‘There is space for everyone around that table’ Report shows little diversity among Winnipeg school trustees

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/07/2020 (1382 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When Greg McFarlane was running for school trustee, he contemplated putting his smiling face on his campaign signs.

On one hand, the Winnipeg father, electrician and labour advocate weighed the pros of having a white-passing name; without a photo, his race would be inconspicuous. On the other hand, he thought about his ward’s diverse population.

“If somebody sees a Black face, are they going to vote for me? Even though I’m fully qualified and have the credentials, will that help me or will that hinder me?” said McFarlane, recalling his thought process in 2014, and again, in 2018 as he prepared for his re-election campaign in the Seven Oaks School Division. “The fact I have to think about that is the problem.”

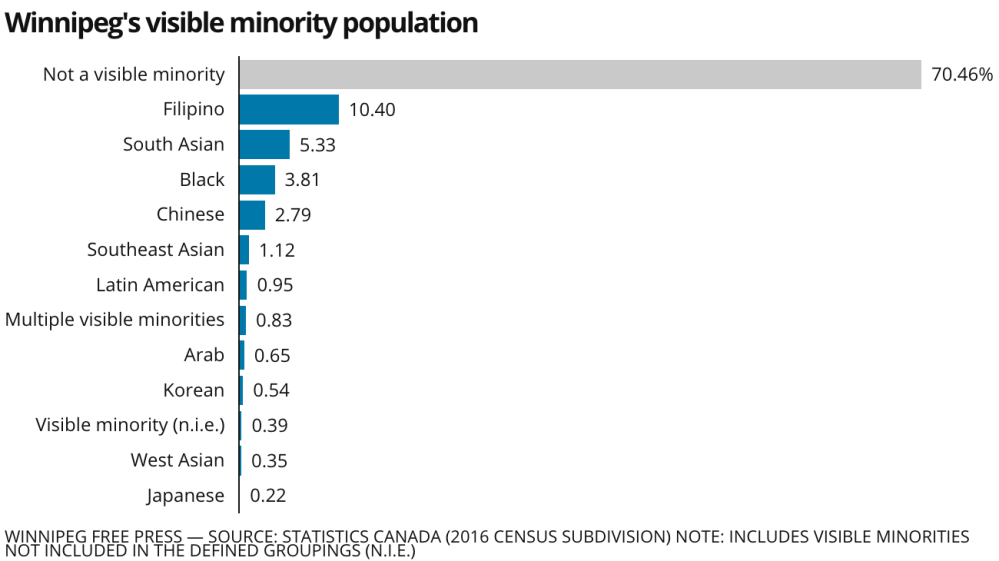

In Winnipeg, 27 per cent of the population self-identifies as a visible minority, the largest percentage of which is Filipino, followed by the South Asian, Chinese and Black communities. Twelve per cent of the population is First Nations, Métis or Inuit, or has mixed Indigenous ancestry. In the Maples, a significant section of McFarlane’s ward, the former percentage is more than double the city’s total while the latter is one per cent shy of it.

Yet, a scan of elected school trustees and senior officials who sit around education decision-making tables don’t reflect those figures. McFarlane, who grew up in the school board on which he now serves as vice-chairman, is one of a handful of racialized trustees in the Manitoba capital — and in the province at large.

This fall, the Community Education Development Association, in partnership with the Winnipeg Indigenous Executive Circle’s education committee and Newcomer Education Coalition, is expected to publish its long-awaited State of Equity in Education Report. The report, originally scheduled to be published shortly after the now-indefinitely postponed education review, will put a mirror up to divisions to compare how they reflect local families.

Among the statistics, a racial breakdown of the 2018 trustee election results: there were two self-identified Indigenous trustees and three trustees from racialized communities, of the 54 trustees on Winnipeg’s six English boards (Seven Oaks, Winnipeg, Louis Riel, Pembina Trails, St. James-Assiniboia and River East Transcona). That translates into six per cent of the trustee population identifying as racialized and less than four per cent as Indigenous.

“Ideally, in any system, not just school systems, they’re representative of our population, from the lowest level of employee to the higher level of leadership,” said Heather McCormick, chairwoman on the education committee for the Winnipeg Indigenous Executive Circle.

The lived experience of policy-makers, and employees ranging from teachers to guidance counsellors, is key to ensure learner needs are met and that all students have role models and allies, McCormick said. She added that unconscious bias plays into how board policies and educators treat students, especially those with academic and behavioural challenges.

“If somebody sees a Black face, are they going to vote for me? Even though I’m fully qualified and have the credentials, will that help me or will that hinder me? The fact I have to think about that is the problem.”

– Greg McFarlane on his campaign for Seven Oaks School Division trustee

Kathleen Vyrauen, chairwoman of the Newcomer Education Coalition, echoed those sentiments, adding that a representative board can increase parent involvement and community engagement, which better serves students. In the context of pandemic learning disruptions, Vyrauen said it has been critical for divisions to provide both translation and one-on-one support so students don’t fall behind, and to connect with ethnocultural organizations to pinpoint newcomer needs.

“Ideally, in any system, not just school systems, they’re representative of our population, from the lowest level of employee to the higher level of leadership.”

– Heather McCormick, chairwoman on the education committee for the Winnipeg Indigenous Executive Circle

WSD trustee Jamie Dumont knows first-hand how important it is to have trusting relationships with communities in order to spark policy discussion and change. “You end up with a stronger governance system when you have all those different populations represented,” Dumont said, adding she wanted to become a trustee to show her Métis children and community that, “there is a space for everyone around that table.”

Dumont said her most proud moment as a trustee was a product of her close ties with French immersion parents, who brought concerns about the limited advanced high school programming options for their children to her. The division is now reviewing how it can better support immersion students throughout their academic careers.

“It’s about time we started to have that dialogue about racism and about diversity and about having full inclusion and having Black faces in places of decision-making.”

– Greg McFarlane

Meantime, McCormick isn’t convinced Manitoba’s board structures — which were examined by the K-12 education commission — are working for everyone. “All of the systems that we work within are based on colonization,” she said. “We have these systems that were created for a certain group of people and what we’ve been doing is making everyone else fit into them versus making actual change so that everyone has equal opportunity.”

Her suggestion is revamping boards to reserve seats for representatives from different communities, similar to what was done in Nova Scotia in 2018 when that province dismantled school boards in favour of a 15-person advisory council. There are seats reserved for representatives of the Mi’kmaq First Nations, African Nova Scotian and Franco-Acadian Communities on the provincially appointed education committee in that province.

A former trustee and current African-Nova Scotian council member, Archy Beals said it’s too early to have an opinion on which system works best. However, he noted much resistance to the initial transition among the African Nova Scotian and Mi’kmaq communities. “Those two groups have been traditionally underrepresented at the table — we get to the table, and now it’s gone,” Beals said.

Back at the Seven Oaks table, McFarlane continues to share his lived experience as a Black trustee. Last month, he issued a statement to call on residents to renew their commitment “to a world free of racism.”

“It’s about time we started to have that dialogue about racism and about diversity and about having full inclusion,” he said, “and having Black faces in places of decision-making.”

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Maggie Macintosh

Reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Winnipeg Free Press. Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.