we can all work together to stamp it out. As Kilbourne says, “This isn’t just a women’s issue. We all need to look out for each other.”

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Jen Zoratti

Columnist

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.