The final witnesses They are the last among those who lived through the cruel infamy of the 20th century and want their experiences to serve as a warning

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/01/2018 (2294 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

More than 70 years later, Sonia Kushliak becomes emotional when she remembers eating part of a loaf of bread.

Kushliak is one of millions of Ukrainians who survived what is known as the Holodomor, the Stalin-era Soviet Union famine that killed millions in 1932-33.

Her father had been put in jail and was out helping construct a public dock on a river in a town three kilometres away. He was given a ration of soup and part of a loaf of bread for lunch every day; he would eat the soup and save the bread.

His daughter walked the six kilometres each day to pick up the bread and take it back home for the rest of her family.

“I remember once I was so hungry I tore off little pieces of bread and ate them on the way home,” she said, tears beginning to well up.

“By the time I reached home there was little left. My mother wasn’t angry, but I’ve felt guilty ever since. I can’t even think about it without crying. We shared equally the bread. Everyone had been waiting for a piece of that bread.

“I didn’t do it again.”

Kushliak didn’t read about the Holodomor in a history book. She didn’t learn about it on a website.

She was there.

She felt the emptiness in her stomach that led her to eat a bit of bread before she realized it meant the other members of her family would do without that day.

Her eyes were witness to the genocide. Those now-93-year-old eyes will one day close for a final time.

There are, of course, fewer survivors’ eyes with each passing year. People such as Kushliak, who lived through one of the 20th century’s atrocities, are disappearing from our midst. It’s akin to the soldiers who fought in the First World War — the last one died in 2012 at the age of 110. Some time in the next decade or so, it will be the same for Canadian veterans of the Second World War — their average age is about 94.

The Armenian Genocide was the first of the last century’s atrocities and saw the Ottoman government kill as many as 1.5 million of the two million Armenians between 1915 and 1917.

There are only a couple of dozen people alive today who lived through that time, but they were babies or very young children. The last Canadian survivor died last year at 107 years of age; she was six when her family went into hiding.

But the decades to come saw more evil perpetrated on a massive scale, and those who somehow managed to survive — the Holodomor, the Holocaust’s Nazi death machine and other atrocities, such as Second World War Japanese prisoner of war camps or, during the same period at home, Japanese-Canadians stripped of property and sent to work camps or sugar beet farms — experienced some of mankind’s most glaring inhumanity.

They were traumatized children and youths whose lives were irrevocably changed because a soldier, a leader, a country, decided to unleash pain and suffering on others. There are likely a few who live with trauma of a different sort; perhaps they — or their family members — were among the people meting out the cruelty.

And there are some who saw what was happening to neighbours and friends and chose to do nothing.

The one thing they all have in common is their age and the stark reality that their lives are drawing to a close. But most of the dwindling number left still remember; there are some things even the most forgetful seniors cannot wipe away.

They are willing to give voice to their pain because they want their stories documented to educate future generations. It’s why, before these last few pass on, historians and family members are hard at work capturing these memories while they can.

● ● ●

The Holocaust

Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, which invaded and occupied a vast portion of Europe during the Second World War, purposefully and systematically murdered six million of the continent’s estimated 10.5 million Jews.

Barbara Goszer, now 87, is a survivor because of her parents and a gentile family. She was 15 at war’s end.

Goszer was born in Lwow, Poland — Lviv, Ukraine since the end of the war — and she says her early childhood was “idyllic.” Her name then was Bronia Goldfischer and she went to Hebrew school, had piano lessons and danced. Her father was an importer and exporter of fabric, she had a stay-at-home mother and was close to her older sister Tonia.

“We were happy and secure in every sense of the word,” she says, adding that life was relatively unchanged during the first two years of the Soviet occupation. Then the German army attacked.

She witnessed “massacre after massacre, including the brutal murder of five people, a baby among them.”

Her family was incarcerated in the Lwow ghetto which, at its peak, had a population of about 200,000. The Germans emptied the ghetto in 1943, sending everyone inside to their deaths at extermination and concentration camps.

But before that, in August 1942, her sister, then 18, was taken away to the Belzec concentration camp where the Nazis were testing Zyklon B in the gas chambers, a key part of Hitler’s “Final Solution.”

“No one came back from there,” Goszer says.

Her terrified, grieving parents decided to try to save her by putting her life in the hands of the Stoklosa family, who were Catholics, that November. She became Halina Stoklosa.

By the end of the winter she had lost contact with her parents. She tried but failed to find them and other relatives after the Soviet army liberated Nisko, Poland in 1944, where the Stoklosa family had relocated. She later was connected to a Jewish community program in Germany created to help orphaned children. She arrived in Canada on a ship with about 150 other orphans in 1947, and was placed with a family in Winnipeg in 1948.

Goszer has lived here ever since, marrying her husband Adam Goszer in 1952, operating Adam’s Camera with him at Portage and Main from 1959 to 1987, and raising three children, one of whom died when she was five.

“I stayed with the Polish family for the duration,” she says. “That’s how I survived.”

Goszer says she doesn’t even know why she ended up being with the Stoklosa family.

“I don’t know if they were friends of my parents,” she says.

“I was 12 when I joined them. The funny thing is I looked like them. I had blond hair and blue eyes. If you looked at the mother, you could see I looked like them.”

Before that, to protect her, Goszer’s parents hid her whenever they left their home after the Nazis attacked Lwow.

“I had to stay on a shelf above the toilet. I had to be quiet or the neighbours could call you out.”

But there were times she did go out and that’s when she saw the brutality of the Nazis.

“What I remember I’d like to forget, but I can’t forget,” she says.

“One day, it was a gorgeous day, there was an old prison. I had to pass this place loaded with people and loaded with Germans with guns. I was 11 and wondered, ‘Do I just run by, or do I stop and watch?’

“There was a pregnant mother with three children. I watched as all of them were murdered. I walked away. I went home. There was a piece of furniture and I crawled in and didn’t come out until my parents came home.

“Once you saw what they could do… what kind of people were they?”

Goszer says her family was then moved into the ghetto, in “the worst part of the city,” before she ended up with the Stoklosas.

And although the pain of losing her entire family and the memories of the brutality she witnessed, Goszer considers herself lucky.

“I wasn’t in a camp. I lived with nice people, even though they had to hide me. They would have got the same bullet as me had I been found out,” she says. “I was so young (that) it was not the nightmare it was for people that had been established and then lost everything.”

Alive, but alone.

“It was a war that continued after the war,” she says. “You throw all the people out to different countries and you had to find your niche. It was hard. But it still might have been better, since I was a kid.”

Many times while raising her own family, Goszer wondered what became of the Stoklosas.

“When I was leaving, (the mother) said I have a home — “why are you going?” I said I am the only one, but I will stay a Jew.

“I kept in touch with them for a while, but then we lost touch. But it always stayed with me. How do we reconnect?”

After telling her story to a Holocaust museum in Los Angeles, she didn’t know it, but members of the Stoklosas saw it, but didn’t know where she was living.

“One day I got a phone call. ‘Are you Halina Stoklosa?’ I said ‘yes’ and I started to tremble. It wasn’t good news, but it wasn’t bad, too. The woman said the mother was gone long before, but her sons and daughters wanted to contact me. The oldest daughter was gone too, and my so-called brother was gone too, but the rest lived in Poland.”

Goszer says there’s something else she has always wondered about since the war ended — what did the Nazis who forced Jews out of their homes, brutalized them in the ghetto and exterminated them in the camps tell their own families”

“What did they tell their sons and daughters? That they killed people? I also think, ‘how did I survive?’ I have no answers.”

Goszer says she and other Jews around the world realized years ago that they had to document what they went through for future generations.

She says it’s why she pushed for the creation of the Freeman Family Holocaust Education Centre at the Asper Jewish Community Campus and served as its first chairwoman.

“They were building the centre (that opened in 1997) and I moved heaven and earth to make sure they put a Holocaust Education Centre there,” she says.

“We knew we would age and someday no one would be around to speak for us.”

Goszer says it was her daughter who made her realize the effects of the Holocaust were still with her decades later when she realized how protective she was of her children.

“She would play outside and she took care of her brother three years younger. But I always wanted to be out there and she noticed it. She said, ‘Mom, you are always in the window.’

“It lives with you forever.”

● ● ●

Japanese internment

Art Miki was living with his parents and grandparents on his grandfather’s strawberry farm in British Columbia on Dec. 8, 1941, when Japanese troops attacked nearly 2,000 Canadians defending Hong Kong — Winnipeg Grenadiers and Quebec City’s Royal Rifles of Canada — just six hours after hundreds of Japanese aircraft launched a massive surprise assault on Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor.

Canada and the United States were now participants in the Second World War, bringing upheaval and uncertainty to well-established Japanese populations along the Pacific Coast in both countries.

Miki’s life would never be the same.

The community of Haney is now part of Maple Ridge in the metro Vancouver area. About a third of the region’s early settlers were Japanese. While many worked at the factories, logging camps or on fishing boats, there were some — such as Miki’s family — who owned local fruit farms. One of his grandfathers immigrated to B.C. in 1892, the other arrived in 1903.

By the time the war broke out, Miki was living with his parents in a house on the strawberry farm property his mother’s father had owned since 1918.

“I had just started kindergarten. I was five years old at the time,” the now-80 year old says.

“There was a shortage of labour here so the Manitoba Sugar Beet plant had permission from the Manitoba government to take farm workers. So instead of going to an internment camp, you could go to a sugar beet farm.”

Miki didn’t know about it at the time, but a few investors had joined together after the war began in Europe to build a sugar-processing plant in south Winnipeg, requiring sugar-beet growers. With so many young, able-bodied men off fighting the war, there was a shortage of farm workers.

Miki says his family chose to work on a farm, but not because they grew strawberries in B.C.

“They were told the families would be kept together,” he says. “At internment camps males would be taken to camps to work on roads. This wouldn’t happen to us.”

Miki’s family arrived in Manitoba by train in May 1942. They were part of the second of three groups of Japanese people recruited to work on sugar beet farms. A total of 1,075 would end in the province.

Miki says they were taken to work in Ste. Agathe, where his family and two others lived in a four-room farmhouse. There were seven adults and three children before his brother was born.

“There was no insulation, water or electricity,” he says. “My grandparents, parents and a friend of my grandfather lived there.”

Miki doesn’t remember much about his time on the farm, but he knows how it hurt his family.

“All I remember is an open field that never ended,” he says.“There was no insulation, water or electricity… All I remember is an open field that never ended.” –Art Miki

“Sugar-beet work is very hard work and my grandparents were 60 at the time.”

Two years later, Miki’s dad received authorization to work as a machinist in Winnipeg, so the family moved to North Kildonan — then a separate community — because unlike Winnipeg, Japanese-Canadians were allowed to live there without getting special permission. He said about 10 Japanese families made the same move.

Miki says his grandfather suffered at having to do back-breaking work at an age when he should have been thinking about retirement. What made it worse was losing the strawberry farm he had worked so hard to build.

“My grandfather sold the farm before we left B.C. They were told they would not be going back there. It was suggested they sell it instead of the government taking it. But he sold a seven-acre farm for $2,000… he passed away shortly after the move to North Kildonan and I believe he died a broken man because he had little to give to his family and grandchildren.”

Japanese were again permitted to own property in the country after the war. Miki’s family moved to a house on Alexander Avenue in Winnipeg rather than return to the West Coast.

“My parents just stayed here because it was their home now,” he says, noting they’d been here seven years at that point. “They would have had to start a new life again there. They also had close friends here.”

Miki became a school teacher and principal and served as president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians, which fought for a formal apology from the Canadian government and compensation for seized property.

Prime minister Brian Mulroney’s government agreed in 1988 to formally apologize to Japanese Canadians for what happened to them during the war, pay each survivor $21,000, put $12 million into a community fund and create a Canadian Race Relations Foundation.

On a visit to Vancouver, Miki found a high-end housing development where his family once grew strawberries. He was told that when builders were excavating the property, they found remnants of farm.

“The whole property was all tilled for drainage. Someone did a lot of work to get that land ready. They also found old medicine bottles from Japan.”

The only thing the family has from their lives there is a set of dolls his grandmother brought to Manitoba.

“They are given to you when you are born,” he says. “I discovered it many years later, locked in a trunk.”

Japanese were allowed to take just 75 pounds of possessions with them when they were uprooted, he says.

“I often wonder, ‘Why did my grandmother bring a doll?’ But people brought things important to them.”

The local Japanese community is working to preserve the memory of wartime indignities and hardships.

“The younger generation doesn’t know,” he says. “Even during the redress movement… very few of the young people didn’t know why they were living in Winnipeg. They just thought their parents had moved here.

“The children would also say, ‘Why didn’t you do something?’ But you couldn’t, they couldn’t even vote.

“I often think, ‘Had the Japanese had the right to vote, maybe this wouldn’t have happened.’ When you don’t have the franchise you don’t have the same equal status.”

● ● ●

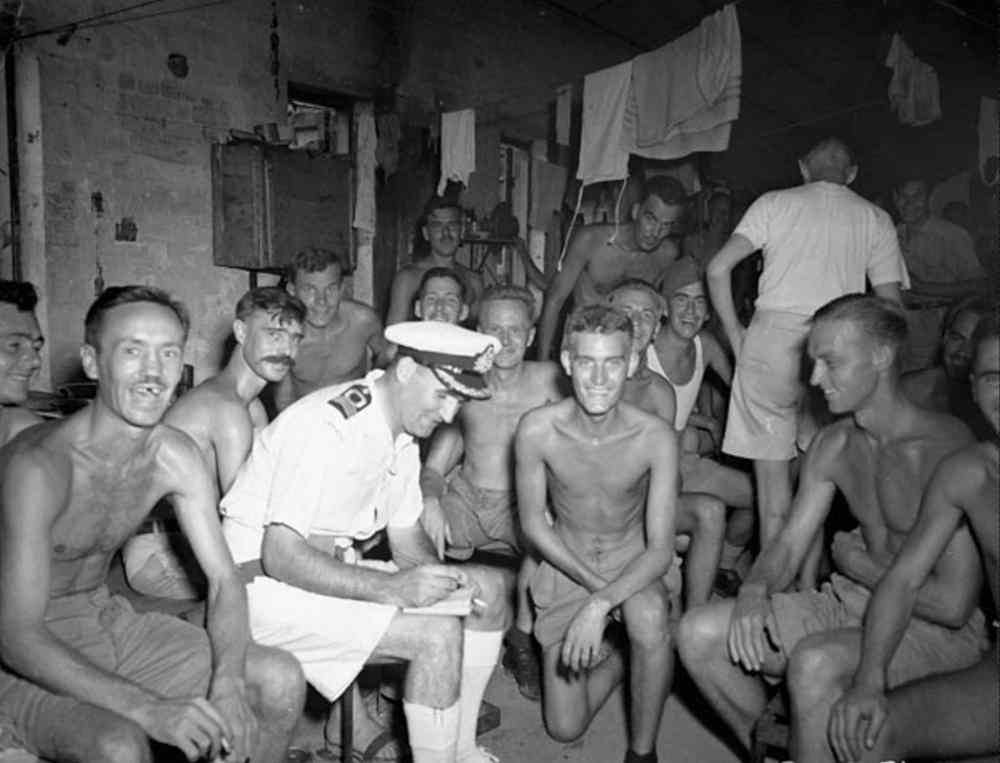

Prisoners of war

There are some stories George Peterson will take to the grave. They are too troubling personally to share.

But his story and that of the Winnipeg Grenadiers in the Second World War needs to be widely told. As the last surviving prisoner of war from the Grenadiers’ Battle of Hong Kong, it’s a responsibility that rests with him.

He’s sitting in a hospital chair when he recites by memory four numbers: three, eight, two and one. Three years, eight months, two weeks and one day; the length of time he was a PoW.

Peterson is recovering from a couple of broken bones in his foot at a Winnipeg hospital. But his bones aren’t really what’s keeping him in hospital at this point; it’s the painful residue of his time in a Second World War prison camp, where he developed beriberi.

Rubbing his fingers, he explains the disease caused by not getting enough vitamin B-1 — thiamine — something that occurs when you eat only thiamine-deficient food such as white rice.

“It’s in both feet and these fingers,” he says. “The nerves were damaged.”

Peterson, now 96, was a 20-year-old corporal, one of 915 officers and troops with the Winnipeg Grenadiers who boarded a train in Winnipeg bound for Vancouver in October 1941. They were joined by hundreds of members of the Royal Rifles of Canada and officers and troops attached to Brigade Headquarters, and soon boarded a ship to take them to Hong Kong.

Just hours after the Dec. 7 assault on Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces attacked, beginning the Battle of Hong Kong, in which the Canadians were badly outnumbered. Their valiant effort ended in surrender two weeks later, on Christmas Day. Peterson and hundreds of others spent the remainder of the war years in a daily struggle to survive inside a PoW camp.

Of the 1,977 Canadian soldiers who saw action in Hong Kong, Peterson is one of a handful of remaining survivors 76 years later.

“There are only 16 of us left today; 555 men would never return to Canada,” he says. “And I’m the sole survivor of the 915 Winnipeg Grenadiers who went.”

Peterson was taking a physical education course when the Japanese air force began dropping bombs on Hong Kong. The first wave of Japanese troops came ashore days later; Peterson was one of hundreds of soldiers trying to prevent them from overrunning the colony.

One of his orders was to take some troops to a police station and “to guard it at all costs.” Thankfully, he says, a major saw them before the troops moved out and asked what were they doing.

“When I told him, he said, ‘Bulls—, if one falls back we all fall back.’ I was glad to hear that.”

The Battle of Hong Kong was the first major action of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, with hundreds of Winnipeggers involved.

“We were the first in and the last ones out,” Peterson says.

Japan captured about 140,000 Allied soldiers during the war and took about 36,000 back to their country to work as labourers. Peterson said he was one of many taken to the prisoner camp in Sendai on the Japanese mainland to work in a coal mine.

“We didn’t live. We survived on hope,” he says. “We were taken prisoners of war on Christmas Day and we thought we would be out by Easter. Easter came, and then we thought Victoria Day. We didn’t dare put the date too far ahead.

“We were there for three years, eight months, two weeks and one day.”

Coal mining was tough, not only for men who had never worked as miners before, but because of the conditions and the daily quota their Japanese captors insisted they extract.

“We had two shifts, one was a Canadian shift and the other was Portuguese from a Portuguese regiment, which had been in Hong Kong,” he says. “Our quota each day was 14 tons. The Portuguese went to the Japanese and said the Canadians were all labourers and used to hard labour, where the Portuguese were all office workers and shouldn’t have the same quota as the Canadians.

“The Japanese agreed. But instead of cutting they added two more tons to our quota.”

Then in August 1945, while working in the mines, they were told to surface. That’s when they learned the war was over.

The front page of the Free Press on Sept. 27, 1945 features an article and a photograph of a smiling Peterson, and his twin brother Morris, as they arrived in Vancouver following their liberation.

“There will be double cause for celebration in the Peterson home at St. Vital Sunday night,” the article stated. “That’s when the twins, Cpl. George and Pvt. M. Peterson, of the Grenadiers, are scheduled to arrive.”

The article went on to quote the smiling pair as saying, “We always do things together, even to getting captured by the Japs.”“There are still some things I saw that I won’t talk about. Especially when I’m asked how many people I killed. I say that’s between them and me.”–George Peterson

A few days later, an Oct. 2 article told how their parents rushed out of a special waiting room at the CP Station on Higgins Avenue to give each of their sons a corsage as well as “a happy confusion of hugs, kisses and hand clasps.”

Morris died of cancer shortly after turning 65, Peterson says — “He wanted to get his old-age pension.”

Peterson said there were two occasions overseas when his fate hung in the balance.

The first was when the troops surrendered. He wanted to commit suicide, which he had vowed to do if ever taken by the enemy.

“I tried, but I couldn’t pull the trigger,” he says. “A girl at a party in Winnipeg had asked me what would happen if I was taken prisoner, and I said I’d rather commit suicide than be taken prisoner. But I couldn’t do it.”

The second was his incapacitation, preventing him from joining an escape attempt.

“I had dysentery and malaria at the same time — but it saved my life,” he says. “A very good friend of mine tried to escape. Three others went with him, but the Chinese boatman they hired turned them in for the reward the Japanese offered.

“All we know is they were captured, tortured and killed. Their graves were never found. I would have been with him if I hadn’t been sick. He was a very good friend of mine, so I would have gone with him.”

Thanks to the American forces air-drops, Peterson and his brethren had been eating plenty of food in the weeks before they left Japan, and they quickly gained back much of the weight they had lost while being interred. That made it difficult to convince people back home of the hardships they endured.

“We were still in the camps on Aug. 15, 1945, and we weren’t released from our camp until Sept. 9,” he says. “We were eating everything and anything we could get our hands on.

“The lowest I got was 80 pounds — I had malaria at the same time. I was usually 140 to 150 pounds… it’s funny because on Sept. 9 we spent the night on a U.S. hospital ship and when we asked for a second helping of food they said no, it would make us sick. But we had been eating.

“When I arrived home I had put on 68 pounds in six weeks.”

One of the main reasons he and others formed the Hong Kong Veterans Association was so they could get the word out about what happened to them and have meetings where fellow veterans could meet and talk about what they had been through, he says.

“There are still some things I saw that I won’t talk about,” he says. “Especially when I’m asked how many people I killed. I say that’s between me and them.”

Peterson always refused to go back to Hong Kong and Japan in the years after the war, but he finally relented in 2011 to accept an apology offered by the Japanese government for the way the Hong Kong vets were treated.

“We were three Hong Kong veterans and they took us into a room… and the minister of foreign affairs of Japan gave us a scroll and apologized.

“I said I appreciate the apology and that I would like to forgive and forget but I can’t. But I appreciate the apology. We waited 66 years to receive an apology.”

What Peterson wants people to remember after he is gone is the ultimate futility of war.

“It’s what the War Amps say — ‘never again,’” he says.

“A war is never settled completely. There are never winners. Everyone is a loser. And the losing ones are between 19 and 30. They were the biggest losers.”

● ● ●

The historians

Polish Rabbi Michael Schudrich isn’t old enough to have been alive during the Holocaust.

But New York-born Schudrich, the Chief Rabbi of Poland, knows what happens if survivors and witnesses don’t share their experiences. Victims become lost; they are forgotten.

Before the Second World War, there were about 3.5 million Jewish people living in Poland. Three million were killed during the war, and today, according to the American Jewish Year Book, there are about 8,000 Jews in Poland.

Schudrich says while Auschwitz “is the largest Jewish cemetery in the world,” there are myriad unmarked areas where groups of Jewish people were killed during the war. And there are people still around who saw the slaughter and can remember where it happened.

But time is running out.

Late last year, Schudrich told an audience at Winnipeg’s Etz Chayim Synagogue that Polish Jews are making an effort to mark the mass gravesites of Jewish people whenever they are told where they are.

“People playing either saw the murders or found (bodies) while playing in the woods,” he says.

“We’ll talk to the old people in a village. They are happy to talk because we are unburdening them… they’re still around so we’re not stopping.

“We’ll never get to all of them, we’ll never get to some of them, but let us get as many as we can.”

More information is available at www.jcpfund.org.

Jeremy Maron, the lead researcher-curator for the Holocaust and Breaking the Silence galleries at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, says the passage of time and disappearance of living memories is what their galleries are trying to capture.

“One of the main aspects of our collection is peoples’ stories,” he says. “How they illustrate their human-rights experience. Whether the witnesses are first-hand people or second-hand survivors, that documenting helps keep it alive and documents it.

“Institutions like ours have to afford opportunities for these voices to come forward in order not just to document the injustice, but to also document them and make sure they are around for the long term.”

It’s why the museum not only documents the Ukrainian Holodomor and the Holocaust, but also allows visitors to become informed about other atrocities, including 20th-century barbarism in Rwanda and Bosnia.

“The present is already past,” he says.

● ● ●

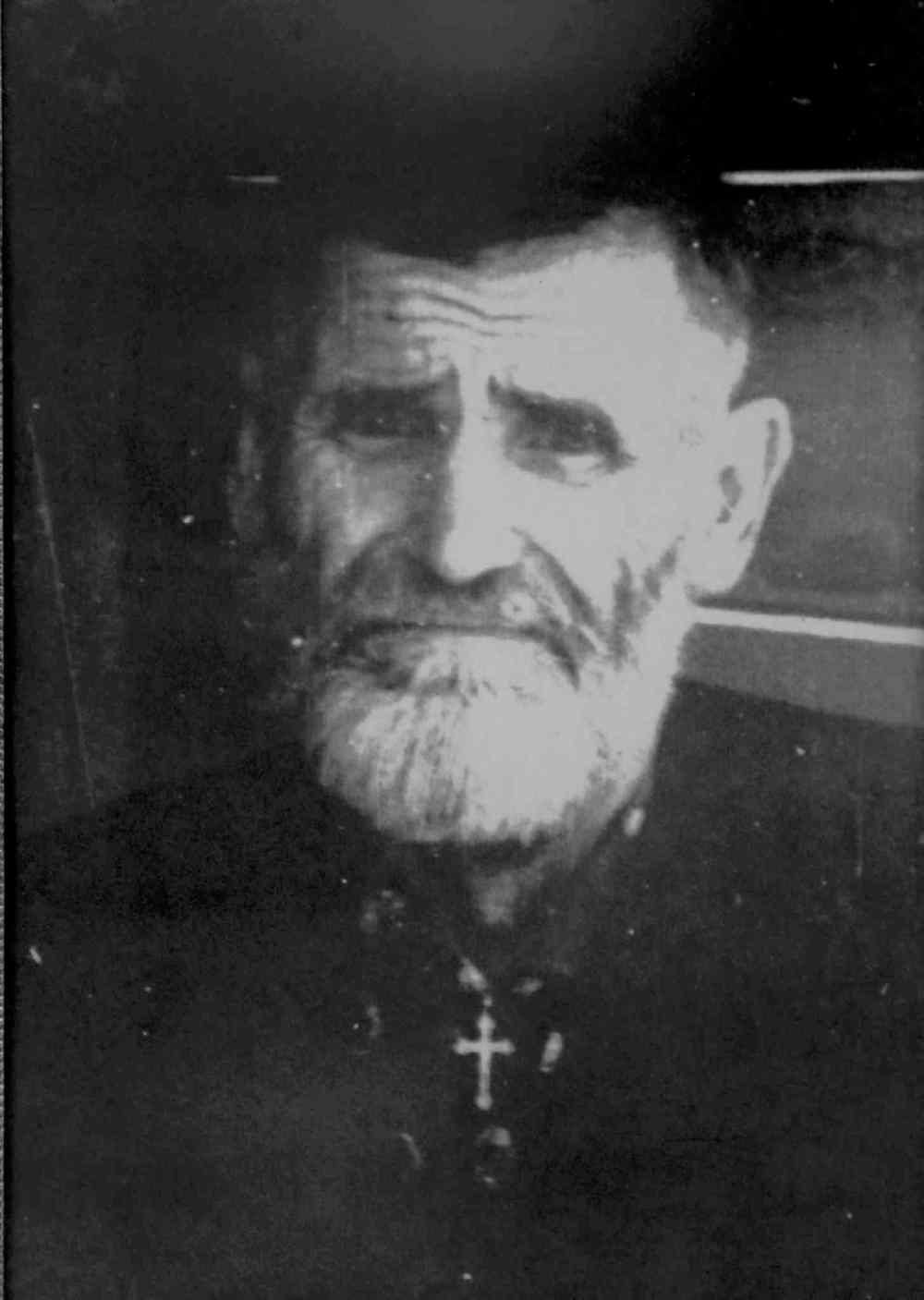

The Holodomor

Sonia Kushliak was eight years old when the Holodomor began. She’s now 93.

Her father was Andrij Sulyma, her mother’s name was Palachka and, with her two brothers and two sisters, she lived in the village of Andrushi, about 95 kilometres south of Kyiv as fall’s chill was turning to winter’s cold in late 1932.

“We had a house with a wall around it,” she says. “Everyone had a large garden and we had an orchard. Everybody had enough for their daily sustenance. And I remember the Soviets sending special teams which enlisted local communists for assistance. One of them was our very own neighbour. We were afraid of him.”

Kushliak says the teams went from house to house, gathering every bit of food they could find from kitchens and storage rooms and carting it away.

“In our food storage room we had wheat, barley, oats, other cereal crops, beans, peas and dried fruits. They took all of the stored food, even though we begged and pleaded with them to leave us even some small amount.”

And Kushliak says the teams even checked around outside in the recently frozen ground.

“They walked all around our walled yard and, with long metal poles, searched for any soft spots, looking for any buried grain and food.”

Kushliak says the neighbour even walked up to her little brother, Sasha, to try to get him to say where the family was hiding food.

“‘I will give you some chocolate,’” she says the neighbour told her brother, who didn’t respond.

“They came in and they took everything they could. We knew they were going around the village. We expected them. You could not hide anything.

“But we had some hidden in the ground — they didn’t find it.”

Kushliak said later, after the incident when she ate the bread, her father was jailed again when he was accused of letting the village collective farm fall apart due to the famine.

At the jail none of the prisoners were fed and somehow her father managed to get a note out to her mother saying “I’m starving to death.”

She says her mother went to her eight brothers and sisters who gave her the bit of food they could spare and she took it to him.

After her father was transferred to the main prison in Kyiv, her mother, when she visited him once a week, would buy loaves of bread and take them home, some for the family to eat, others to sell for a profit.

“For this, my mother was sent to jail,” Kushliak says. Her mother begged for leniency, knowing her internment would mean death for the grandparents and her five children. It worked, but instead of jail she was sentenced to spend long days whitewashing the walls of the school and buildings of the collective without pay.

Kushliak says she remembers her grandmother telling the children to spend their days lying around to reduce their hunger.

“She wanted us to stay in the yard. She told us not to run and play, to conserve our energy.”

Even so, “Our bodies started to swell, especially our legs. I remember how heavy they were. It was difficult to walk.”

Kushliak says she and her siblings hunted for food constantly. They brushed away snow in the spring looking for any fallen apples from the previous autumn that had eluded the food teams. They also gathered the empty husks from grain and mixed them with bark from birch trees to be pounded into powder to make something resembling cookies.

“It was something to put in our stomachs,” she says. “We had no feelings. It was just desperation. Eventually everyone just became emotionless. Something terrible would happen and you wouldn’t react. Not even when somebody died.”“We had no feelings. It was just desperation. Eventually everyone just became emotionless. Something terrible would happen and you wouldn’t react. Not even when somebody died.”–Sonia Kushliak

Not even when her grandfather died.

“He came in and was lying on the warming ledge of our wood-burning stove. He died silently amongst us… without a gasp. Without complaint of pain. Because of starvation.”

Kushliak says her mother’s brothers dug a grave to bury him, but when they all went to the cemetery for the funeral they were met with a horse-drawn wagon carrying the bodies of 12 women and children. She says because people were too weak to dig graves they would wait until one was prepared for someone else and ask if their loved ones could be buried in it as well. Permission granted, the bodies were deposited — a bit of dirt sprinkled on each — before her grandfather was placed on top.

When winter ended, and things began growing again, the starvation ended, she says.

“When the crops began to grow, that’s when we felt good. It was still a long road to recovery, but at least there was hope. It was a very long time before we could even speak about what happened. You never knew who would hear what you said and report it.”

Kushliak realizes her family was one of the lucky ones. Her grandfather died, but the rest of her family, including her grandmother, all lived through it.

She later went to Germany before coming to Canada in 1949, where she worked in Selkirk as a nurse at the hospital. While in Germany she had met the man who would later become her husband. She has two children and four grandchildren.

But Kushliak is the last of her generation in her family, so unlike what she did when she was younger, she says future generations have to continue speaking up to help people remember the Holodomor. She goes to ceremonies where participants hold three stalks of wheat, to remember how Stalin imposed a law making it illegal to possess more than that.

“When you’re not allowed to talk about it for years you don’t talk about it,” she says. “I get emotional when I talk about it now. I am very angry about what happened. And you get more angry as the years go by.”

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason

Reporter

Kevin Rollason is one of the more versatile reporters at the Winnipeg Free Press. Whether it is covering city hall, the law courts, or general reporting, Rollason can be counted on to not only answer the 5 Ws — Who, What, When, Where and Why — but to do it in an interesting and accessible way for readers.