Complacency the enemy of the truth, my truth

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/06/2020 (1424 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Over the weekend I remarked to a friend that I have no idea, in this moment, how to be both black and a journalist at the same time.

As I bear witness to the protests and conflicts rippling across both the United States and Canada in opposition to police brutality and systemic anti-black racism — issues that affect my community, my people, my selfhood — I find myself faced with questions about how I will show up in my work.

How will I choose to bring light to this movement? Whose voices will I turn to? Whose stories will I amplify? Which words will I use? How will I honour myself, my people and my journalistic integrity at the same time?

It is our job, as news media, to be the witness-bearers. It is our responsibility to shine light where there is darkness and ensure systems of power are held to account. Ask nearly any journalist and they will tell you as much.

They will also tell you contrary, perhaps, to popular belief, that this is not an objective practice. This is not a neutral cause. Each of us brings our biases, our blind spots and our passions into the work we do. We make choices at every step: who we will speak to, how we will frame their voices, which stories will we write and which we will ignore. None of this is neutral.

Because none of this is neutral, journalism has the power to be complacent and complicit when our communities are faced with injustices. Journalism has the power to turn a blind eye to what is essential about these movements and focus public attention elsewhere: on property damage, on police who kneel or hug protesters (before donning masks and firing gas, that is), on voices that detract from the movements.

In situations like this, we as news media are called to make choices.

First, we must choose which voices we amplify.

There is a tendency, especially in the crushing pace of daily reporting, to lean heavily on what the police tell us has happened. We believe we are giving room to everyone’s perspective when we do this, we believe it is in the interest of balance and we fall short of critiquing and questioning what the police have said.

When 16-year-old Eishia Hudson was shot and killed by Winnipeg police in April — one of three Indigenous people killed by police in the city over a 10-day span — we called it a “police-involved shooting,” neutralizing the violence of her death.

We repeated information handed out at press briefings about the events leading up to her death before speaking with her family, with witnesses or with the Indigenous community to check facts and contextualize her death in a history of prejudice and racialized police violence.

I wrote this paper’s first article that day. That was on me.

If we are to write about these movements in the honest pursuit of truth, we must choose to centre the voices that are most affected — in the case of this week’s news I mean black voices — and we must choose to frame actions in their full context. We cannot rely on police-driven narratives. We cannot be complicit in continuing to diminish black voices by amplifying the voices that oppress them.

We must also make choices about the language we use. In journalism school I was taught to use the active voice as much as possible, but I find when we report on police brutality and racial injustice, we tend to lean away from this practice.

Protests do not erupt into violence spontaneously. Tear gas, flash bangs and rubber bullets do not deploy on crowds of their own accord.

We cannot shy away from specificity in describing the actions at play. We cannot shy away from directly acknowledging who initiates violence, fires tear gas, fires rubber bullets, fires guns, kills. We also cannot shy away from acknowledging, directly and unflinchingly, who is harmed.

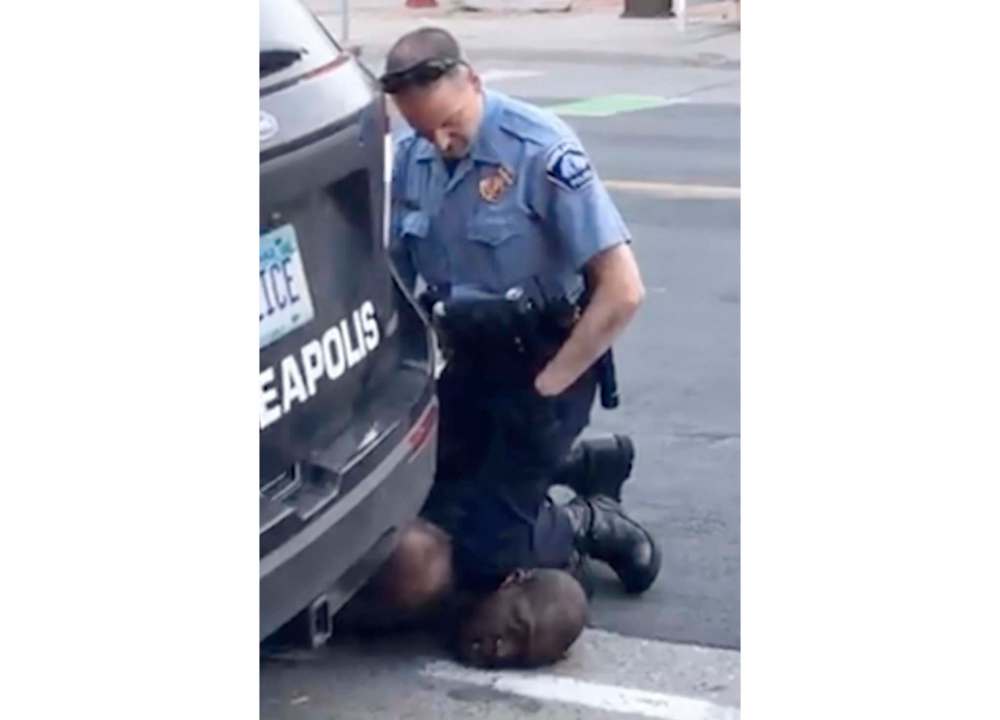

These protests are about speaking against anti-black racism and police brutality, and it is black people across Canada and the United States who are receiving the lion’s share of the violence. These protests are in solidarity with those grieving the deaths of Regis Korchinski-Paquet, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and all those who have died at the hands of police violence. This is the context and we are complicit when we refuse to acknowledge and centre it in our reporting.

In the context of protests combating police brutality, who does it serve to focus our energies on stories about cops expressing menial acts of kindness? Or about property damage to big-box stores? It certainly does not serve those who have died in police hands, or those who respond with grief and rage to their deaths.

We must choose, finally, to listen. At its core, this is our job. When we are told what the goals of a protest or action are, we must listen. When we are told what matters to the communities we report on, we must listen. When we are told we have misrepresented the voices we seek to amplify, we need to take a step back.

At the end of the day, our jobs rely on trust. Black communities, by and large, do not trust the news. In order to restore that trust it is our responsibility to critically examine our reporting and its role in perpetuating the cycles of violence that we seek to expose; to listen to, amplify and hire black voices in a news landscape that is so painfully void of our stories and our storytellers; and to heed critique when it is given.

When we neglect to centre these questions in our work, we are choosing complacence.

julia-simone.rutgers@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @jsrutgers

Julia-Simone Rutgers

Reporter

Julia-Simone Rutgers is a climate reporter with a focus on environmental issues in Manitoba. Her position is part of a three-year partnership between the Winnipeg Free Press and The Narwhal, funded by the Winnipeg Foundation.