The return home

Dauphin River First Nation restored six years after flood

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/06/2017 (2497 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

DAUPHIN RIVER FIRST NATION — It’s still a ghost town for now, albeit a shiny one, except for all the construction workers and tradespeople.

But residents of Dauphin River First Nation, who were forced to flee their community in 2011 because of flooding, will soon be able to return to 43 new homes relocated from the former Canadian Air Force base in Gypsumville.

Another six homes not from the airbase are still being built, and 19 more original homes will be part of Phase 2 of the community’s restoration process.

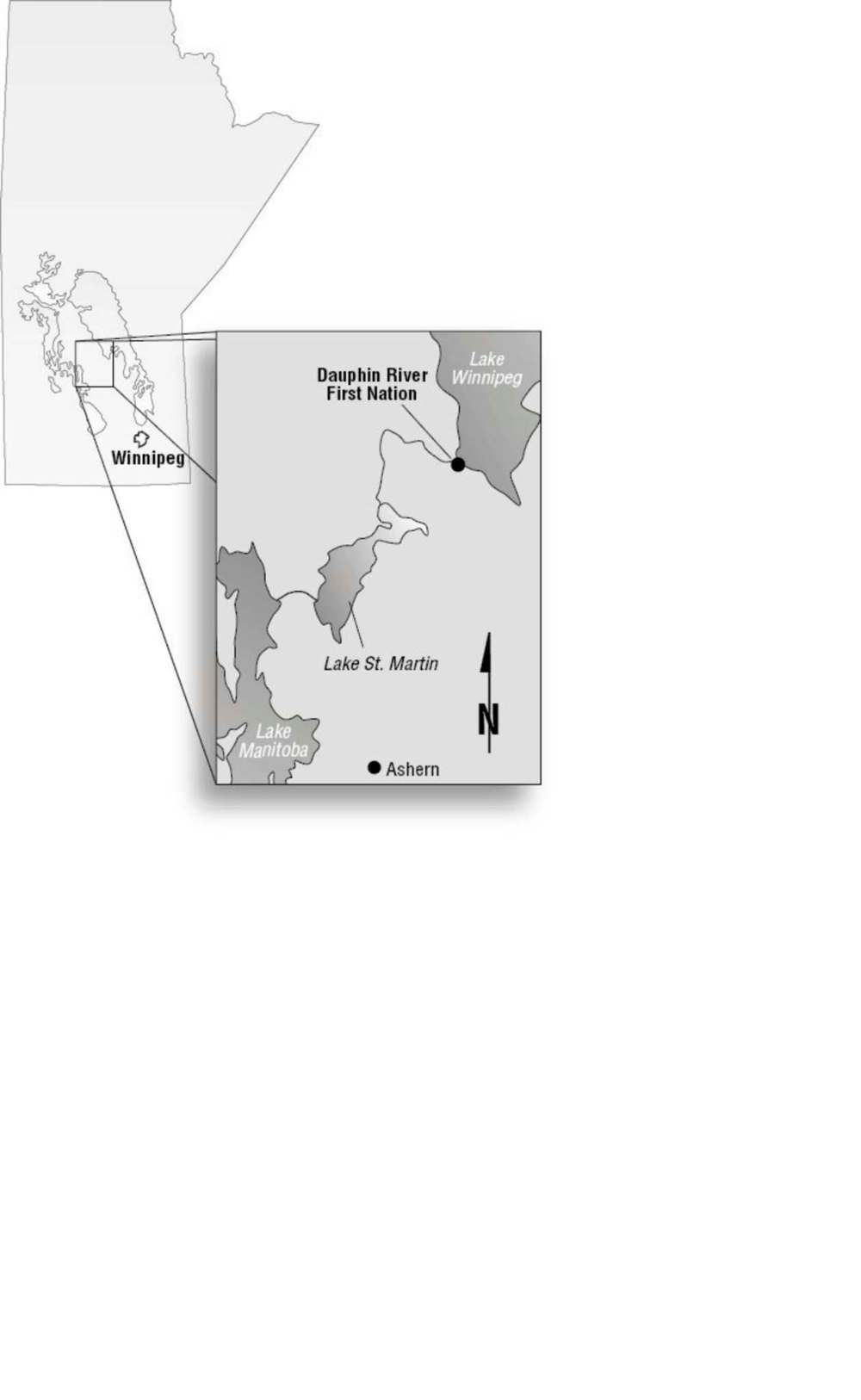

Dauphin River, located 250 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg, will also get its own water and sewage treatment plants, replacing well water and septic fields, quite a perk for a tiny populace of about 300 people. It is also receiving 1,800 additional acres of land.

“It’s a brand new community. You’re getting brand new infrastructure, a brand new school, a brand new office. I would say the ball is in our court as far as how we want to build our community,” said Emery Stagg, the housing co-ordinator for Dauphin River First Nation.

Most Manitobans can be forgiven for not knowing the story of Dauphin River First Nation or where it’s located. It’s been overshadowed by the much larger Lake St. Martin First Nation, which was also evacuated in the 2011 flood.

Dauphin River, the waterway the Ojibway reserve is named after, is nowhere near the City of Dauphin or Dauphin Lake but farther to the east. Dauphin River is the tail end of the controversial drainage of the Assiniboine River via the Portage Diversion and through Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin. The Dauphin River is the final leg of that relay race carrying water into Lake Winnipeg.

Dauphin River is also the name of the Métis village connected to it. The reserve and village are located where the Dauphin River empties into Lake Winnipeg.

The reserve is much further ahead in the rebuilding process than Lake St. Martin. But it’s also further behind. It was supposed to open last December. Then it was supposed to reopen this month. Now it’s not expected to be ready until sometime in August. There have been problems, including a fiasco where main sewer lines had to be installed three times. Yards still need to be landscaped.

The federal government has not released what the flood, evacuation and reconstruction have cost so far for bands such as Dauphin River.

Being away for six years is a long time, said Stagg. “I want to go home. I’m excited to go home. But nothing’s ever 100 per cent of what you had,” he cautioned.

Not everyone will return to the reserve once the federal government’s financial sponsorship of evacuees ends in August. Over the course of six years, some residents have died and some may have put down roots in Winnipeg. Some people’s children have grown up in Winnipeg and won’t want to leave.

As well, the Dauphin River School, also being rebuilt, only runs to Grade 8. Families with teenage children may opt not to return to the reserve so their kids can finish high school in Winnipeg.

Helgi Einarsson, mayor of the village of Dauphin River that is integrated with Dauphin River reserve, predicts 75 per cent of people will return and the rest will keep their new residences for weekends.

Einarsson, a commercial fish harvester, believes people will come back because it’s a strong commercial fishing community. About 20 band members have a quota to harvest fish commercially, including Einarsson, who also rents cabins and runs a fishing outfitting service. Every person with a quota usually hires two helpers, so that’s a significant proportion of the community.

However, local fish stocks have plummeted because of the increased flow from the province’s operation of the Portage Diversion, local fish harvesters say. The increased flow wiped out much of the pickerel spawn in 2011, 2012 and 2014, said Einarsson. That’s according to study for Manitoba Infrastructure by North South Consultants in Winnipeg, he said. The walleye spawn could be lost this year due to increased flow, too, he said.

The province did not return messages about the fish stocks. The province is consulting with local fish harvesters about how to avoid future spawning losses.

“Losing a couple years of spawn has kind of screwed things up,” said Billy Pierce, who runs the Dauphin River Fisheries, which collects the local fish catch for the Manitoba Freshwater Fish Marketing Board.

Emery Stagg’s brother, Norman Stagg, estimated only about a dozen commercial fish harvesters bothered to put their nets in this spring. That’s out of the 63 who hold quota in Dauphin River, Little Saskatchewan, Lake St. Martin and the town of Gypsumville, and who fish in Sturgeon Bay on Lake Winnipeg.

The artificial flooding by the Portage Diversion has also littered the river with trees and other debris, destroying many fishing nets.

Emery Stagg scoffs at any assertion the federal government is overbuilding Dauphin River.

“There’s always a housing backlog in First Nations across Canada. We’ll never fulfil that dream of housing for First Nations across Canada,” he said.

“It’s been a long six years, but we can see the light at the end of the tunnel, and I hope it’s not a train,” he said with a laugh.

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca