Right place, right time, one career-defining photo

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/01/2018 (2295 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

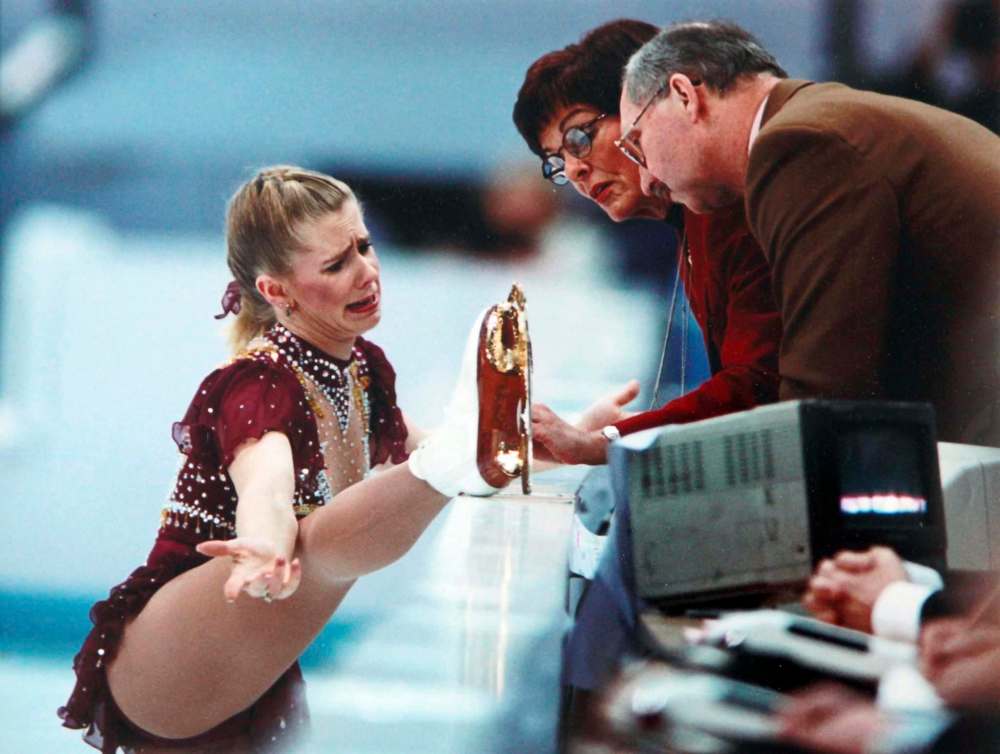

As soon as Tonya Harding put her leg up on the boards to show the judges her broken skate lace at the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, it became an iconic moment in sports history. Here was the beleaguered U.S. figure skater — the talk of the American tabloids and the centre of one of the biggest scandals in figure skating history — essentially asking for a do-over. At the Olympics.

Twenty-four years later, that scene is playing out in movie theatres all over North America, in the much buzzed-about biopic I, Tonya. But the cameras that were actually there immortalized it.

The photographer behind one of the clearest, most precise shots of that moment is none other than the Free Press’s own Boris Minkevich.

Minkevich, 47, was not the Free Press’s own at the time. He was 24 years old, the same age as Harding, and had just gotten out of college.

“I had arranged to have accreditation for the Olympics through the Canadian University Press,” he recalls. “I had to find all these different clients to pay for my trip, and finding different people to work for because I wasn’t on staff anywhere.”

It was his first Olympic games. “For a young student, this was the big time,” he says. “This was the actual chance to be with all those (photographers) you saw in magazines.”

In Lillehammer, Minkevich noticed that the European and Asian photographers weren’t initially as interested in Harding as the North American photographers.

“This was the big story in North America: Tonya Harding and Nancy Kerrigan. It was a big U.S. soap opera. Every time she’d skate, it’d be packed with U.S. photographers,” he says.

“It wasn’t really until she broke her skate lace that it really went bananas.”

Minkevich recalls that moment vividly. “She comes on to skate and she’s doing her routine — and then she stops skating and there was silence,” he recalls.

“An incredible, unbelievable pause. I remember it — like, it was silent. No one was taking pictures. Everyone was confused, almost. And then, as soon as she went over to the judges to show why she stopped and she was crying and all that stuff, that’s when the sound of shutters drowned out everything.”

Photographers were assigned certain positions along the boards. “I was lucky, because to my right, facing the boards, there was a Reuters photographer from Japan, a very short guy.”

Minkevich, meanwhile, is six-foot-seven.

“I swung over the big lens, and it literally swung over this other photographer’s head, and I had a perfectly clear view of that angle,” he says. “All I thought in my head was, ‘When am I going to run out of film?’ We were still in the film days, so you had 36 shots. You just buzzed through the film hoping you wouldn’t hear the sound of the film starting to rewind just as the moment was happening.”“She stops skating and there was silence. An incredible, unbelievable pause. I remember it– like, it was silent. No one was taking pictures. Everyone was confused, almost.”

Minkevich had The Shot, now he had to figure out how to actually get it out there. He’d met a guy from a photo agency in Paris, which processed the photo and distributed it.

“I don’t even know where it ran,” he says.

Shortly after Minkevich was hired by the Free Press, he went to Washington, D.C., to accept an award. He had entered his photo in a National Press Photographers Association contest.

“I got third place in the world for Sports Feature,” he says. “Just some kid from the Prairies who figured out how to get to the biggest sporting event in the world.”

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti

Columnist

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.