Tangled roots

Clients find hope in city treatment program that digs up long-buried childhood trauma, family dysfunction to understand, attack adult addictions

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/10/2017 (2377 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

There was no good reason for Kim Thorarinson to walk into the liquor store on that crisp January day. No good reason, she thought later: it was just a habit, something she knew how to do every day.

Now, sitting in a detox centre one week later, Thorarinson thought about how it had all fallen apart.

She’d held it together for so long. But then she was downtown for a work convention; during a lunch break, she headed to the dollar store. Along the way, she passed a liquor mart, and that familiar draw rose up inside her.

She walked in, bought a bottle of vodka, and drank it right there and then.

When she got back to the convention, her boss took her keys and sent her home. And Thorarinson loved her job: she’d thrown herself into mastering it, and it was working. Her boss always sought her ideas and opinions.

“All I’d ever wanted is for someone to give me a chance,” she says. “That’s what he did. And I just shat all over it. Why? Because I walked past it. That’s a really bad reason. That was eye-opening, that this needs fixing now.”

If you’d asked her before January, she says, she would have sworn she’d never quit. At 35, she couldn’t remember a day when she hadn’t had at least a few drinks, pounding them back before her morning coffee.

Her dad drank, too; when he was 40, doctors told him that if he didn’t quit drinking, he would die. Three years later, he died from cirrhosis of the liver. Thorarinson was 11 years old at the time. The loss shook her world.

Once she was old enough, she started running. To the Bahamas, to Europe, where she met the father of her two bright tween daughters. And as she sat in detox, she began to realize: booze was another way of running, too.

“The fact that everyone else seems to deal with life better, you just don’t get it,” she says. “You don’t get it, because you never learned it… I didn’t want to be inside my head, at all. It was a very scary place.”

She hoped to get a bed at the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba’s 21-day residential treatment program; they could admit her in six weeks, they said. But six weeks, for an addict on the tipping point, is a very long time.

But then she spied a poster at the detox centre, among the leaflets for local rehabs and Alcoholics Anonymous.

Someone — Thorarinson has never found out who — had handwritten it in blue with a Sharpie. It was simple and heartfelt: the poster-maker wrote about how a new, community program called Re:Act had worked for them.

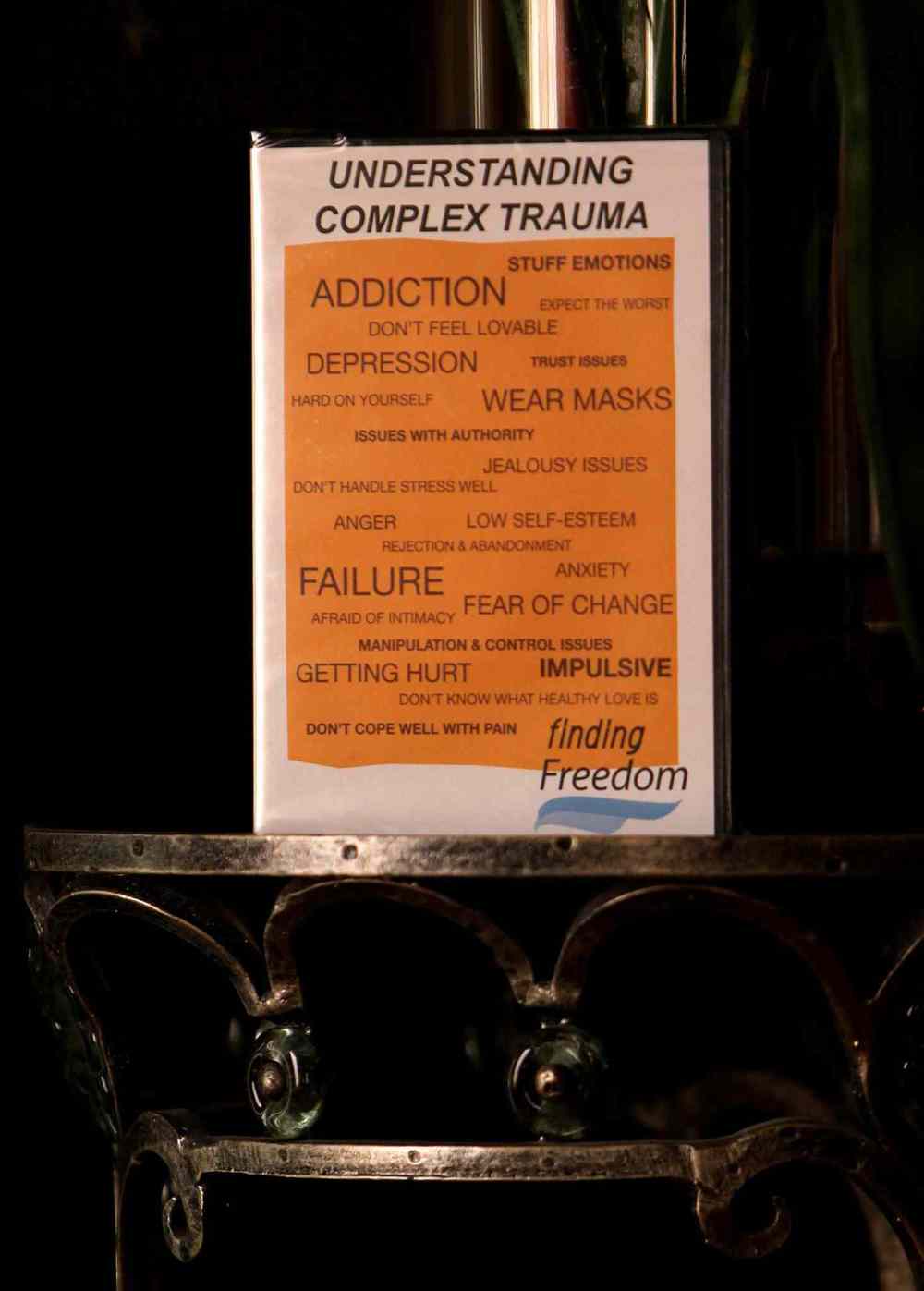

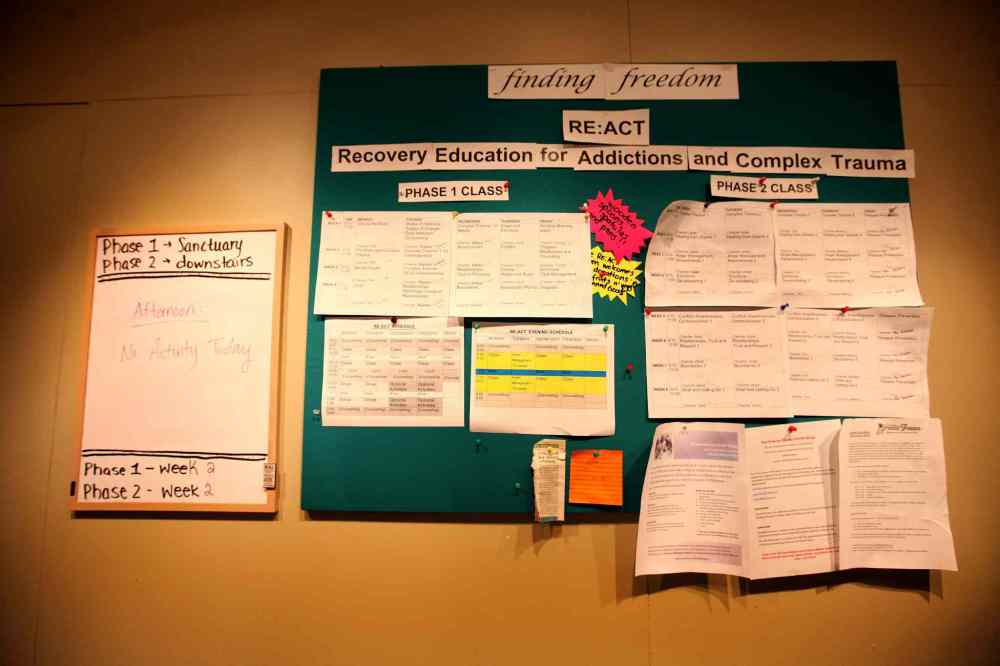

Thorarinson read what the acronym stood for: Recovery Education for Addictions and Complex Trauma.

“That the missing piece,” she thought, and within days she had emailed the program, looking to get in.

● ● ●

When we talk about many public burdens — health-care funding, justice-system funding, crime — we are also talking about addictions. They are the root of many of the social and economic costs communities are forced to bear.

And when we talk about addictions, we are really talking about people. Regular people, caught in a cycle they fight to escape, trying to get by. Even addicts, in the grips of their addiction, don’t always understand why.

To effectively treat addiction, you have to know where to start. Perhaps the spark lies in an obvious, but difficult, question: why do some people become addicts, but not others? What is the difference between them?

Specialists have studied this problem for decades, trying to understand the causes and triggers. For a while, many pointed to the drugs themselves; heroin, for example, is known to be powerfully addictive.

Yet the majority of people who try heroin do not become addicts. The same goes for other types of drugs.

Brain chemistry, then? What about adult trauma? Research shows they may play a role, but they don’t solve the whole puzzle. Because some addicts, in some situations, comfortably walk away where others stay stuck.

During the waning days of the Vietnam War, Americans were shocked to learn that as many as 40 per cent of U.S. soldiers had tried heroin while they were deployed, and an estimated 20 per cent of them were actively addicted.

But something remarkable happened when they came home: most of them quit. Of the addicted soldiers, only five per cent relapsed after they were back in the United States. The remaining 95 per cent got, and stayed, clean.

Meanwhile, civilians in the U.S. who become addicted to heroin have a notoriously high relapse rate, about 90 per cent. So what’s the difference? Answer that question, and maybe you can unlock the gate that offers a way out.

In the meantime, the cycle rolls onward. People with addictions try to hang on. Families fumble through.

● ● ●

In 2012, Tim Fletcher invited 20 people to breakfast. They were all addictions support workers, and met to float ideas for a new program; they’d come to believe that available options weren’t meeting Manitobans’ needs.

Fletcher had never wrestled with addiction, but he empathized with addicts: when he was 32, he was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome. It devoured his energy, rendering him nearly absent from his three kids.

“I was kind of brought against my will into the world of dysfunction,” he says with a chuckle.

By then, Fletcher had, settled in Manitoba. Originally from Simcoe, Ont., he’d worked for General Motors before starting a small church. In 1988, he came to Winnipeg to work as a pastor at Charleswood Community Church.

After 10 years there, he was physically and mentally burned out. He took a two-year stint on disability, and then worked on nearby farms. In 2003, a friend approached him about a job at Tamarack, a West Broadway residential rehab facility.

“We really need a male counsellor, and I think you would be good for it,” she told him.

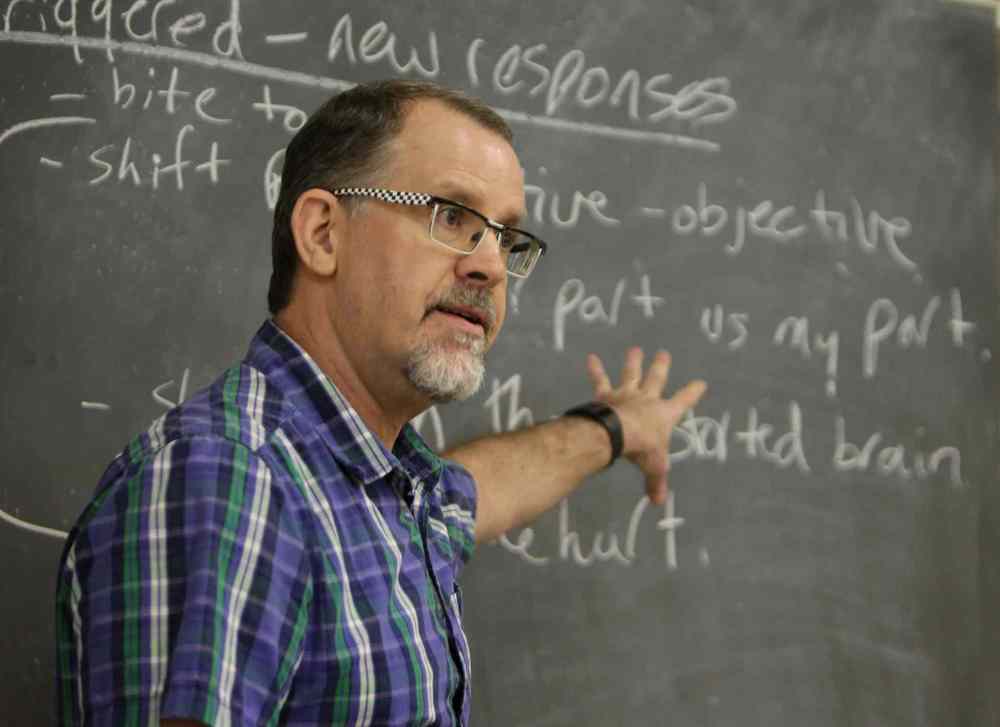

Fletcher was good at counselling, as it turned out. He is lanky, with a tidy grey goatee and one of those faces that always seems slightly bemused; clients at Tamarack found it easy to open up to him, and he liked them, too.

“What I loved about working with addicts who wanted help is there’s a level of honesty,” Fletcher says. “They didn’t want superficial. They wanted to talk real, and they wanted to understand why they did what they did.”

As the years at Tamarack turned, Fletcher noticed some common threads in his clients, even when they shared few traits on the surface. Virtually all of them had grown up with family dysfunction or childhood trauma.

What that meant, Fletcher thought, is that many addicts reached adulthood with little understanding of healthy behaviour. They didn’t know how to cope with stress. They struggled to differentiate good relationships from bad.

“They have ideas of what (healthy) looks like, but they’ve never seen it,” he says. “Sadly, what happens at most treatment centres, is they (the groups) drift towards becoming unhealthy families, because that’s all they know.”

In 2008, Vancouver physician Gabor Mate released a book, In The Realm Of Hungry Ghosts, that detailed his experiences treating addicts at a harm-reduction clinic in the city’s blighted and struggling Downtown Eastside.

Through that work, Mate drew the same conclusion as Fletcher: all addictions, he believed, stemmed from complex trauma. That was a big part of the answer as to why some people became addicts and others did not.

The book was a bestseller, and Mate’s compassionate approach to treating people won him many admirers.

His beliefs have also been criticized by many psychologists and addictions specialists. (The content of those critiques is too detailed to document fully here; in short, many say Mate’s theory does not line up with data.)

But the childhood trauma strikes a deep chord with many addicts, who see the blueprint of their own lives.

There’s little question that available treatment options have highly variable success. And navigating treatment in Manitoba can be a frustrating, confusing process for addicts and their desperate families.

Private programs can be pricey. The public system is overburdened; many who ask for help wait for weeks or months for beds. Outside of residential facilities, there is a determined patchwork of community programs.

What if, Fletcher thought, they could start a new program that helped people work through what he believes are the underpinnings of addiction: the shame and fragile coping mechanisms originating in childhood trauma?

Fletcher had already co-founded Finding Freedom, a support meeting based around the idea that addiction was a symptom of deeper, older problems. So the next step was spinning off that approach into something larger.

In 2016, Fletcher left Tamarack, and that October he opened the doors to Re:Act. It would be an open-ended day program; clients went home at night, back to their regular lives. The program wouldn’t cost them a dime.

If all went well, Fletcher believed, it could give some addicts the hope they searched for.

● ● ●

The heart of Re:Act is Place of Grace, an unassuming brick-and-stucco church just a few blocks north of Nairn Avenue. Five days a week, as many as 40 people come here to work through various levels of the program.

On this morning, clients file into their session just after nine o’clock. Already, the place smells inviting — Re:Act’s cook is whipping up pea soup for lunch. After a few minutes of friendly chatter, they settle down to work.

Today’s subject is “shame,” and how that can play into relapse. On a chalkboard, Fletcher sketches a branching road, a little like a “Y” lying on its side. This fork in the road, Fletcher explains, is where they are standing.

Choose the road of change, and it’s full of fear and pain. But the other road only goes one place: relapse.

“Every good addict goes, ‘I wonder if there’s a third road there?’” Fletcher says.

The room ripples with laughter. They’ve all shuffled between those roads, in one way or another.

There are a dozen clients here today; they include Lynn, a 33-year-old mother whose life suddenly collapsed into a mess of methamphetamine; and Douglas, a 47-year-old who has struggled with alcohol for more than 33 years.

These are Phase 2 clients. They’ve already gone through Re:Act’s first stage, an emotionally gruelling four-week introduction. Most clients who drop out of Re:Act — or relapse — do so during that first month.

Kim Thorarinson, who is now a graduate of the program, originally thought she might go back to work after finishing Phase 1. But those first weeks in Re:Act opened her eyes to the long road ahead, she says.

“I was so raw, and so vulnerable, that by the time the four weeks was done, I was not ready to go back to work,” she says. “I was just starting to come to terms with what caused all of this in the beginning.”

The program isn’t always so draining. In the afternoon, clients take time away from the emotional work, and sign up for activities such as guitar lessons. (They’re organizing a group to go bowling this day.)

Some of the friendships they make along the way would otherwise be unlikely. People come to Re:Act from all backgrounds, all ages; they include business administration workers, sex workers, stay-at-home parents.

Some sign up to fulfil the requirements of their probation. Others bounced around residential treatment programs and 12-step support groups for years, trying to piece together sobriety from anything they could find.

But others, including Lynn, are first-timers. When her addiction hit less than two years ago, it was caustic and sudden: an acquaintance introduced her to methamphetamine, and within weeks she was using every day.

After a stint in detox, she enrolled in Re:Act. It allowed her to go home at night, and start to rebuild her life with her husband and children. That was half the battle, she said: changing how she reacted to everyday stresses.

“I’ve learned more about myself here than I have in my entire 33 years,” she says. “The knowledge you come out of here with is so freeing.”

In the first year, 159 clients arrived at Re:Act. Of that number, 45 completed Phase 2 — the third phase is open-ended — and program files show that all but five of those grads are clean today, and still actively involved in recovery.

Granted, it’s still early. The program is just a year old. But all of the graduates the Free Press spoke to described a new optimism for the future, one they hadn’t felt in previous attempts to stay clean or sober.

Lynn has already invited her best friend to her Re:Act graduation in November. Douglas, who is newly married, hasn’t had a drink in more than 50 days. (He combines his Re:Act study with regular trips to Alcoholics Anonymous.)

“I need this in my life,” Douglas says, simply. “It was a necessity.”

So positive are Re:Act grads about the program, that many now volunteer their time to help spread the word.

“I just want this place to flourish,” says T.C., who started Re:Act in its very first week. “This is such a huge program for people. It’s so amazing.”

Despite their vocal loyalty, nobody involved in Re:Act speaks of it as a miracle cure. Lynn and Douglas suffered relapses as they worked through the program. But they got sober again, and came back.

“I was just scared, because you do have to put your walls down,” Lynn says, of her early relapses. “But I always felt like the door was wide open. I always felt like I could come back, start from scratch, and get ‘er done.”

•••

Today, sipping a latte at a Polo Park coffee shop, Thorarinson is beaming. She is now almost nine months sober, and she’s taken up kickboxing. She returned to work, where she is once again thriving; her life is well on track.

“I guarantee you, if it hadn’t been for Re:Act, I’d be drinking right now,” she says.

Her daughters see the change in their mother: life seems easier for her now, they say, and she’s happier. There are still difficult days, Thorarinson agrees, and maybe there always will be. It’s just that now, they don’t sink her.

And when she feels the need, she calls up some of her friends from Re:Act, to laugh or just listen.

“We’re told our whole lives, ‘it’s in the past, get over it,’” Thorarinson says. “So then you bury it, you cover it. You drink it away, you just get rid of the feelings. (Through Re:Act), you start to realize that your feelings are OK.

“If you don’t have the right people in your life, find new people,” she adds. “Life and connections are key. Re:Act is the place where you realize we all need each other… those connections are absolutely vital to your survival.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large (currently on leave)

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

History

Updated on Saturday, October 21, 2017 10:42 AM CDT: Thorarinson did not suffer a relapse.