Show of force

Winnipeg police using tactical unit for minor calls, data show

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/01/2018 (2295 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

OTTAWA — Winnipeg’s heavily armed police unit regularly responds to suicide threats, traffic issues and even matters involving panhandlers, which is raising questions about how the tactical team is used.

A recent study by University of Winnipeg researchers reveals the Winnipeg Police Service barely tracks the types of calls its Tactical Support Team (TST) responds to, making it almost impossible to compare how often it is deployed for high-risk situations, versus more mundane calls for service.

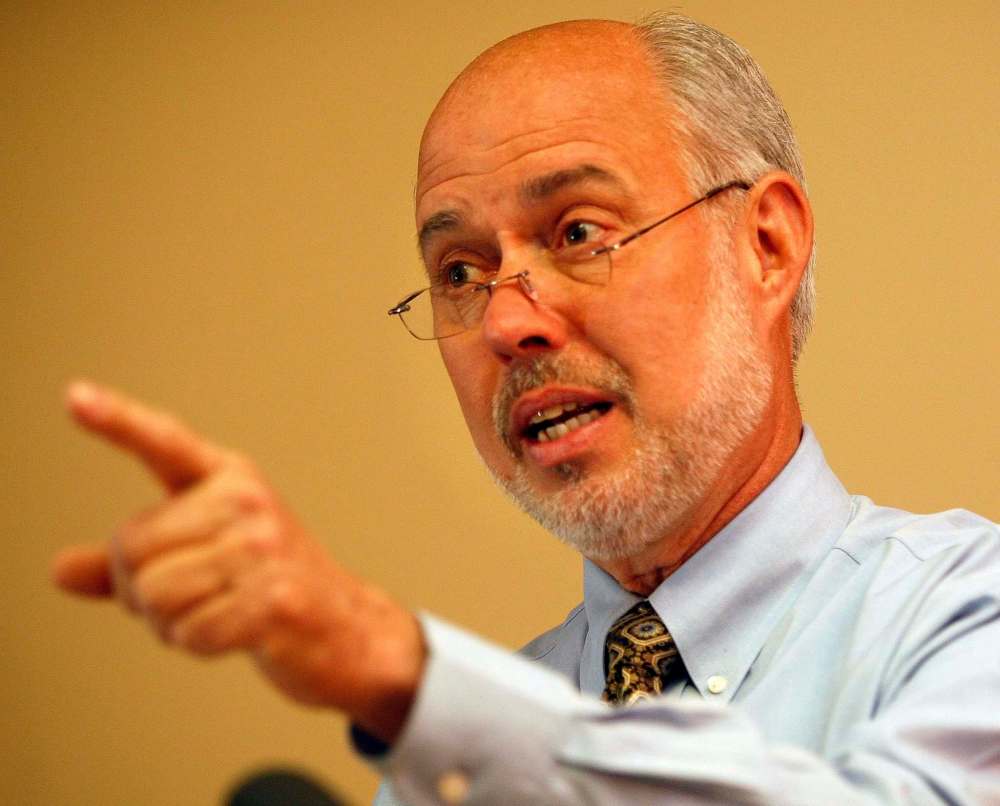

“SWAT teams are being used for all kinds of instances that are not even close to the most dangerous or the most violent,” said Kevin Walby, an associate professor of criminal justice, who co-authored a study on Canadian police forces in the journal Critical Criminology last fall.

“If these kinds of trends that we’ve found go unchecked, then there’s no real stopping the SWAT team being used for almost anything that police do.”

Walby and his honours student Brendan Roziere combed through 540 pages of documentation released through access-to-information laws and found Winnipeg’s tactical team frequently responds to mental-health issues, which experts worry could further antagonize people in distress.

“The public understands that these are units that would be called into, say, hostage situations or active shooters,” Roziere said. “But the reality is that this unit is actually deploying to quite mundane policing activities.”

However, Winnipeg police say they intentionally integrate tactical officers into regular police work, and call them as needed for high-risk situations. But it’s hard to tell how many calls fit in either category, some five years after two independent reports called out the unit for flimsy record-keeping.

For instance, TST records suggest the unit’s calls jumped almost sixfold between 2013 and 2016. But the researchers are certain that’s due to inconsistent data collection rather than a dramatic rise in calls.

Roziere said that makes it hard for Winnipeggers to scrutinize how police use their resources, including purchasing armoured vehicles.

“It’s hard to dispute what the police are saying when they’re the ones that hold all that data.”

The documents obtained indicate Winnipeg tactical officers were deployed just under 500 times in 2013, and nearly 3,400 times in 2016. Meanwhile, an operation review in 2012 said the unit responded to nearly 2,000 calls in 2012.

“It seems to me there would have to be a significant problem with their own data-collection policies, for them to be involved in as many incidents,” said Roziere, who also analyzed data from Ottawa, Calgary and Vancouver police, as well as Ontario’s provincial force.

“The Winnipeg police seem to use their units more often than the other cities that we’ve looked at.”

Winnipeg Insp. John Lutz said the tactical support unit intentionally attends a mix of calls.

“They’re police officers first, and they’re on the street a lot when they’re not training,” said Lutz, who oversees the team along with other specialized divisions.

Some 37 officers staff the unit, including a co-ordinator who can be called out to operational duties. They work in four shifts of nine members, typically covering the hours from 7 a.m. to 2:30 a.m.

“There are high-risk incidents in this city, but they’re not all the time. So when they’re not doing those, (tactical officers) are making good use of the time, and having good, productive value for the taxpayer,” said Lutz, who added officers almost always wear body armour, but can use different body language and less threatening equipment for low-risk calls.

Yet Walby said this approach is hindered by “haphazard” data collection, where it’s unclear whether the unit had classified an incident as a routine call or a high-risk threat.

“What’s the threshold? What’s the line going to be? There has to be some kind of criteria to deploy this level of force,” Walby said.

“These are life-and-death decisions to use the SWAT team or not. So I’d expect pretty rigorous document preparation and storage around these things, in case there was some kind of investigation or inquiry.”

● ● ●

Two 2013 operational reviews of the Winnipeg police recommended the tactical team track its annual workload and operation success, in order to assess its cost and staffing. WPS spokeswoman Ally Siatecki says the force has opted not to produce monthly or annual reports.

“We have the ability to run that data if we require it, but we don’t run and keep that data on a regular basis as a practice,” she wrote.

Sam Alvaro, a part-time criminology professor at the University of Ottawa, said tactical teams have been responding to non-emergency calls for decades, making it hard to assess their use.

“Until you get a good idea of what those guys are doing, it does look a bit like a dog’s breakfast,” Alvaro said.

He said cities often only confront whether tactical teams are being used appropriately when there’s an abuse of power or a controversial death.

“When it comes to the police, there always needs to be transparency. And it’s extremely unfortunate, because they’re always under the microscope, but at the end of the day they provide a vital function and they do need to be transparent with us.”

Walby said he’s concerned Canadian police forces could soon resemble American ones, where SWAT teams there have ballooned in size and in usage over the past decade.

Surveys by American researchers such as Peter Kraska have suggested a self-perpetuating logic to tactical teams, where they report to lower-risk incidents to keep busy during days with limited calls, and eventually end up spending most of their time on routine incidents.

“What we’re asking for is some kind of clear criteria or threshold, when the SWAT team is going to be used,” Walby said. “Because it seems like there’s been this kind of creep, where they’re being used in all kinds of (routine) instances.”

Roziere warned Canada could follow the U.S. if it doesn’t have an open conversation about how often the units should be deployed, especially amid falling crime rates.

“We can’t really say it’s not a possibility, that our police forces wouldn’t go down that route, we already see police more buying vehicles,” he said, referring to the $343,000 armoured rescue vehicle purchased in summer 2016.

But Alvaro cautioned against applying U.S. trends to Canada.

For one, Canadian forces aren’t buying large vehicles from the military in the same way that the U.S. army has offloaded equipment and tanks used in the Iraq war. The Winnipeg study also seems to suggest the number of Canadian officers working in SWAT teams has remained largely stable since Alvaro examined data from the late 1990s for a similar study, despite an uptick in calls.

“I think it’s great that we have a discussion. I’m a little bit concerned about Canadian-izing an American problem,” he said.

Jeffrey Ian Ross, a criminologist at the University of Baltimore, has done extensive research on Canadian and American criminal-justice systems. He said Americans have far more access to data and more robust debate about how their police operate.

For example, the U.S. government’s Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics database details large police forces by budget, officer demographics and specialized units like SWAT or tactical teams.

Ross said Americans might also be more interested in SWAT units because they already account for more visible calls and budget than Canadian forces.

“Citizens and their representatives are worried about the use of these tactical units for a variety of reasons, from the civil-liberties issues… to spending.”

Lutz said the WPS intentionally labels the unit the Tactical Support Team, because it plays a supporting role to regular police and units like the drug or bomb squads.

He said having the team respond to low-risk calls prevents them from constantly feeling in a high-adrenaline environment, so they can better assess risks.

“It does keep our members sort of grounded and balanced. Part of that is we do a lot of community relations; (we) reach out, speak to the public, meet with the kids, that sort of thing,” Lutz said.

“The media and movies sensationalize everything to the nth degree,” he said. “Like all our police members, our tactical-team are members of the community here, too.”

But Roziere said that approach could backfire. American studies by Kraska show tactical units hold elite status within police forces, and that regular officers see them as role models for how to go about policing.

“It, in fact, can do the opposite, and encourage street-level officers to adopt a potentially more aggressive approach when they respond to those same types of calls.”

● ● ●

The Winnipeg researchers said they’re most concerned by the high number of mental health calls that SWAT teams are assigned, though they cautioned the data seems unreliable.

According to the data, TST logged less than 20 suicide threats and well-being checks in 2013, and nearly 3,000 of them in 2016. He said some would explain a SWAT-team response, such as when someone is brandishing a weapon, but others seem more minor.

Lutz said supervisors choose whether to send a regular or tactical officer to a mental health crisis, and that officers weigh the risks when they arrive, in terms of how much equipment they carry and how they communicate.

“We weigh these situations as they come in, and we evaluate our response when we look at the details,” Lutz said. “Sometimes these incidents have escalated since a (911) call was made. So they just generally approach them with due caution all the time, and evaluate when they get there.”

He said officers always try to de-escalate tense scenarios, and are quick to call the crisis-negotiation unit when someone’s in imminent danger.

“We’re in the business of helping people, and we just try to do that as safely as we can.”

But groups helping with mental-health training for Winnipeg police worry the officers need more hands-on instruction.

“It takes patience; it takes time,” said Chris Summerville, executive director of the Manitoba Schizophrenia Society.

He’s spent a decade training police officers about mental health, most recently with role-playing exercises in Winnipeg.

While he lauds the police for taking on the initiative to train all its 1,450 officers, he said the training amounts to just an hour.

“It’s not that I am upset with the Winnipeg Police Service, I’m concerned about the effectiveness and thoroughness of the training.”

But WPS says that’s only one part of officers’ mental-health training, which is integrated into general instruction on vehicle and taser use, safety as well as communication. “As well, recruits receive over 16 hours of dedicated mental health training,” wrote Const. Jay Murray. Summerville said the hardest part is reversing the very reflexes police officers use to do their job.

“Typically, you’re more authoritarian, more demanding, more able to control,” he said. “Officers have a very, very difficult time moving from the tactical mindset and training to the mental-health position.”

For example, standing with legs apart and hands on hips and maintaining piercing eye contact can help subdue a criminal, but escalate someone with paranoia. Voices from a walkie-talkie can confuse someone with schizophrenia. People in deep confusion need police to continually repeat instructions, without them taking on a hostile tone.

Summerville says those reflexes are likely even more pronounced among tactical officers, and that even the black or camouflage uniforms they wear can agitate someone in a fragile mental state.

“The more military gear you have on you, the potential is more of a negative situation.”

Tara Brousseau Snider, head of the Mood Disorders Association of Manitoba, said officers need to know how to communicate with people in distress, and not assume that everyone’s violent.

She said officers must protect themselves, but that often times an agitated person will calm down if their emotions are being acknowledged.

“They need to be able to talk to the individual,” she said. “As soon as make that connection, that’s where you see the escalation: empathy, compassion is what helps when someone is in crisis, stressful as it may be.”

Summerville said the most effective thing for police officers is to meet people who have had suicidal ideation, bouts of depression or eating disorders.

He worries that the most violent cases reported by media could influence the decision on whether to send a tactical team to a person in distress.

“We know people’s perceptions of people with mental illness are laden with myths. And just because you’re a police officer doesn’t mean you don’t bring some of those myths with you.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Saturday, January 13, 2018 9:06 AM CST: Updates headline

Updated on Thursday, January 18, 2018 4:09 PM CST: This article has been updated to reflect that WPS recruits receive 16 hours of mental-health training; this article previously implied that the trianing only amounted to officers' one-hour of roleplaying scenarios.