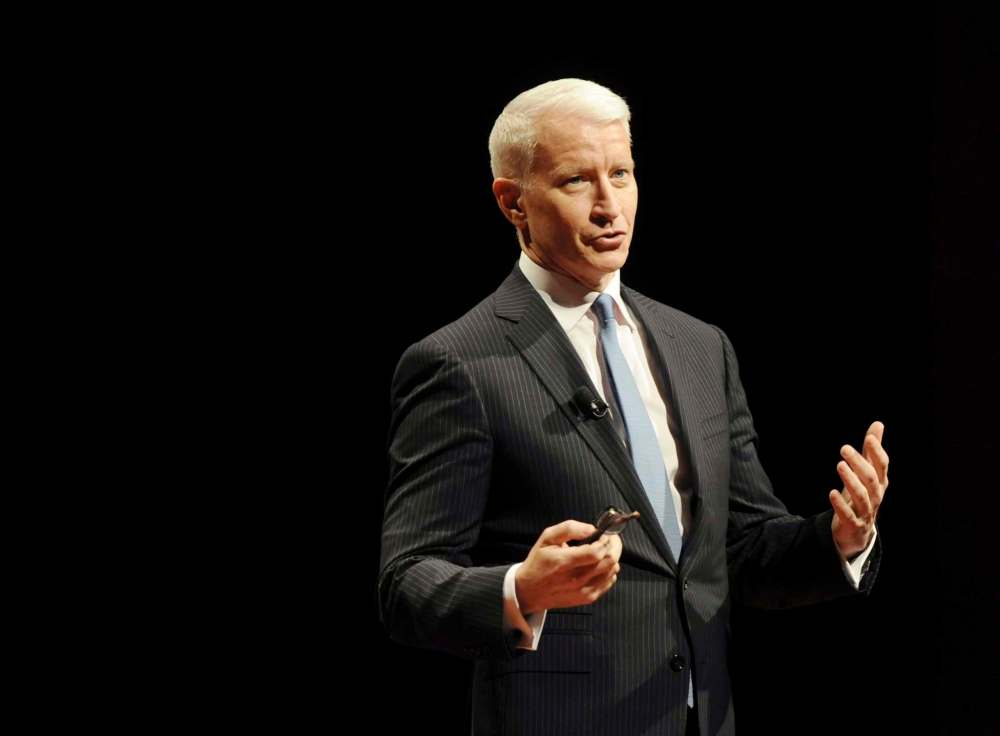

Unsinkable anchor CNN reporter has made a career of keeping people in the conversation

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/09/2019 (1688 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

For the past 16 years, American journalist Anderson Cooper has been a nightly voice of reason in living rooms all over North America as the anchor of CNN’s award-winning news program, Anderson Cooper 360°.

Event preview

An Evening With Anderson Cooper

● Sunday, Sept. 15, 7 p.m.

● Centennial Concert Hall

● Tickets $74.75-$175 at centennialconcerthall.com or at 204-949-3999

His intimate, on-the-ground reporting style has not only netted awards, it has set the bar for modern television news. And we’re in a whole new world, now, with Cooper covering (and fact-checking) a U.S. president who refers to his news organization as the “enemy of the American people.”

“Many presidents have viewed media as the enemy. They just haven’t announced it to the American people always, or they might have grumbled that to their aide in the Oval Office, or yelled to their aides about coverage,” Cooper says. “But yeah, to have the president of the United States declare reporters the enemy of the American people is obviously insulting, it’s obviously wrong and highly inappropriate, and one of many factually inaccurate statements and inappropriate statements this president has made.

“But the Obama administration stopped allowing me to interview President Obama because they were upset with coverage I did of the BP oil spill. So I’ve had administrations be mad at me before, and that’s fine.

“Our job is not be friends with these people. Whether it’s a Democratic or Republican administration, my job is to ask questions.”

In advance of his Winnipeg appearance on Sunday at the Centennial Concert Hall, the Free Press put Cooper, 52, on the other side of the microphone to talk about the evolution of the news anchor, President Trump fatigue, and his relationship with his mother, the late fashion icon Gloria Vanderbilt.

Jen Zoratti: There has been a real shift, not just in the way news is consumed, but the way it’s delivered — and I think you are part of that shift. It used to be that a news anchor was this all-knowing, authoritative voice from on high. What role does the news anchor play in 2019?

Anderson Cooper: I think that’s a really good question. There’s certainly been an evolution. I grew up watching Walter Cronkite and Dan Rather, I grew up watching the old-time CBS news correspondents; Bob Simon was an idol of mine who died just a few years ago, worked at 60 Minutes but was an incredible foreign correspondent. I never took journalism classes, but I read a lot about reporters in the Vietnam War, and books by reporters like Michael Herr’s Dispatches. That’s what got me interested in travelling to places and telling stories.

When I started to do it, I had a home video camera, a friend of mine made a press pass for me, which was basically just a made-up laminated card, and I just started going to wars. I snuck into Burma/Myanmar, I hooked up with some students fighting the government. I ended up in Somalia in the early days of famine. The style of storytelling that I started with — and frankly still continue to do — was a movement away from that traditional way of shooting stuff. That was really because of necessity. I didn’t have a crew; I would turn the camera and talk to the camera. In Somalia, I hired a couple kids with AK-47s and I would ask one of them to, like, shoulder his weapon and hold the camera for a second…

When you’re in a war zone or a famine, you can’t just stand there and talk from on high in a distant way about what you’re seeing, because what you’re seeing is overwhelming. You want to bring the viewer along on the journey you’re on, and what you’re seeing and smelling and hearing. That, to me, required a more intimate style.

Jen Zoratti: Who is telling these stories has also changed.

Anderson Cooper: Yeah, absolutely, and thank goodness. The people on the screen should reflect the people of the country — not just racially, but gender and sexual orientation and politics. All of that stuff, when you look back at what was considered the Golden Age of television, in the U.S. there like three broadcast networks and the evening news was 15 minutes long. The idea who can tell everything that needs to be known in 15 minutes and it’s all being told by white, middle-aged men — nothing against white, middle-aged men as I am a white, middle-aged man now, I guess. It’s important to have different voices at every level: in front of the camera, behind the camera, producing.

Jen Zoratti: And then, of course, there’s the pace. A 24-hour news cycle is like a 12-hour news cycle now.

Anderson Cooper: I would argue it’s like a 15-minute news cycle now. I don’t think it’s hours. It is radically different from two or three years ago. We plan a show all day long and, if five minutes before air or in the middle of our broadcast, we have to toss out everything we’ve planned because a new tweet has been sent that sends things into a whole other direction. Things are moving so fast that the outrage from today gets replaced with some new outrage.

At times, it feels like there is too much information and it’s coming at us from all directions. I think it’s more important than ever before to know where your information is coming from, to say, ‘Wait a minute, the stuff I’m reading on Twitter — is this an actual news organization with reporters and fact-checkers and levels of people with human eyeballs reading this story making sure the story is accurate, or is this a Russian bot somewhere or a person in a basement just putting stuff out and trying to manipulate the news cycle?’

Jen Zoratti: How do you deal with information fatigue?

Anderson Cooper: I can tell you I’ve stopped Twitter. I’ll read Twitter for news, but the whole comments section is inundated with bots and stuff that’s cracked out by advocacy groups. I don’t even look at it anymore. As someone who tries to be mindful and meditate and be present in my life, Twitter is the exact opposite of that. I’ve taken myself out of it, and my life is much more pleasant.

Jen Zoratti: On the flip side, it seems dangerous to tune out completely, which brings us to Donald Trump.

Anderson Cooper: Plenty of people are already had a stage where they’re tuning out and they just don’t want it in their life anymore. Donald Trump has lived this way his entire life, surrounded by chaos and drama. Dorothy Parker said, ‘Those born to the storm find the calm very boring.’ This is the atmosphere he lives in and always has.

I think it’s exhausting for people in the White House, I think the number of people who have come and gone is unprecedented, and finding good, qualified people to fill the important jobs is difficult, because people don’t want to be in the whirlwind that is every day. And you have to cover it. You have to point out what’s true and what’s not.

If people have tuned out, that’s their decision. But nothing’s ever going to come from people stepping out of the conversation, or even monitoring the conversation. That’s part of the strategy, to have things be so exhaustingly grinding you just tune out and give up. That can be a business strategy, it can be a political strategy, and it’s arguably the strategy the president knows very well.

Jen Zoratti: Changing subjects completely: You lost your mom in June, and you had that beautiful opportunity a few years ago with your book (2016’s The Rainbow Comes and Goes: A Mother and Son on Life, Love, and Loss). I’ve always been a big believer in interviewing your family, while you can, even if you’re not a professional journalist. Tell me about how this came about.

Anderson Cooper: My mom had turned 91, and on her 91st birthday, she sent me this interesting email — she was big on email in her 80s and 90s — and I’m not going to get this completely right, but it was intriguing, her perspective, on being 91 and remembering a birthday wish from her aunt when she turned 17.

One of the terrible things about losing a parent, and my dad died when I was 10, is you forget. You forget what they sound like, you forget what they look like, you forget what they smell like, and you never learn a lot of the stories of who they actually were — not as your parent, but who they were as a human being. When my mom turned 91, I thought, ‘I don’t want that to happen with my mom. I don’t want there to be anything unsaid left between us.’ And so, when she sent me that email, I just emailed her back and said, ‘I’d like to start this thing where we have a conversation over the course of the next year through email, maybe in person sometimes.’ I never thought it would be a book. We just wanted to get to know each other while there was still time.

And it was life-changing. I not only learned a lot about her, I realized how like her I was. I always thought I was like my dad. To discover how much of her is in me was fascinating. And slightly alarming, because they weren’t always the most practical attributes.

Jen Zoratti: Such as?

Anderson Cooper: We were in the hospital the day she found out she had terminal cancer and I was taping a little bit right after she found out. She was making a joke about something and she started giggling, and I started giggling. I discovered that my ridiculous giggle — which people have made fun of me for years about — is actually her giggle.

I encourage people to try to do that with a parent, or a parent with a child. You learn things about yourself you might never expect.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti

Columnist

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.