Our sentry for a century Manitoba's shining symbol of progress survived a First World War bombing and a perilous trip from Europe before taking its place on Broadway

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/11/2019 (1624 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Once upon a little over a century ago, it appears Manitoba’s most recognizable man was almost made a woman.

“La figure pourrait représenter le succès ou le progrès de Manitoba ou n’importe quoi,” British architect Frank Worthington Simon wrote to French sculptor Georges Gardet in August 1915.

The sculpture could represent Manitoba’s success or progress or anything.

“Ce n’est pas nécessaire non plus que ce soit une femme,” Simon said.

It doesn’t have to be a woman, either.

More than four years later, on Nov. 21, 1919, Gardet’s bronzed handiwork would be hoisted atop the legislature’s dome.

The third and current Manitoba legislative building didn’t officially open until 1920, but the Golden Boy — officially named “Eternal Youth and the Spirit of Enterprise” — took his perch early, keeping watch on the northwest.

Vital statistics

Height: 5.25 metres (17.2 feet)

Weight: 1,650 kilograms (3,640 pounds)

Distance from ground: 76.2 metres from the tip of his torch (255 feet)

Body measurements:

Chest: 2.4 metres (96 inches)

Neck: 88.9 centimetres (35 inches)

Right arm: 1.3 metres (52 inches)

Waist: 1.9 metres (76 inches)

Thigh: 1.3 metres (52 inches)

Calf: 96.5 centimetres (38 inches)

Weighing in at 1,650 kilograms and standing 5.25 metres tall, his significance was compared to Manitoba’s version of the Statue of Liberty in New York City, although he was modelled after Giovanni da Bologna’s statue of Mercury.

The Golden Boy was also likened to Hermes. Early sketches from Gardet also showed wings sprouting from the statue’s head and feet, like Hermes, but they were later removed.

“Like Hermes, the messenger of the gods in Greek mythology, the boy is a runner, for this western province is not content to stand still,” a 1988 government release stated. “He faces the north, with its wealth of minerals, fish, lumber, furs and water power, and its sub-arctic seaport.”

When he was boosted up in 1919, carrying a sheaf of wheat (to represent commerce) and a torch (to represent enterprise), the Golden Boy’s assignment was ambitious.

“Here you have no mountains to which you can lift up your hearts. And so you have all the more need of great architecture to lift them up,” Simon said around the time of the Legislative Building’s opening.

“Men and women cannot be happy or good in surroundings that are commonplace, ugly (or) uninspiring.”

Simon suggested the new building would “make people around it more perceptive, more intelligent, better balanced and altogether more civilized human beings.”

While no one can definitively say whether that wish came true, one can wonder how gazing at a nude man atop the legislature for 100 years has affected Manitobans’ psyche.

“If the figure on the summit of Manitoba’s Legislative Building had been a woman, one can safely assume that it would not have been a naked runner holding a torch aloft with one arm and carrying a sheaf of wheat with the other,” wrote Hubert G. Mayes in a 1993 Beaver article, a precursor to Canadian History magazine.

The Golden Boy has been the vanguard of a very male space, where elected women have always been the minority and a female premier has yet to govern. He has also been considered a gay icon by many in the LGBTTQ+ community, towering over what was once Winnipeg’s busiest cruising neighbourhood.

● ● ●

Had Simon and Gardet known they were crafting one of Manitoba’s most beloved symbols, they didn’t let on during their years of letter correspondence, some of which is available at the Archives of Manitoba.

Gardet, a sculptor well known for creating large, lifelike animal statues, was excited to be asked to create sculptures for the new Manitoba parliament. In a 1913 letter, he told Simon he would be “très heureux de collaborer à la décoration de votre beau Palais” (i.e. very happy to collaborate on decorating the new legislative palace.)

The men wrote back and forth for years, almost entirely in French. They ironed out details of how, among other challenges, the Golden Boy would stand atop the dome without falling over. They speculated about where to buy bronze and steel rods during wartime shortages and pondered when the First World War might indeed be over.

In July 1916, Gardet responded to questions from Simon about how difficult it would be to transport their giant statue overseas. While the dimensions and cold wouldn’t normally prove too challenging, Gardet said, with the war on, there might be complications.

“En souhaitant que l’année 1917 nous apporte une paix victorieuse qui vous permettra de terminer tranquillement vos travaux,” Gardet wrote to Simon in December 1916.

Here’s hoping 1917 brings us a peaceful victory that helps you finish your work quietly.

The Golden Boy was lucky to even make it out in one piece from the factory where he was built. The Barbidienne Foundry near Paris was bombed in 1918 by the Germans and, miraculously, the statue was the only item inside that survived, according to news reports of the era.

He was then tucked in the bowels of a ship that transported troops and materials across the Atlantic Ocean, zig-zagging on at least five trips between continents before finally being docked in New York City in 1919.

Shipped by rail to Winnipeg, he arrived in August 1919 and waited in the Legislative Building’s shadows.

It would be a few more months before the Golden Boy was lifted to his drafty pedestal on Nov. 21, 1919.

● ● ●

Local sculptor Jordan Van Sewell isn’t sure why a reporter would be calling to ask him about the Golden Boy on a recent Tuesday, but hazards a guess.

Is it because of recent news stories about famous figurines getting the boot? The fate of statues in public places of John A. Macdonald, the country’s first prime minister, who was integral to the creation of the residential school system, have been debated across Canada and, in at least one case in Victoria, removed.

Was the Golden Boy’s time almost up?

No, it’s the statue’s 100th anniversary atop the dome. The Golden Boy hasn’t caused that much controversy. Not yet, anyway.

Van Sewell was relieved.

“I’m always of the mind: don’t mess with tradition, right?” he said. “I think that as a traditionalist and as an advocate of the significance of our history, I think it’s really important to have that Golden Boy in place. But I do like the idea of introducing guest players or something to go up there.”

For example, the artist points to several of the maquettes in his studio space at The Forks he thinks could be enlarged for the big stage. A version of Chadwick the Bear, for example, would be a great fit to represent the North, he said.

In the early 2000s, when the Golden Boy was temporarily taken down for a good bath and rebuffing, Van Sewell created a significantly smaller stand-in of sorts. “Business is Good” depicted an aluminum boy pointing north, riding on the shoulders of a suit-clad businessman.

The aluminum version was sold to a Toronto businessman a while ago, he said, adding he doesn’t remember the purchase price, but it “wasn’t as much as the Golden Boy.”

He guessed the sculpture, which stood about 60 centimetres tall and weighed close to 4.5 kilogram changed hands for around $4,000.

“He wanted to take it out of circulation. Perhaps he was a traditionalist as well,” Van Sewell said, laughing. “It’s like talking about Wexit… if you introduce the topic, then people are going to talk about it.”

While Van Sewell has drawn inspiration from the Golden Boy for other pieces, including posters and pottery, he’s not the only local artist to have done so.

Indie rockers The Weakerthans’ sang of “our golden business boy, (who) will watch the North End die” in their 2003 hit, One Great City!

In an email this week, John K. Samson, who wrote the song, explained why he referenced the Golden Boy.

“I was taught in elementary school that the Golden Boy faces north because that’s where Manitoba’s resources lie, but not about the racist colonialism of resource extraction,” he said.

“In the song (One Great City!), the Golden Boy, standing in for capitalism, watches impassively as he causes poverty and injustice, and then claims he is doing it for the larger good.” – John K. Samson

“In the song, the Golden Boy, standing in for capitalism, watches impassively as he causes poverty and injustice, and then claims he is doing it for the larger good.”

Samson said he regretted the line might be misinterpreted as implying the North End has somehow been defeated, when that’s not the case.

“I believe the North End is and has always been full of real community and amazing resistance to colonial capitalism and represents the best hope for a just and sustainable Winnipeg and world,” he said.

Performance artists Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Millan raised eyebrows when they added sexual politics to their homegrown tourism campaign called One Gay City! in 1997.

Their poster campaign featured three portraits, each with its own slogan. Perhaps the most striking of the trio featured a gilded, pouting Golden Boy facsimile, alongside the slogan: “Where everyone is light in the loafers… Winnipeg: One Gay City!”

The posters were meant to run in city bus shelters, but the ad agency responsible for their placements refused to run them. Dempsey and Millan fought the censorship at the Manitoba Human Rights Commission and ultimately settled with the ad agency in 1999.

In a recent interview, Dempsey said the aim of the campaign was to shame then-mayor Susan Thompson into acknowledging Pride festivities and recognizing queer communities in Winnipeg. When Glen Murray was elected as the first openly gay mayor in North America in 1998, the artists felt they didn’t need to press on further.

Dempsey and Millan also gave out Golden Boy awards in the ‘90s to “unscrupulous” politicians. (Had they continued that tradition into 2019, the need would be so great, they’d be “working 24/7,” Dempsey joked.)

Dempsey, who also teaches women and gender studies at the University of Winnipeg, considers the Golden Boy as a gay icon.

“He’s such a queer-looking, beautiful young man. He really could be in gay porn,” she said with a laugh.

“He’s really sort of a certain type of idealized, young male beauty. And of course the Greeks were very comfortable with homosexuality, as we know, and he being a representation of a Greek god, it all fits nicely.”

The grounds behind the Golden Boy — the south lawn near the Assiniboine River — are also well known.

Valerie Korinek, a University of Saskatchewan history professor, noted the spot was a famous cruising location for gay men between from about the 1930s to the 1970s.

in her 2018 book, Prairie Fairies: A History of Queer Communities and People in Western Canada, she details how the Golden Boy was a “literal signpost” for the gay community.

“So Winnipeg is unique because it has Golden Boy, but all of the cities (in the Prairies) have similar locations for cruising: by rivers, in parks, near landmark buildings, whether they were railway hotels or, in this case, the legislature,” Korinek said in an interview.

While she’s made research trips to Winnipeg, the professor said she hasn’t seen the Golden Boy up close yet. She watched news reports with some awe in Saskatoon as the statue came down in 2002, and noticed how Manitobans took a deep interest in its restoration.

“People seemed to care very deeply about that statue. They’re proud of him,” she said.

“And I think that’s sort of very Prairie in the way that people are very proud of their home cities and communities. There’s this tremendous boosterism to always claim we’re the biggest, the best, the whatever. So he’s an image that’s embraced by Winnipeggers.”

● ● ●

If you do want to get up close and personal with the Golden Boy, be prepared to climb about 319 stairs and 18 ladder rungs.

Vanessa Gregg, who manages building tours for the legislative assembly, has made the trek up and down the winding staircases many times in her 15-year tenure.

Visitors are always eager to hear about the man at the top, she said, whether they’re schoolchildren or adults.

And while the public doesn’t normally get this up close and personal with Golden Boy — popping out of a portal under his toes at one point to get a good view of his bare armpit and face — they still remain enamoured.

“There’s just something about him. Because he’s so large, because he’s the only one in all of Canada, because he’s a symbol for us here in Manitoba — the symbol of our future and prosperity. He’s just very well loved,” Gregg said during a recent, chilly interview atop the legislature’s roof.

For her, the Golden Boy is also a symbol of an outsider being brought into the fray; someone welcomed with open arms. He was from France, after all, and made an arduous journey to get here.

“So a lot of people living in Manitoba, we have a lot of people who’ve lived here forever, for centuries and many generations back. But we also have people who haven’t been here for that long,” she said.

“And so he, having been here for 100 years, is kind of established in that sense. But there’s a lot of people who aren’t.”

There’s a couple of myths about the Golden Boy Gregg would also like to dispel.

One is that he was a gift from France, as the Statue of Liberty was to the United States. Alas, he was indeed paid for, and Gardet had the receipts to prove it.

The second common misconception is that he was lost at sea.

“He was never lost… It’s more that we didn’t have GPS tracking like we do now to know where the boat was,” Gregg said.

“His trip here wasn’t easy, but when he arrived we were happy to see him.”

jessica.botelho@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @_jessbu

A brief history

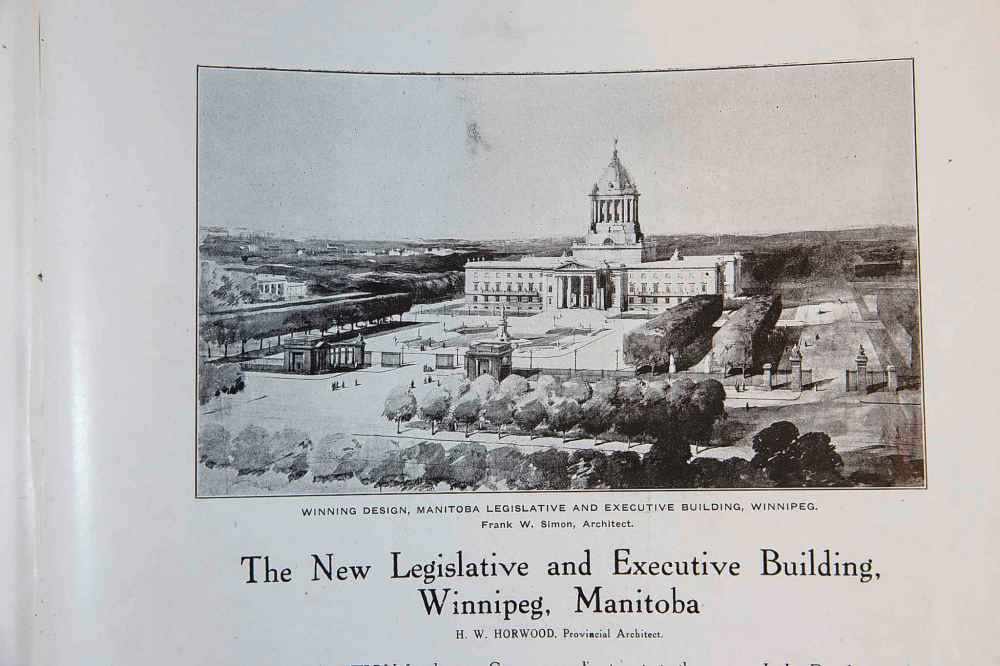

December 1911: The Manitoba government announced a competition looking for architects to design a third version of the provincial legislature to be located between Broadway and the Assiniboine River.

November 1912: According to an archived issue of Construction Magazine, the competition was considered by the architectural profession as “one of the fairest competitions ever conducted in Canada.” Of 67 submissions, two were chosen — an entry by Frank Worthington Simon and Henry Boddington III of London, England and an entry by the Maxwell Brothers of Montreal, who won similar contests in Regina and Edmonton. The Brits’ design ultimately won.

Late 1912 and 1913: Simon and Boddington got to work on plans for the Legislative Building, including contacting an old schoolmate of Simon’s from L’École Des Beaux-arts in Paris. In a letter, Simon asked Georges Gardet, a sculptor known for his large animal pieces, whether he would like to contribute some work for the new legislature. Gardet replied that he would be very happy to collaborate.

1914-17: Simon and Gardet corresponded through letters for years, many of which are available at the Archives of Manitoba. They negotiated details about the sculptures’ designs, how much materials would cost and what countries were best to procure them in. They also commiserated about how the First World War was affecting their work and their countries’ soldiers.

Though Simon insisted it wasn’t necessary, Gardet pushed him to sign a work contract so he wasn’t swindled out of money, as he mentioned a colleague had been while dealing with the Mexican government.

The pair ultimately decided on three sets of sculptures Gardet would make: two giant bison for either side of the grand staircase, two larger-than-life statues of Moses and Solon for the legislative chamber and one massive man to stand atop the dome.

July 1918: According to a Winnipeg Tribune article from the time, the Barbidienne Foundry near Paris had been bombed by the Germans. Most of the factory was destroyed — but the Golden Boy survived. Shortly afterward, he was placed in a ship bound for North America.

Late 1918-August 1919: The Golden Boy’s transatlantic trip took several months. “He was left bedded down in the ship’s hold, and from then until the war ended he braved the perils of wartime seas with men of the ship’s crew and with the thousands of allied soldiers the vessel transported,” according to a 1952 article in Western Business and Industry magazine. The statue was finally unloaded in New York City and then shipped by rail to Winnipeg.

September 1919: Though the building was not yet finished, the legislature had an unofficial opening during a visit from the Prince of Wales. The Golden Boy waited on the ground, along with other statues representing industry, art, learning and agriculture.

Nov. 21, 1919: The Golden Boy was installed on the dome, though he was initially nicknamed the Bronze Boy. He was not painted gold until later.

July 15, 1920: The Manitoba legislature officially opened, costing about $9 million, a far cry from the initial estimate of about $2 million.

1930s-’40s – After being re-bronzed in 1936, the statue’s skin succumbed to the elements, becoming a “dirty green” colour, according to news articles from the time. In 1937, a Free Press headline read: “Golden Boy’s Torch Dimmed by Dust of 20 Years; Sheaf of Wheat would Grade No Better Than No. 6, Smutty.” The statue was painted gold in the 1940s by contractors perched on scaffolding in the sky.

1951: With gold paint not a long-term solution, either, the government decided to hire workers to cover the statue in 23-karat gold leaf imported from Paris. About 50,000 square inches of the tissue-thin leaf allegedly cost about $500 at the time. Contractor Dick Baxter told local media, the Golden Boy’s new skin would be “pure as mother’s wedding ring.”

Dec. 31, 1966: To celebrate Canada’s centennial in 1967, the Golden Boy’s torch was electrified and lit on New Year’s Eve. It was supposed to be lit only for the year, but the light was popular, and became permanent until the early 2000s.

2002: Despite a few cleanings over the years from on high, the Golden Boy was lowered for a more thorough scrubbing. His torch was snuffed for good due to water and weather damage that occurred after being wired.

After a time on display at the Manitoba Museum, giving thousands an up-close look at the hardy Manitoban, the statue was repaired and then re-gilded at The Forks, this time with a 24-karat skin costing about $5,600. The entire restoration project cost about $1.1 million.

October 2002: The Golden Boy returned to his north-facing perch just in time for a visit from the Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh. As part of a pilot project, sensors were installed in the statue to allow for monitoring of weather patterns, winds and any new damage.

The government debated putting the statue’s “vital statistics” online in response to interest from members of the public, but ultimately decided against the move. A provincial spokesperson said recently the statistics are no longer being monitored.

Nov. 21, 2019: The Golden Boy celebrates 100 years atop the Legislative Building.

— Jessica Botelho-Urbanski

History

Updated on Friday, November 15, 2019 6:44 PM CST: corrects name of Solon statue