Obstacles to oversight: IIU has been thwarted by members of WPS The police watchdog's civilian director has repeatedly raised concerns about a lack of co-operation from city police that appear to have been ignored by Chief Danny Smyth, the Free Press reveals

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/11/2018 (1978 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The young man steps onto the road, his stride quick as he cuts across the street. He has no idea what’s about to happen; he has no idea he’ll never see his family again.

A loud thud echoes into the night. The young man’s body soars, twisting and turning through the air. The sound of his head cracking against the pavement fills the eardrums of a witness as the vehicle drives away.

Outside the Sutherland Hotel on Main Street, the young man lies dying next to the curb near a garbage can. His name is Cody Severight and he’s 23 years old. His runners, a pair of grey-coloured Nikes, are photographed several feet apart alongside the evidence tags that come to litter the road.

It is the night of Oct. 10, 2017.

Thirty minutes later, the alleged driver, 34-year-old Justin Holz, a constable with the Winnipeg Police Service, places a phone call. He wants to turn himself in. He’s taken into custody seven kilometres north of the crash scene.

The Independent Investigation Unit of Manitoba — the province’s civilian-led police oversight agency — quickly takes control of the case. Charges are laid, including one of impaired driving causing death.

As details begin trickling out through the press, it’s alleged Holz had been out drinking with other officers at a bar located just around the corner from the downtown police headquarters in the hours leading up to the fatal hit-and-run.

What begins as a whisper is later confirmed by the chief of police at a hastily called press conference: it took up to four hours before Holz was given a breathalyzer. Nevertheless, the chief promises justice will be done.

Ten days after the crash, the scope of the IIU probe widens. A secondary investigation is opened into the “irregular and improper” conduct of two additional WPS officers in the aftermath of Holz’s arrest.

Rumours are swirling; the investigators are looking into why it took so long for a breathalyzer to be administered. The WPS and IIU both remain tight-lipped.

The incident resurfaces dark memories for Manitobans. Another fatal crash. An officer drunk behind the wheel. A dead wife and mother. A botched police investigation. Lives forever changed. Accusations of a coverup.

But when that tragedy unfolded in February 2005, the IIU didn’t exist. Police no longer investigate police. The two WPS officers are suspended, pending the outcome of the investigation.

Two months later, the officers are cleared of wrongdoing, sparking outrage from the victim’s family. In a press release, the IIU civilian director says he’s not convinced the officers acted to “intentionally” obstruct justice or impede investigators.

For those intimately connected to both cases, it’s déjà-vu. Can this really happen again?

Like clockwork, each time the IIU opens an investigation, it issues a news release. Another will come when the probe is complete, briefly outlining the findings.

A final report is also filed, but sometimes not until weeks, if not months, later. Since the IIU began operations June 19, 2015, 56 reports have been finalized.

In some cases, no report has been issued and no timeline exists for when one must be released.

Those releases and reports, however, paint only a partial picture of the police watchdog and its work. The agency’s full story is found in private letters and emails, internal documents and reports and investigators’ notebooks.

And that story involves disappearing complaints, skirted investigations, institutional pushback, disputes over jurisdiction and interference among officers identified in criminal probes.

That’s the hidden record of the IIU that’s come to light during an eight-month Free Press investigation.

During that time, the Free Press filed eight freedom of information requests, reviewed hundreds of pages of internal documents and correspondence, compiled clearance-rate statistics never before tracked and conducted more than 20 interviews.

Two questions, in particular, led to those efforts:

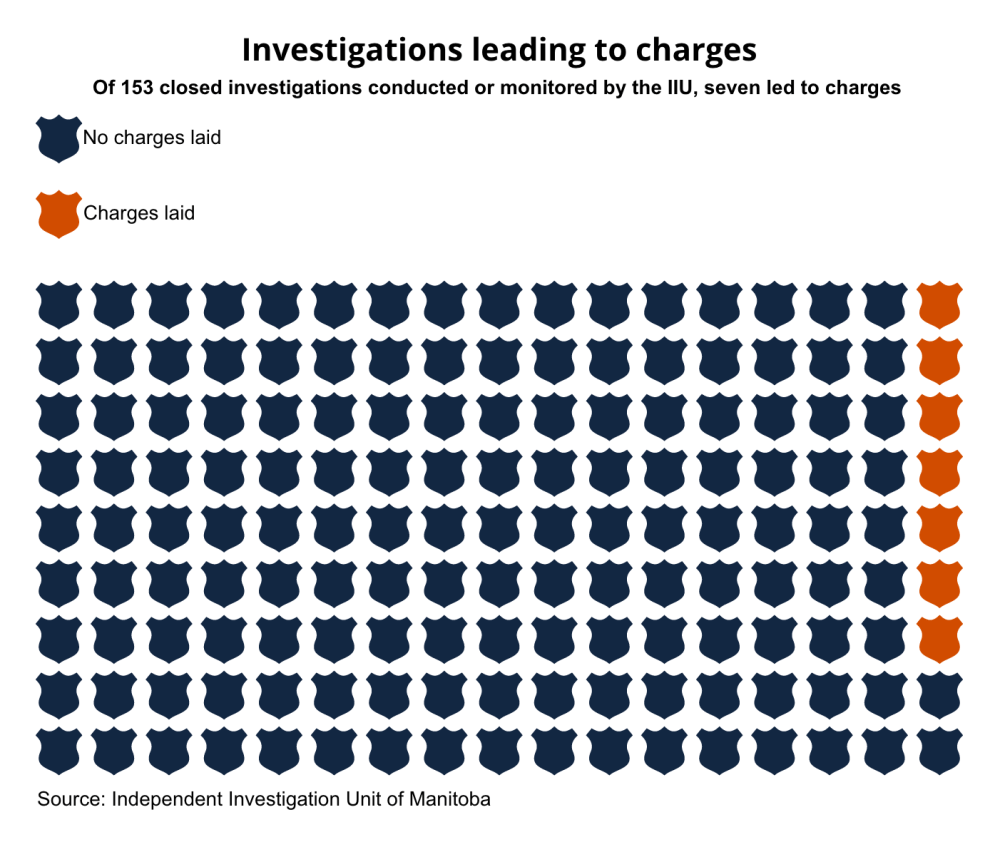

In nearly 3 1/2 years, why have only seven — or 4.5 per cent — of 153 investigations conducted or monitored by the IIU led to criminal charges?

(The IIU later clarified it does not track statistics for charges laid in cases it monitors; it’s possible charges were laid that are not reflected in the data provided by the agency).

What is the relationship between the IIU and the WPS?

This is the first story in a four-part series outlining what the Free Press has learned. In particular, this series will focus on patterns of disappeared criminal complaints, interference and a lack of co-operation among officers and repeated disputes over jurisdiction between the IIU and the WPS.

Only two WPS officers have faced charges stemming from IIU investigations and — thus far — there have been no convictions. One of them is Holz, now 35, whose case is still before the court. He is no longer a member of the WPS, although the department will not say if he was fired or if he resigned.

The other is 44-year-old Christian Paul Guyot, who was charged with assault after video footage surfaced that appeared to show him striking a 12-year-old boy while responding to a disturbance call at an Inkster Boulevard home in August 2017.

He was found not guilty on Sept. 26, 2018 in a controversial case in which the prosecutor introduced no evidence to prove that Guyot was even a member of the WPS, let alone the officer depicted in the video.

In total, eight Manitoba police officers have been charged in seven IIU investigations. The small number of charges needs to be contextualized within the level of co-operation the IIU has received.

Internal documents reveal Manitoba law enforcement agencies, particularly the WPS, have long resisted the IIU’s mandate, either by refusing to co-operate with investigators or stifling civilian complaints entirely.

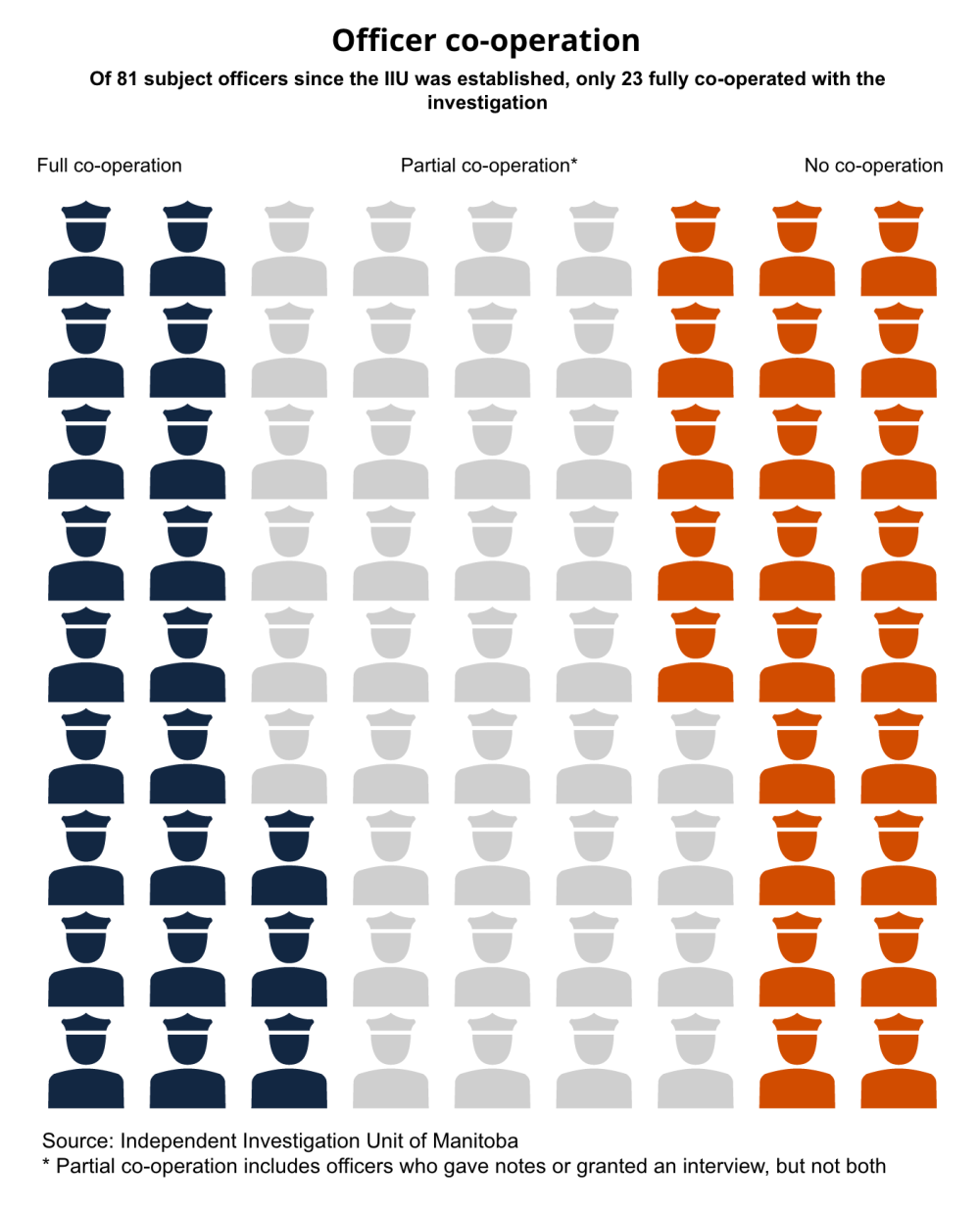

The Free Press analyzed all 56 final reports written by IIU civilian director Zane Tessler that have been released to the public. In those cases, 81 police officers were identified as “subject officers,” meaning criminal charges could be laid against them.

Of those 81 officers, 60 refused to hand over their written notes or sit down for an interview, sometimes both. In other words, 74 per cent refused full co-operation with investigators.

Some officers ignored the IIU entirely and refused to respond to any formal requests. Others showed up only to read prepared statements, with legal counsel in tow.

Under the Police Services Act — which is the legislation governing Manitoba law enforcement — officers cannot be compelled to co-operate during these investigations.

However, resistance among officers has not been limited to behaviour protected by legislation; at times, the line has been crossed into activity that undermines — not just resists — IIU probes.

That includes officers discussing events being investigated among themselves prior to meeting with the IIU and, on at least one occasion, the circulation of a subject officer’s written report among colleagues.

When caught contravening clearly defined rules governing police conduct during IIU probes, officers faced no apparent repercussions.

Resistance to the IIU has not been limited to police rank and file. Top WPS brass, including Chief Danny Smyth, has also pushed back, refusing to hand over requested materials and disputing the watchdog’s right to investigate certain cases.

While the IIU is expected to file annual reports to Manitoba Justice, only one report has been publicly released so far.

An IIU spokeswoman said the agency filed annual reports for the 2016-17 and 2017-18 fiscal years, but — for an unknown reason — the department failed to properly pass them along to the minister’s office.

As such, the reports have yet to even be tabled at the provincial level. In addition, Manitoba Justice has not conducted any internal reviews of the watchdog, further suggesting a lack of oversight.

When the documents obtained by the Free Press were shown to academics, police oversight experts, retired law enforcement and former members of the Manitoba Police Commission, multiple interviewees questioned whether the IIU is a paper tiger.

Sheila Bedi, clinical associate professor of law at Northwestern University near Chicago, whose academic work focuses on police misconduct and accountability, said she questions the ability of any oversight agency to fulfil its mandate with the level of co-operation the IIU has received.

“If officers are not required to participate in the investigation, it’s very difficult to imagine how oversight could be effective. Of course, they should have the right against self-incrimination, but they should participate in the interview process,” Bedi said.

She mentioned several red flags that can help investigators identify coverups of police misconduct, including efforts by officers to get on the same page prior to filling reports or sitting down for interviews.

“There are certain hallmarks of coverups. Things like boilerplate language in police reports, the same language in multiple reports, general language,” she said.

“Cut-and-paste jobs where officers are essentially copying off each other, reports that really do not go into the specific actions that an officer took. These are all things that should raise questions.”

After years of effort and a significant investment of taxpayer dollars, the IIU was launched amid much fanfare in June 2015.

The day the unit went operational was a day of hope for many people who had long raised concerns about a system that allowed police to investigate accusations levied against their colleagues.

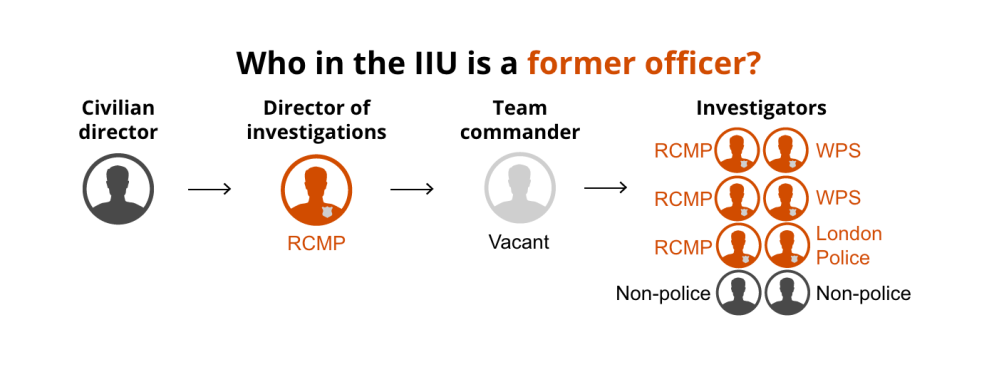

The IIU, which operates on an annual budget of $2.3 million, is composed of a 10-person investigative wing staffed, primarily, with former police officers. It is led by civilian director Zane Tessler, a former Crown prosecutor.

The newly formed unit was faced with a tall order: when police are accused of criminal behaviour, restore public faith that they’ll be held to the same standards as anyone else.

After years of scandals, accusations of preferential treatment, expensive inquests, alleged coverups and tensions with Indigenous peoples, the birth of the IIU was sold as a new, unprecedented chapter for law enforcement accountability in Manitoba.

But for most of its first year, the agency was unable to fulfil that mandate because of the behaviour of the WPS professional standards unit, which went about its business as though nothing had changed.

Historically, the PSU was responsible for handling accusations against WPS members in-house. The IIU was created, in part, to put an end to that practice.

Instead, month after month, the PSU operated as if the IIU didn’t exist.

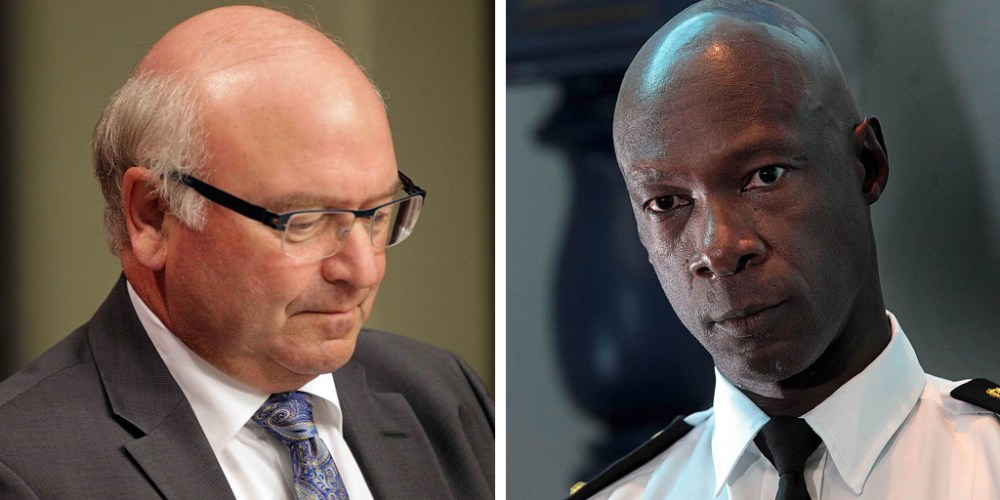

PHIL HOSSACK / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS FILES Left: IIU civilian director Zane Tessler. Right: Former police chief Devon Clunis.

The PSU, which reports directly to the chief of police, kept criminal accusations against officers from the agency responsible for investigating them. It’s not clear how many officers were shielded from IIU investigations during that period.

On March 2, 2016, Tessler informed then-WPS Chief Devon Clunis that he’d learned of the practice. In an email, he outlined how — eight months and 12 days after the IIU began operations — it had become clear the PSU was breaching the Police Services Act.

Zane Tessler: To: Police Chief Devon Clunis

Re: Notifications to the IIU

Date: March 2, 2016

…I am concerned that there may be internal criminal investigations of WPS members that are not brought to the attention of the IIU, as required by law. In that regard, the IIU is forestalled from discharging its legislative mandate of providing oversight and, when appropriate, undertaking independent investigations into such matters.

He went on to explain how he’d become aware of the situation. The following section of the email — which discussed a specific investigation into a named officer — is redacted. (This is often the case with documents obtained through freedom of information requests).

Nonetheless, it’s clear Tessler was “very concerned” by what he’d discovered. He said the PSU was breaking the law by delaying — if not discarding — notifications of criminal complaints.

Between June 19, 2015 and March 2, 2016, the IIU opened five investigations into WPS officers. Four of them involved suspects dying or being killed during altercations with police; the last left a suspect in hospital with “serious injuries.”

Incidents where the action, or inaction, of a police officer results in serious injury or death trigger automatic IIU investigations. These cases are often so high-profile that keeping the IIU in the dark would be impossible.

But when an officer is accused of misconduct that doesn’t result in serious injury or death — for example, excessive force or improper storage of a firearm — it is up to the IIU civilian director whether to open an investigation.

For that process to work, however, the WPS has to operate on the honour system. The police have to inform the IIU whenever a criminal accusation is lodged against one of their own.

Instead, the PSU appears to have notified the IIU only of incidents that triggered automatic investigations. Cases that didn’t trigger automatic probes were handled internally.

The IIU was notified only if the PSU found sufficient evidence to lay a charge following its own investigation. That happened just one time, and is what led to Tessler becoming aware of the behaviour.

If the PSU decided there was insufficient evidence, the file was closed. This gave the PSU the ability to make criminal complaints against fellow officers disappear. In the email, Tessler said this rendered IIU oversight in these cases a “nullity.”

Zane Tessler: To: Police Chief Devon Clunis

Re: Notifications to the IIU

Date: March 2, 2016

…The investigation has been substantially completed and a formal charge laid before the civilian director has considered whether the public interest requires independent investigation. It would appear that the decision to notify the IIU is directly connected to the decision to arrest and charge the officer after a substantial portion of the investigation was undertaken.

What this practice ensured, Tessler wrote, was that in cases where the PSU decided no charges should be laid, “the IIU will never know of the existence of the complaint or investigation.”

Put simply, it wasn’t the PSU’s call to make. Tessler called the practice “troubling” and asked for a full list of all internal investigations conducted since the IIU began operations. He signed off by saying the matter called for an “immediate and clear resolution.”

There’s no evidence Clunis — who was one week away from announcing his retirement — responded. A handwritten note suggests then-deputy chief Danny Smyth followed up on his behalf.

The note mentions that plans were made to respond in full at a later date. That response did not turn up in the freedom of information requests filed by the Free Press.

Smyth declined an interview request for this project. In a short written statement, he admitted there were “growing pains” during the first months after the IIU went operational, but said the two agencies have a positive professional relationship.

FULL WRITTEN STATEMENT FROM WPS CHIEF DANNY SMYTH

“I will not be commenting on specific cases. As for the relationship with the IIU, I can say that we have a positive professional relationship with that agency. Civilian Director Zane Tessler and I communicate and meet with one another routinely.

“I will not be commenting on specific cases. As for the relationship with the IIU, I can say that we have a positive professional relationship with that agency. Civilian Director Zane Tessler and I communicate and meet with one another routinely.

“As with any new protocol, there were what I would characterize as “growing pains” at the beginning of its mandate. At times, we have disagreed on the interpretation of regulations as they pertain to officer involved conduct. We have worked through those matters when they arose.

“The Winnipeg Police Service is committed to ensuring the success of civilian oversight as it pertains to police governance, and more specifically independent investigation of officer involved incidents that fall within the jurisdiction of the IIU as prescribed under the Police Services Act.”

Tessler also declined an interview request; instead, the IIU agreed to provide written responses to written questions.

Despite Tessler’s request for a full list of internal investigations withheld by the PSU, an IIU spokeswoman confirmed the WPS did not turn one over. No further action was pursued by the IIU and it appears no meeting was held for Tessler and Clunis to discuss this issue.

When asked what — if any — disciplinary or corrective measures were taken against the PSU, she directed the Free Press to the WPS.

“There was no suggestion of any intentional effort on the part of the professional standards unit to be obstructionist,” the spokeswoman wrote.

“(The) IIU does recognize there was a learning curve for police agencies when the office first became operational in 2015. The number of notifications from the WPS to the IIU has continued to grow, indicating the service is becoming more aware of its obligations.”

In the only annual report the IIU has published on its website, which documents its record from June 19, 2015 to March 31, 2016, there is no mention of the withheld accusations.

The patterns of behaviour exhibited by the PSU continued long after Clunis retired in March 2016. On Nov. 4 that year, Smyth — the son of a former WPS officer — was named the new chief of police.

Three weeks later, Tessler sent him an email saying the IIU was still not being notified of all criminal accusations made against WPS officers. He would make similar complaints in subsequent emails to Smyth in March and August 2017.

The first incident concerned an accusation of excessive force during an arrest in the North End. The allegation was kept from the IIU; Tessler became aware of it only after it was reported by two local news outlets.

Cellphone footage taken by a concerned citizen shows an officer twice strike a man lying on his stomach with his hands cuffed behind his back. The man was taken to hospital and treated for injuries.

That footage was obtained by the CBC, which showed it to police spokesman Const. Rob Carver. He said the officer had been cleared of wrongdoing by a use-of-force expert, claiming it wasn’t unusual for police to resort to force even if a suspect is handcuffed on the ground.

The arrest in question occurred on Nov. 22, 2016 and Carver appears to have been asked about it three days later, on Nov. 25.

Zane Tessler: To: Danny Smyth

Re: Violent arrest violation

Date: Nov. 28, 2016

The most disconcerting comment attributed to Const. Carver was that he confirmed that (the) WPS has reported this incident to the IIU but was unclear if an investigation will follow at this point. I can tell you with certainty that this office has not received a (notification), formally or otherwise, or in fact any notice of this incident other than my reading about it on two online services, days after the fact.

Tessler asked why the WPS would not notify the IIU given that an accusation of excessive force would “invariably involve an investigation into whether the conduct constitutes a contravention of the Criminal Code.” He also pressed Smyth to explain why Carver would misinform the media.

“It is imperative we discuss this matter immediately,” he wrote.

The Free Press did not find any response from Smyth as a result of its freedom of information requests. However, that does not mean the chief didn’t follow up through other means, or have someone respond on his behalf.

In the IIU’s written statement, the spokeswoman declined to comment on what may have motivated this conduct and again directed the reporter to the WPS. A request to interview Carver was not granted prior to publication.

The IIU spokeswoman did say that after Tessler sent this email, the IIU was given a formal notification of the complaint and the matter was subsequently investigated.

“There is no way for the IIU to know (how often the WPS fails to notify it of an accusation) and the agency won’t speculate as to how frequently this may occur,” the spokeswoman wrote.

“Ultimately, it relies on the integrity of the police service and chief to notify the IIU as required.”

In a written statement, Tessler said that despite these incidents, Manitobans can rest assured that the IIU has gotten good co-operation from all police departments in the province.

When disputes happen, they’re usually over differing interpretations of the Police Services Act, Tessler said, adding they are handled on a case-by-case basis.

“Co-operation from all Manitoba police agencies has generally been good…. There was a learning curve in the first couple years of operation, and the IIU has provided — and continues to provide — continuing education for all front-line officers and management,” Tessler wrote.

“But that it not to say there (have) not been occasional disputes or pushback.”

On May 26, 2017, more than 23 months after the IIU became operational, Tessler again reached out to Smyth to complain that the PSU was withholding accusations.

WRITTEN STATEMENT FROM IIU CIVILIAN DIRECTOR ZANE TESSLER

On the high percentage of subject officers who refuse to turn over notes or sit down for an interview, if not both:

“A statutory privilege to remain silent and not be compelled as a witness against him or herself exists for the benefit of subject officers. This privilege is the same as is provided under constitution rights to all persons. While this can make an investigator’s job more challenging, the IIU absolutely respects the subject officer’s right to remain silent. On the other hand, designated witness officers are required to co-operate fully with IIU investigations.

On the high percentage of subject officers who refuse to turn over notes or sit down for an interview, if not both:

“A statutory privilege to remain silent and not be compelled as a witness against him or herself exists for the benefit of subject officers. This privilege is the same as is provided under constitution rights to all persons. While this can make an investigator’s job more challenging, the IIU absolutely respects the subject officer’s right to remain silent. On the other hand, designated witness officers are required to co-operate fully with IIU investigations.

“You should not confuse a subject officer’s statutory right not to be compelled to co-operate with the suggestion that co-operation is lagging. Many subject officers have co-operated in IIU investigations by providing notes, statements and participating in interviews.”

On whether the small number of charges laid by the IIU constitutes a success:

“The IIU’s measure of success is not whether or not charges are laid, or what number of charges are laid. The IIU’s mandate is to investigate a matter thoroughly and impartially to determine the facts surrounding an incident. It is important to understand that the IIU never pre-supposes whether an investigation should lead to charges against an officer. We consider a thorough, complete, impartial investigation a success.

“In turn, the public having confidence that a full and fair investigation was done should also be considered a success. If a subject officer is cleared following an investigation, that should be considered a success. If charges result or are authorized following a full and impartial IIU investigation, that will also be considered a success. In isolation, the number of charges laid is not an indicator of success or lack thereof.”

On whether it’s problematic that the majority of IIU investigators are former police officers:

“Investigators are under my sole command and direction as civilian director, and I myself am prohibited by legislation from having ever worked for a police force. The most important and primary factor is for the IIU to hire as investigators the most qualified and experienced individuals and who have demonstrated the highest level of integrity in their work.

“We have engaged investigators with non-police backgrounds in our investigative teams. In addition, our case management processes and internal fail-safe reviews provide multiple layers of oversight to further guarantee impartiality. In the end, the civilian director is solely responsible for the decisions out of the investigations and publicly reports all findings.”

The incident involved another allegation of assault lodged against a WPS officer. In the email, Tessler said that someone had approached the IIU with the accusation.

Since the IIU does not directly handle civilian complaints, Tessler informed this individual that a formal report would need to be filed with the WPS.

“I advised that the appropriate course would be to contact (the) WPS and file a formal complaint of the assault allegation. The IIU would then be notified by the police service,” Tessler wrote.

Sometime later, the IIU was again approached by this individual. The person said they had contacted the WPS to report the alleged assault. After experiencing some difficulty, the person was connected to the PSU and lodged the complaint.

However, PSU investigators did not follow up with the accuser and the IIU was not notified.

“It would appear that no investigation has been commenced. (The) IIU has not received any notification from the WPS respecting this formal complaint,” Tessler wrote.

Zane Tessler: To: Police Chief Danny Smyth

Re: REDACTED

Date: May 26, 2017

…It would appear that no investigation has been commenced. (The) IIU has not received any notification from the WPS respecting this formal complaint.

Once again, the accusation came to light outside the proper channels. If the IIU did not have direct contact with the accuser, it would not have found out about the allegation. It remains unclear how common such occurrences are.

The PSU reports directly to Smyth. No response from the chief turned up in any of the freedom of information documents obtained by the Free Press.

Institutional pushback and hiccups in the notification process are not unheard of during the early days of a police oversight agency, according to Ian. D. Scott, a lawyer and the former civilian director of Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit.

He said similar disputes were common after the SIU was formed in 1990, which helped feed the controversial reputation that dogged it for years and led to skepticism that the agency had any teeth.

During his time as head of the SIU, Scott pushed for legislative changes that gave the agency more power over the police departments that fell under its purview. He said similar reforms could come down the pipe for the IIU if there’s the political will to pursue them.

“The overarching issue is a lack of public confidence in policing. That leads to a lack of public confidence in civilian oversight of policing. I think those two things are linked,” Scott said.

“What you want is a seamless relationship between what the police do and what the public wants. When that breaks down, it’s a big issue, so you want to ensure there are strong oversight agencies in place.”

Questions of just how strong the IIU is, and what sort of oversight it wields over the WPS, are raised by a disagreement that broke out between the two agencies in August 2017.

On Aug. 10, Tessler reached out to Smyth to complain the WPS had once again failed to notify the IIU of an incident that fell under its mandate. This time, the chief responded.

The Free Press has obtained a copy of Smyth’s email. He asserted the WPS had done nothing wrong, since the IIU didn’t have the authority to investigate the incident at all.

In other words, the WPS refused to turn over the case. And so, the IIU never investigated it.

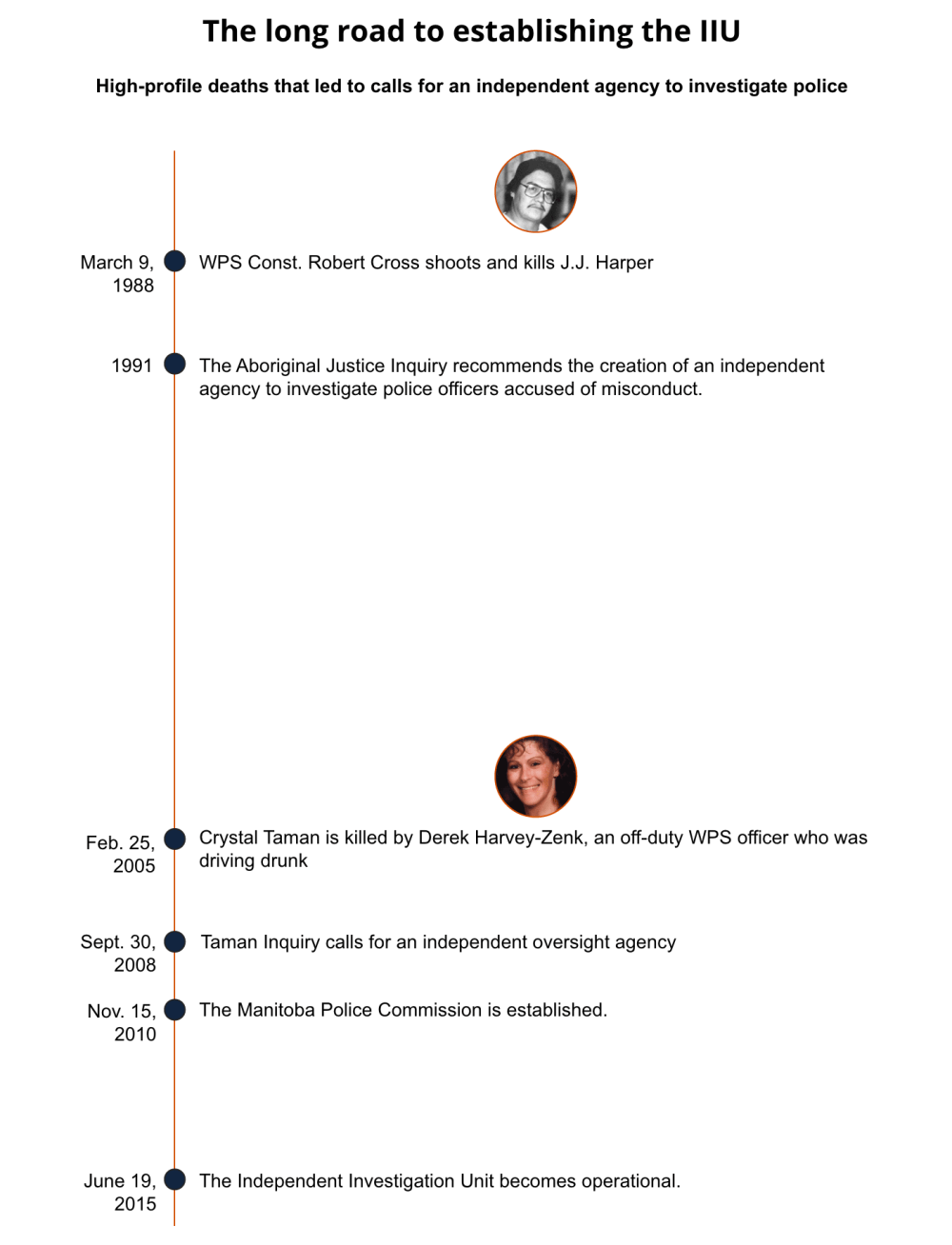

Early calls for the formation of the IIU can be traced back to the night of March 9, 1988 when WPS Const. Robert Cross shot and killed J.J. Harper, an unarmed Indigenous man walking alone in Winnipeg’s Weston neighbourhood.

Less than 24 hours after the shooting, then-Winnipeg Police chief Herb Stephen held a press conference to announce that Cross had been absolved of any wrongdoing.

However, significant media coverage, accusations of a coverup and an outcry from Indigenous groups eventually led to the creation of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry, which was formed — in part — to examine the fatal shooting and the way police dealt with it.

It was then, three decades ago, the idea of an independent police oversight agency was raised.

Calls for such a unit grew louder in the aftermath of the death of Crystal Taman, who was killed by an off-duty cop driving drunk in the cold, early morning hours of Feb. 25, 2005.

Following a night of partying with fellow officers, WPS Const. Derek Harvey-Zenk drove a pickup truck into the back of Taman’s car while she was stopped at a red light, minutes after she’d left home for work.

The 40-year-old mother of three was killed instantly. Photos from the crime scene show her small, yellow Chevrolet Sprint convertible crushed and crumpled in the middle of the road.

Due to a botched police investigation — which saw members of the now-disbanded East St. Paul Police Department accused of lying to protect a brother in blue — Harvey-Zenk got off with what many consider a slap on the wrist.

While he initially faced four charges, including refusing a breathalyzer and impaired driving causing death, a controversial plea bargain saw all charges dropped, except for dangerous driving causing death.

In return, he received a conditional sentence of two years house arrest.

The Taman Inquiry, which was established in the wake of the tragedy, called for a civilian unit to oversee investigations involving police. This time, the provincial government decided to act.

Crystal’s widower, Robert Taman, was named an original member of the Manitoba Police Commission, which was established Nov. 15, 2010, and helped guide the creation of the IIU. He was determined to see an end to the days of police investigating police.

In April 2016, less than a year after the IIU became operational, Taman resigned his post, due to growing concern over the agency’s direction.

“I left because I felt my involvement wasn’t going to help move this forward, and possibly by leaving it might bring some light to a very ugly situation,” he said.

Taman was concerned the culture of the “blue wall of silence” wasn’t being addressed and questioned whether the days of police investigating police had been put to an end or were just continuing under a different name.

Despite those growing concerns, even he was in the dark about the behaviour going on behind the scenes.

Taman was disturbed, but not surprised when shown the results of the Free Press investigation. At times, while reading internal IIU documents, he was at a loss for words.

During the last of two interviews for this project, with all the evidence laid out in front of him, Taman called for a full provincial audit of the IIU.

“Nothing has changed,” he said, shaking his head. “It’s like nothing has changed at all.”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

– Graphics and story presentation by Graeme Bruce; video by Mikaela MacKenzie; Icons by Simon Mettler, Paul Jackson, zidney and Vignesh Raja from the Noun Project

Ryan Thorpe

Reporter

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

History

Updated on Monday, November 19, 2018 9:00 AM CST: Minor changes; clarifies that IIU does not track statistics for charges laid in cases it monitors