The Riel deal Unwilling to submit to Ottawa's control over land that would become Manitoba 150 years ago, resolute Métis took up arms against and stood firm against Canada's presumptuous PM

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/12/2019 (1596 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

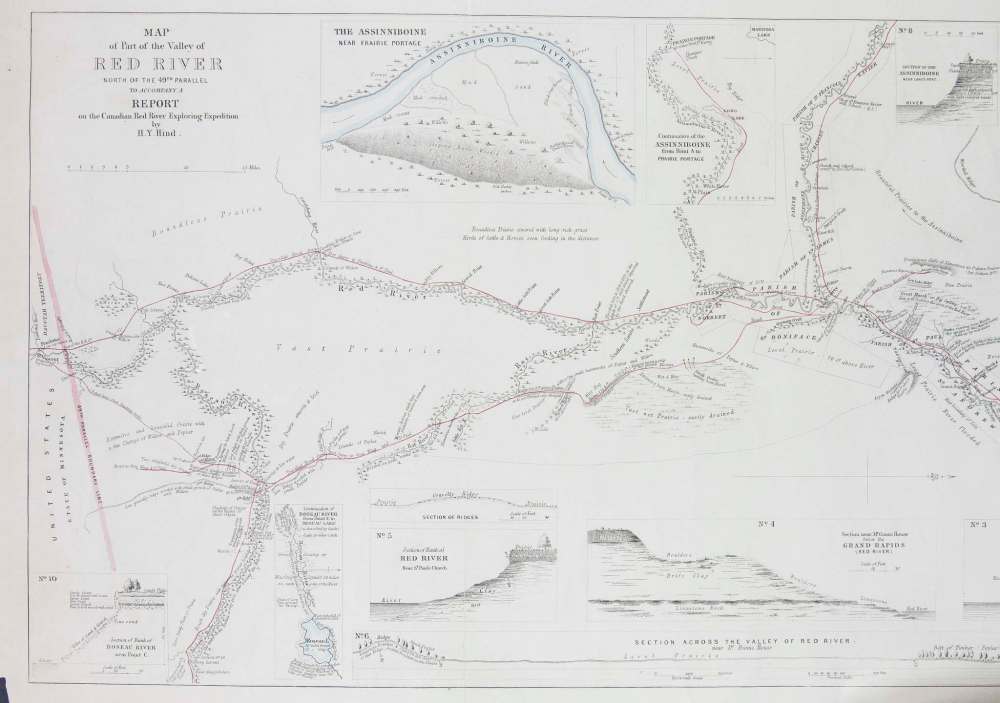

As Manitoba gets set to mark its 150th anniversary in 2020, the Free Press turns back the clock and takes an in-depth look at the dramatic story of how a small community living on the banks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers stood up to the federal government and demanded a say in the terms of joining Canada. The Red River Resistance of 1869-70 is a story of courage and determination by a group of Manitoba Métis who challenged a colonial mindset in Ottawa and took up arms to protect their democratic, cultural and legal rights.

It begins in October 1869 and culminates in the passage of the Manitoba Act by Parliament in May 1870 – a constitutional amendment that still serves today as the legal framework for Manitoba’s place in Canada. The following is the first instalment of a three-part series that will follow the timeline of what unfolded in the Red River Settlement 150 years ago, and the events that led to Manitoba’s entry into Confederation.

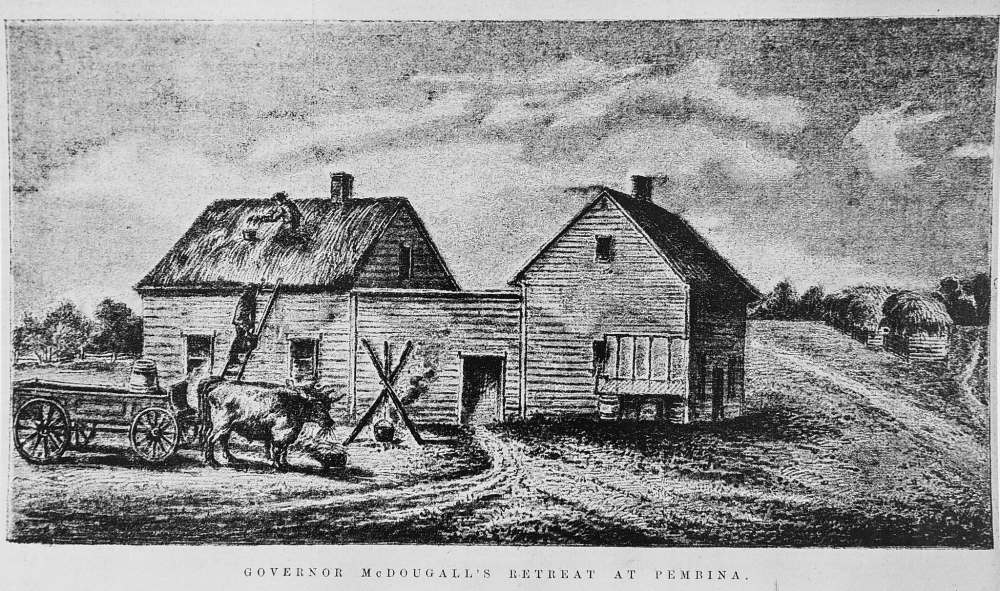

WILLIAM McDougall had one of the finest homes in the Red River Settlement picked out for him in the parish of St. James, about 10 kilometres west of Upper Fort Garry. It was said to be the most suitable dwelling in the territory for a lieutenant-governor.

McDougall was on his way by ox cart to Red River in the fall of 1869, his family and a large contingent of staff and federal officials in tow. He was chosen by Canada’s then-prime minister John A. Macdonald to be the first lieutenant-governor of Rupert’s Land and the Northwest Territories. The Ontario-born politician saw himself as a natural candidate for the job. He was a former federal cabinet minister and a Father of Confederation who long advocated the Canadian annexation of the Northwest. Earlier that year, he helped negotiate Canada’s purchase of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company. He quipped to Macdonald, when the prime minister saw him off at the train station in Ottawa a few weeks earlier, that the appointment was like being dubbed “king” of the Northwest.

The main players

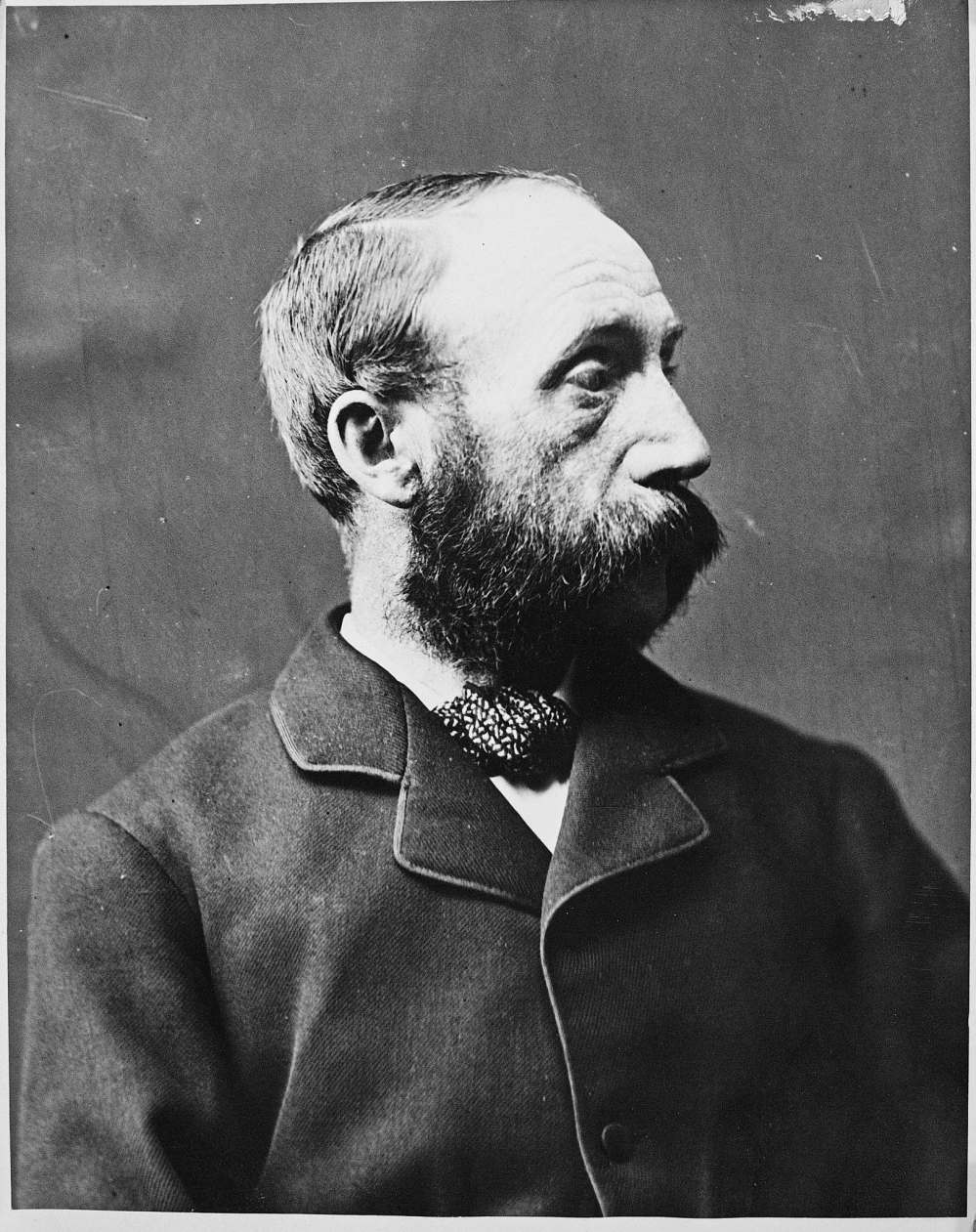

William McDougall: The former federal cabinet minister was appointed lieutenant-governor of Rupert’s Land, but never took his place as the Queen’s representative in Red River. After the Métis refused him entry into the territory, McDougall eventually returned to Ottawa.

Louis Riel: The leader of the French Métis and central figure in the Red River Resistance. Riel was instrumental in finding unity among francophones and anglophones in efforts to negotiate the terms of entry into Confederation with the federal government.

William McDougall: The former federal cabinet minister was appointed lieutenant-governor of Rupert’s Land, but never took his place as the Queen’s representative in Red River. After the Métis refused him entry into the territory, McDougall eventually returned to Ottawa.

Louis Riel: The leader of the French Métis and central figure in the Red River Resistance. Riel was instrumental in finding unity among francophones and anglophones in efforts to negotiate the terms of entry into Confederation with the federal government.

James Ross: The leader of the anglophone Métis. Ross often butted heads with Riel and questioned the Métis leader’s militant approach. But ultimately both leaders found common ground in the creation of a provisional government.

John A. Macdonald: Canada’s prime minister at the time of the Red River Resistance. Following the armed uprising, Macdonald was forced to negotiate with the Métis on the terms of Manitoba’s entry into Canada.

John Christian Schultz: A self-described Canadian “loyalist,” Schultz was Riel’s chief nemesis in Red River. Schultz was imprisoned by Métis leaders at Upper Fort Garry along with other supporters, after opposing the Métis resistance against Canada.

William Mactavish: Hudson’s Bay Company governor at the time of the resistance, stationed at Upper Fort Garry. Mactavish was powerless to stop the Métis when they seized the fort and set up their command base there.

McDougall would never see the inside of the St. James home, nor would he assume his position as the Queen’s representative in the Red River Settlement. The lieutenant-governor designate was refused entry into the territory. He and his entourage were stopped just past the U.S. border by a party of French Métis, who objected to the federal government’s attempt to unilaterally take over their land. It was a brazen stance that escalated into a seven-month, David-and-Goliath showdown between the people of Red River and the Dominion of Canada. It was the first chapter in the compelling story of how Manitoba became Canada’s fifth province.

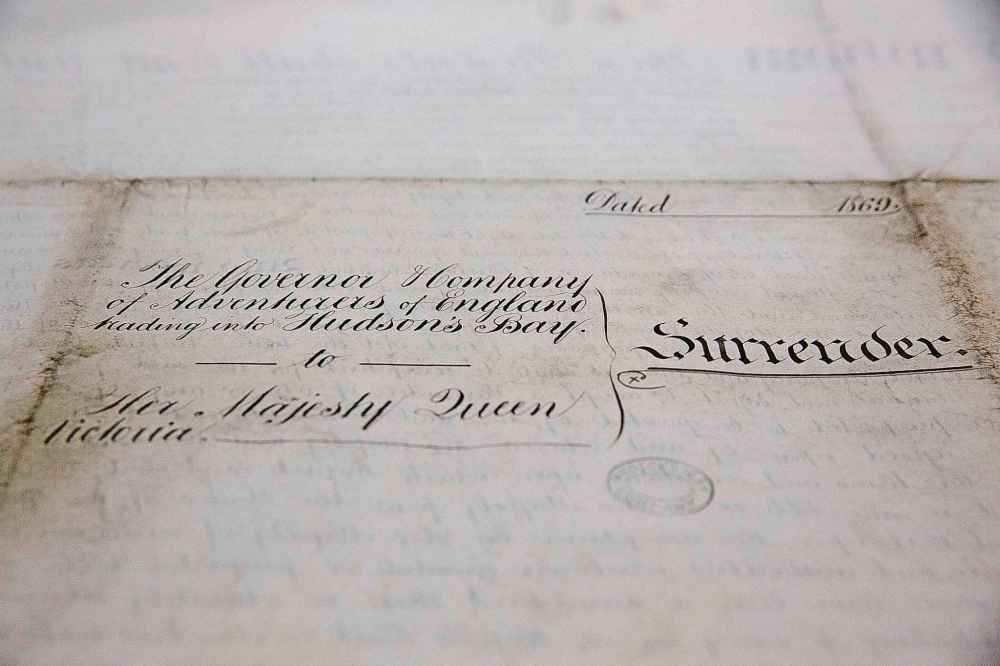

When Rupert’s Land was purchased by the Canadian government from HBC in the spring of 1869, it came as a surprise to the estimated 12,000 people living in Red River (what is now Winnipeg and the surrounding area). They were neither consulted about the land transfer, nor asked for their input into joining Confederation. One of the most significant transfers of land and sovereignty in history was about to occur, yet the federal government was treating it “as a mere transaction in real estate,” Manitoba historian William L. Morton noted in his 1957 book Manitoba: A History.

The Rupert’s Land purchase was Canada’s first step in opening the West to imperial rule. It was scheduled to take effect Dec. 1 – 150 years ago this month. McDougall and his entourage had been travelling north to Red River in a large caravan from St. Cloud, Minn., where the railroad ended in those days. Travelling through the U.S. by rail was the only way to get to Red River from the east in 1869.

By the 1860s, HBC rule of the Northwest was winding down. A more democratic governance structure and the opening of new trade corridors were seen as important developments in improving the standard of living in the region. Most people in Red River, including Métis leader Louis Riel, were not opposed to joining Canada, which had formed 2 1/2 years earlier. Many considered themselves British subjects and were loyal to the Queen, regardless of their French, English, Catholic, Protestant or Indigenous backgrounds. The people of Red River — made up largely of French and English-speaking Métis — even celebrated Queen Victoria’s birthday every year.

But they weren’t willing to join Confederation unconditionally. Unlike the historic meetings that took place in Charlottetown, P.E.I., and Quebec City a few years earlier to hammer out the details of the new federation, no Canadian delegates were sent to Red River in 1869 to negotiate the terms of entry. It wasn’t even contemplated. When McDougall showed up at their doorstep in late October, the people of Red River had no commitment from the federal government that their language, culture, religion or land holdings would be protected.

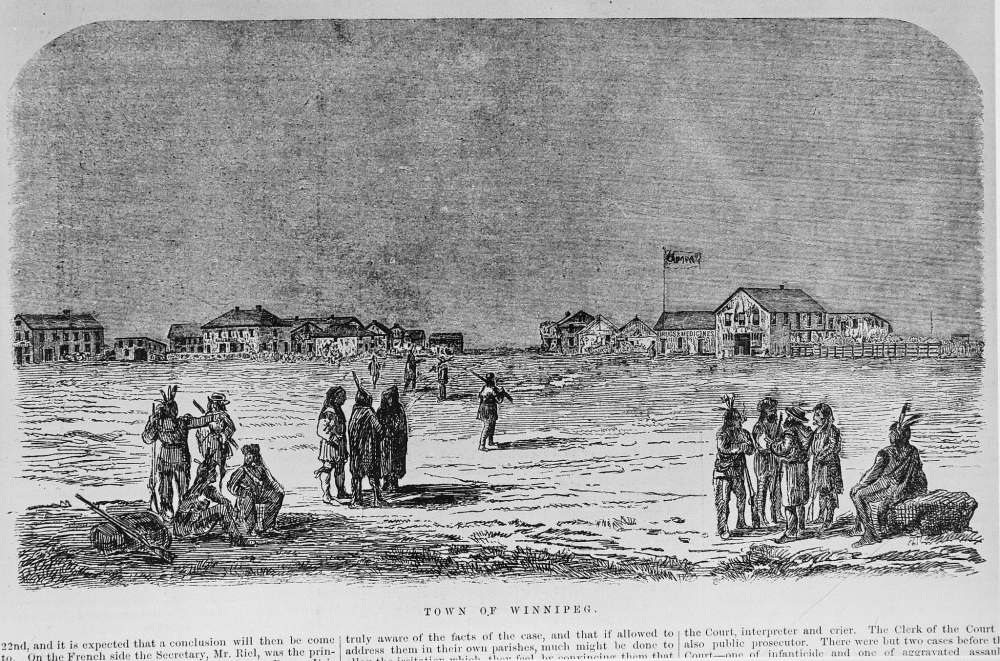

Red River, including the village of Winnipeg, was an isolated community in 1869. But it was no backwater. The region had a court system; a “General Quarterly Court” that met four times a year to hear criminal and civil cases, and a “petty court” for small claims. There were churches, a library, mail service, bars, hotels and farmland. A robust ox-cart trade corridor to the U.S. was developing as the buffalo hunt wound down. An American consul was appointed to Red River that summer.

The District of Assiniboia, as it was also called, was rich in culture and language. It was also a relatively free community. Settlers were governed by the HBC, but not with an iron fist. A municipal-style “Council of Assiniboia” administered local matters. Order was maintained largely through the consent of the people. There were racial and religious tensions (as there are today). But the Métis — both French and English — the Scottish settlers, First Nations and the smattering of Americans and Canadians who made up the community, worked, worshipped, celebrated and traded in relative harmony. When Canada came knocking, they were afraid of losing that way of life.

The federal government’s plan was to govern the region as a territory at first, with provincial status coming later. It would be run by a lieutenant-governor and a federally appointed council. Without provincial status and a democratically elected legislative assembly, there were no assurances settlers would have a say in local affairs. Worse, Red River would soon be overrun by Ontario settlers, who would snap up land and risk disrupting the social equilibrium that had developed over generations.

Canada was warned repeatedly about its flawed plan to barge in and take over without consultation, including from William Mactavish, the HBC’s territorial governor, who travelled to Ottawa several months earlier. He strongly urged the federal government to discuss the terms of Confederation with the community prior to annexation. His advice fell on deaf ears.

Alexander Begg, a Red River merchant at the time who chronicled much of the events around the resistance, put it this way in a Nov. 10, 1869 letter to the Toronto Globe newspaper: “It is quite apparent to intelligent people here, as it will be generally admitted in Canada when all the facts are known, that the government at Ottawa have made a serious mistake in the outset of their assuming the rule over the North-West.”

The story of the Red River Resistance is complex. The political narrative and the events that drove the resistance (and ultimately the creation of Manitoba) were shaped by religious and racial conflict, local infighting and a colonial mindset in Ottawa. To this day there remains a heated debate about whether the armed uprising was a justified response to an overbearing imperialist force or an act of disloyalty to Canada. As Manitoba historian J.M. Bumsted wrote in Louis Riel V. Canada, the historical record of the resistance “can be interpreted in almost any way one chooses.”

Regardless of that interpretation, what happened in 1869-70 Red River — warts, glory and all — is the story of how Manitoba entered Confederation 150 years ago.

● ● ●

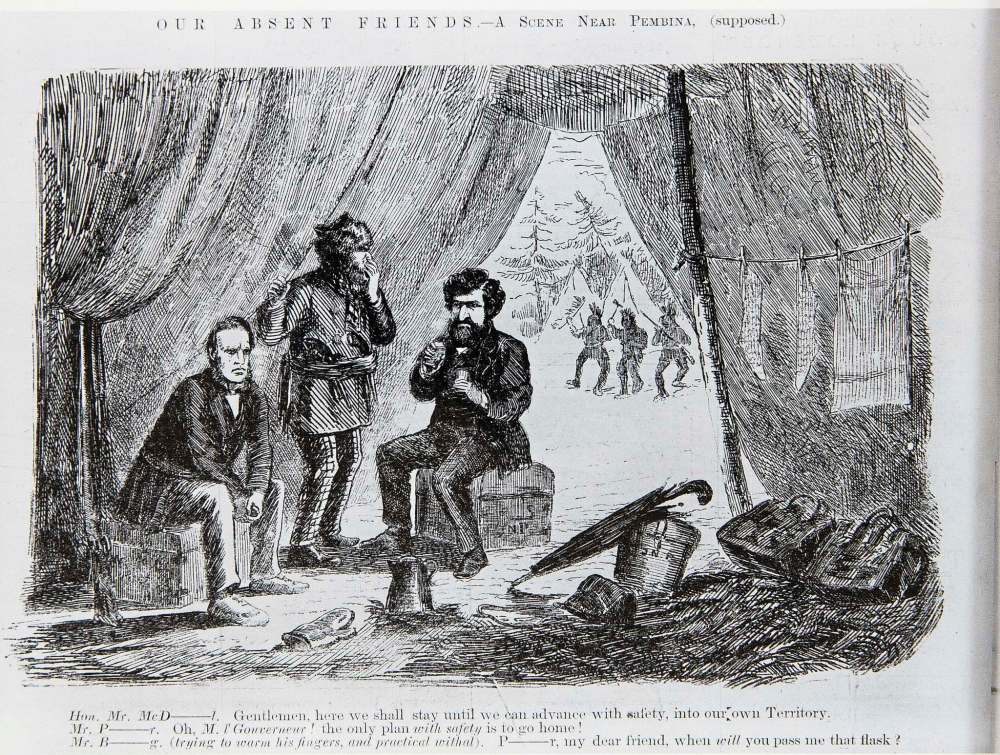

When McDougall and his entourage arrived at Pembina, just south of the U.S. border, on Oct. 30, 1869, they were shocked to find two Métis representatives waiting for them with a communique. The short note ordered an indignant McDougall not to enter the North-West, by order of “the government.” It wasn’t the first act of resistance by the Métis against Ottawa. Throughout the summer, local residents prevented federal representatives — who were sent to Rupert’s Land long before the scheduled land transfer — from surveying their land. In early October, Louis Riel and others famously stood on a surveyor’s chain in an act of defiance that set the stage for the coming standoff.

McDougall ignored the order not to cross the border. The lieutenant-governor designate and his entourage moved further north. But they didn’t get far. They reached a small Hudson’s Bay trading post just a few kilometres past Pembina. This time, McDougall was ordered by a party of armed Métis to return south of the border and warned not to cross the line again.

Trying to repel a unilateral takeover by Canada was no easy task. Riel and the Métis knew they had to secure the territory as best they could. They erected a barricade at St. Norbert and deployed armed, mounted guards to police the trail between Red River and the U.S. border. Anyone coming into the territory was checked for credentials and queried about the nature of their business. It was the closest thing to martial law the small community could muster.

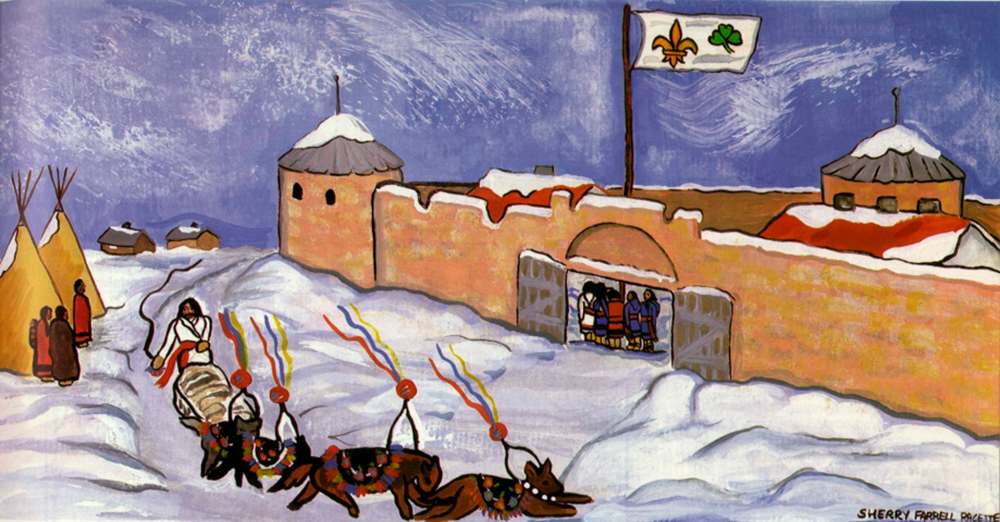

The same day McDougall was forced back to Pembina — Nov. 2 — a party of Métis seized Upper Fort Garry (the original stone gates of which still stand at the corner of Broadway and Main Street in downtown Winnipeg). Upper Fort Garry was the HBC headquarters for the territory. It housed company offices, stores and quarters for staff and the governor. Despite the importance of the fort as a central post, seizing it was remarkably easy and bloodless. A group of armed Métis simply walked in and took over. There was virtually no resistance from HBC officials (and little they could do, since there was no local military and barely any policing in 1869 Red River).

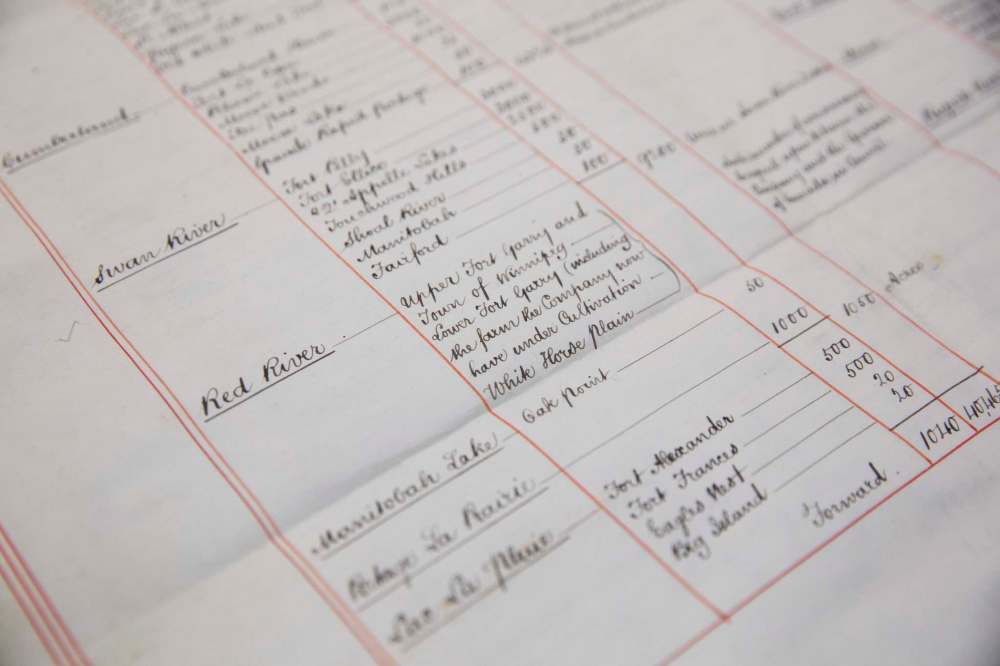

The Métis needed a base that would eventually serve as headquarters for its provisional government. But they also had to remain a step ahead of a small group of Canadian “loyalists” living in Red River, led by John Christian Schultz, who opposed the resistance and abhorred the idea of French, Catholic Métis interfering in the annexation process. Having command of the fort — which contained months of food supplies, firearms, financial and other records (including land title documents), as well as cash — was a key element in maintaining control of the area. It served not only as a command post but a jail the Métis would soon use to incarcerate those who challenged their authority (mainly Schultz and his “Canadian Party” supporters).

By then a “national committee” of francophone Métis had been established. Riel was elected secretary and John Bruce, a St. Norbert carpenter who would never have a prominent role in the resistance, was president. Riel had relatively good solidarity among the French Métis by the fall of 1869. But English-speaking Métis and other settlers were still skeptical of his methods. Many saw the armed uprising, and keeping the lieutenant-governor designate in exile, as rash. Convincing them to join the fold would be critical.

Louis Riel was only 25 years old at the time, but highly educated and bilingual after studying for the priesthood in Montreal as a teen and a young man (he never became a priest). Like his father Louis Riel Sr. — who decades earlier fought for Métis trading rights in Red River — Riel had natural leadership skills and a keen sense of the political environment around him. He knew that even though the French-speaking Métis outnumbered the English, presenting a united front was key to establishing the legitimacy required to negotiate the terms of entry into Confederation.

Days after taking the fort, Riel published a notice inviting one representative from each of the 10 English-speaking parishes in the area, and two from Winnipeg, to attend what would be an important series of meetings at Upper Fort Garry in November. The anglophones responded, sending delegates from each parish. It was a small, but important victory for the francophone Métis.

The meetings were heated, but constructive. James Ross, a one-time part-owner of the local Nor’ Wester newspaper, was the leader of the anglophone Métis. Like Riel, Ross was relatively young at age 26 and also educated in Eastern Canada. The two often sparred over Riel’s militant approach, including the decision to block McDougall from entering the territory.

Keeping McDougall at bay was strategically important for several reasons. If the lieutenant-governor designate were allowed in, even under the guise of negotiating the terms of entry into Confederation, the Métis would lose the leverage they had. McDougall had no authority to negotiate on behalf of the federal government. He sent a representative to Red River while holed up in Pembina to try to begin talks, but to no avail. Riel would accept nothing less than face-to-face negotiations with authorized federal representatives. Blocking McDougall from entering would also be a key factor in establishing legitimacy in a soon-to-be declared provisional government.

.jpg?w=1000)

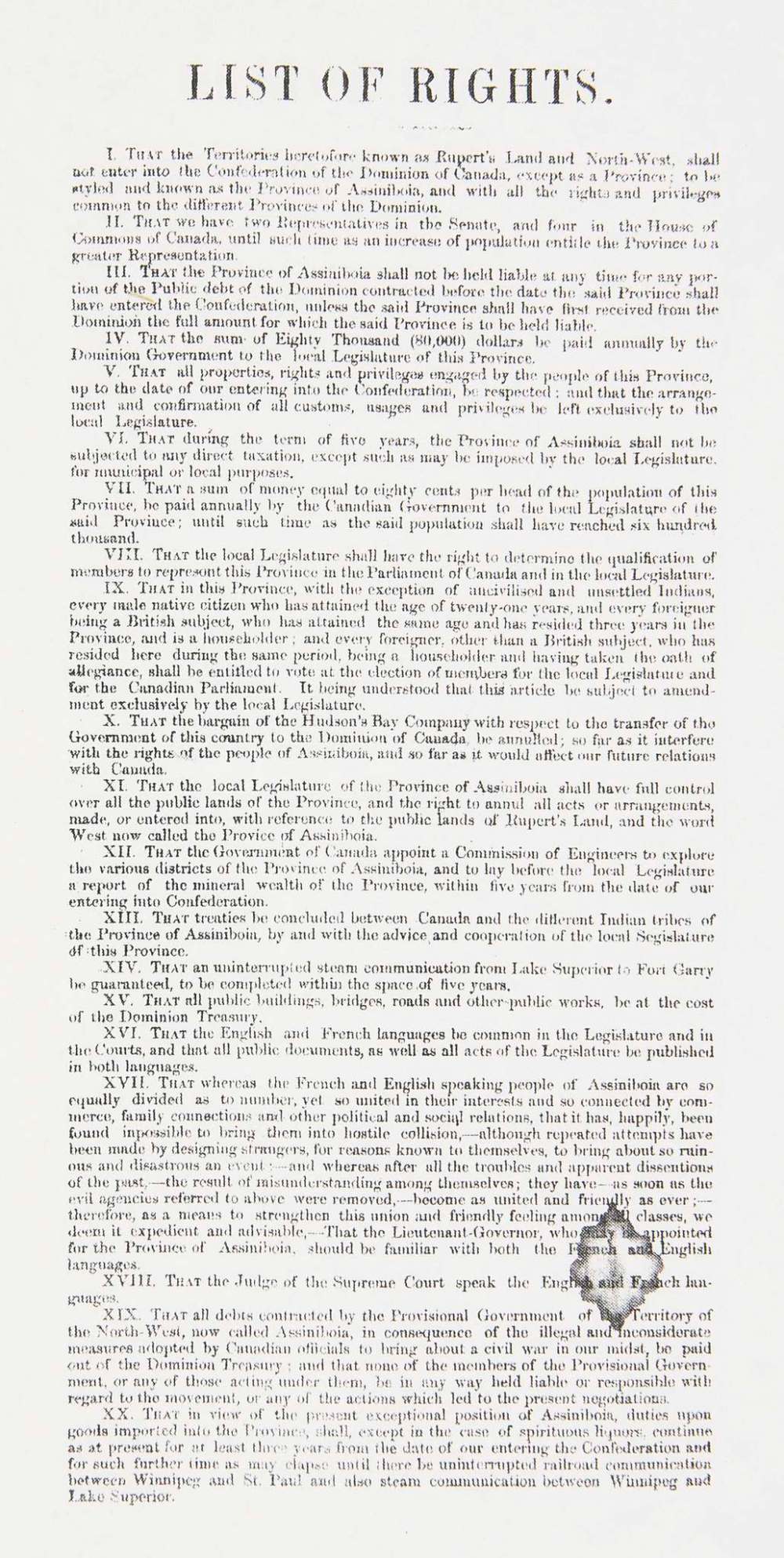

The November meetings between the French and English Métis were fruitful. They led to an agreed-upon “list of rights” by delegates, a set of conditions to join Confederation that included the protection of language, religious and democratic rights. The list would evolve over the next few months. But it formed the basis of what a delegation would eventually take to Ottawa in early 1870.

Creating a provisional government was a trickier affair. But it was important in establishing the legitimacy required to negotiate with Ottawa. The Hudson’s Bay Company had title to the land until Dec. 1. Overriding that authority before then would have been seen as an illegal takeover. But once HBC’s title expired, local residents were within their rights to establish their own government. As long as McDougall was stuck in Pembina and unable to exercise authority, a void would be created that a provisional government could fill.

Riel and the Métis were keenly aware of this “law of nations” principle. So was the prime minister, who by then received word of the resistance and McDougall’s troubles at the border. In what became a game of political chess between Riel and Macdonald, the prime minister cabled Britain on Nov. 26 and cancelled the Dec. 1 transfer. As long as the HBC still ruled, Macdonald knew a provisional government wouldn’t have legitimacy.

But because Ottawa had no immediate communication with McDougall, the lieutenant-governor designate wasn’t aware of the cancellation. He was previously instructed not to declare Canadian authority in Red River until he got the green light from Ottawa. However, an impatient McDougall issued a proclamation anyway on Dec. 1. He crossed the border in the dead of night in frigid temperatures at midnight on Nov. 30 and read the proclamation to a dark, empty plain.

McDougall had the proclamation printed up surreptitiously by a small group of Canadian supporters in Red River through a makeshift printing press. By doing so, he effectively extinguished HBC rule, even though his proclamation was illegal, which neither he nor Riel knew at the time. As Bumsted put it: “By Macdonald’s own calculation, McDougall’s actions had made the establishment of a provisional government legitimate.”

Riel and the francophone Métis were already working on the early stages of a provisional government by then. But once McDougall’s proclamation came, which included instructions to establish an armed militia, provoking further resistance, a provisional government was announced within days. On Dec. 8, a “Declaration of the People of Rupert’s Land” was issued. Two days later, a provisional government flag was hoisted at Upper Fort Garry and the Métis celebrated with gunfire salutes, drink and music from the St. Boniface Boys’ Brass Band.

John A. Macdonald had been outmanoeuvred.

The francophone Métis still didn’t have the support of their anglophone counterparts in the provisional government. But it was the first step in getting them on board. Riel and the Métis still had many hurdles to overcome. The new year would bring more unrest, new challenges and a controversial decision by Riel and the provisional government that would forever change the complexion of the resistance. In the meantime, the people of Red River were now in a much better position to negotiate the terms of entry into Confederation.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Red River Resistance chronology

1869

• March: Canadian government negotiates terms of purchasing Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company for 300,000 pounds.

• June 4: Prime minister John A. Macdonald introduces a bill in Parliament outlining the temporary governance model for Rupert’s Land, including the appointment of a lieutenant-governor. The lieutenant-governor would govern with advice from an appointed council.

• August: Surveyors show up in Red River, sent by the federal government, well before the official transfer of HBC land to Canada, scheduled for Dec. 1.

• Oct. 11: A group of 18 Métis, including Louis Riel, halt surveyors on the land of Andre Nault (a few kilometres from The Forks) by standing on the survey chain.

• Oct. 19: The French Métis elect a “national committee” to begin organizing against the federal government’s plan to unilaterally impose its sovereignty on the Red River Settlement. Louis Riel is elected secretary and John Bruce president.

• Oct. 30: Lieutenant-governor designate William McDougall — appointed by the federal government to head the new administration in Rupert’s Land — arrives at Pembina with a large entourage from Ottawa. He is handed a communique by two Métis representatives instructing him not to enter the territory.

• Nov. 2: McDougall is escorted by armed Métis back over the U.S. border and told not to return. On the same day, Riel and the Métis seize Upper Fort Garry.

• Nov. 6: Riel and the French Métis issue an invitation to the English-speaking parishes in Red River to send representatives to meet at Fort Garry.

• Nov. 16: The first in a series of meetings between 12 francophone and 12 anglophone Métis representatives take place at the courthouse at Upper Fort Garry. A “list of rights” is agreed on as the first draft of conditions to enter Confederation.

• Nov. 23: Riel seizes financial and administrative records, including land title documents, from HBC office in Upper Fort Garry.

• Nov. 24: Métis establish a provisional government.

• Nov. 26: Canadian government cables Britain and requests delay in Dec. 1 land transfer date.

• Dec. 1: McDougall issues illegal proclamation that land transfer from HBC to Canada is in effect. Sends instructions to set up an armed militia in Red River to police the area during the transition (a militia is never established).

• Dec. 7: Hundreds of armed Métis surround the home of Canadian “loyalist” John Christian Schultz in the village of Winnipeg on suspicion dozens of “Canadian Party” supporters inside were plotting an armed uprising against the Métis. More than 40 surrender peacefully, including Schultz, and are taken prisoner at Upper Fort Garry.

• Dec. 8: Riel and the French Métis publicly announce creation of a provisional government by issuing a “Declaration of the People of Rupert’s Land” on grounds that HBC abandoned them and transferred land to a “strange power.”

• Dec. 10: Provisional government flag hoisted at Upper Fort Garry. Métis celebrate.

• Mid-December: McDougall leaves Pembina and returns to Ottawa. Federal government sends two emissaries to Red River to confer with Métis. They bring with them a proclamation from then-governor general John Young, guaranteeing “rights” for the Métis if they abandon their uprising. Métis turn down offer in the absence of face-to-face negotiations with authorized federal representatives.

• Dec. 27: Canadian government sends another emissary, this time Donald A. Smith, who is authorized to invite a delegation of at least two to Ottawa to discuss terms of entry into Confederation. For the first time, federal government shows willingness to negotiate, although Smith is viewed with suspicion by the Métis.

Tom Brodbeck

Columnist

Tom has been covering Manitoba politics since the early 1990s and joined the Winnipeg Free Press news team in 2019.

![Thomas Scott (c. 1842 – 1870) was an Irish-born Canadian and fervent Orangeman. Scott was born in the Clandeboye area of County Down, in what is now Northern Ireland.[1] He was recruited by Canada to fight in the Red River Rebellion and was captured and imprisoned in Upper Fort Garry by Louis Riel and his men while trying to attack it along with 34 other volunteers. Scott made an attempt to escape but was recaptured by Riel's men and was summarily executed for committing insubordination. Scott's execution led to an outrage in Ontario, and was largely responsible for prompting the Wolseley Expedition, which forced Louis Riel, now branded a murderer, to flee the settlement. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Scott_%28Orangeman%29](https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/05/Thomas+Scott.jpg?w=100)